A yellow bus has been the universal sign of school for decades. Although the actual colour of the bus may not change, the tire tracks left behind may soon be green if a new Ecology Ottawa push for electric school buses is successful.

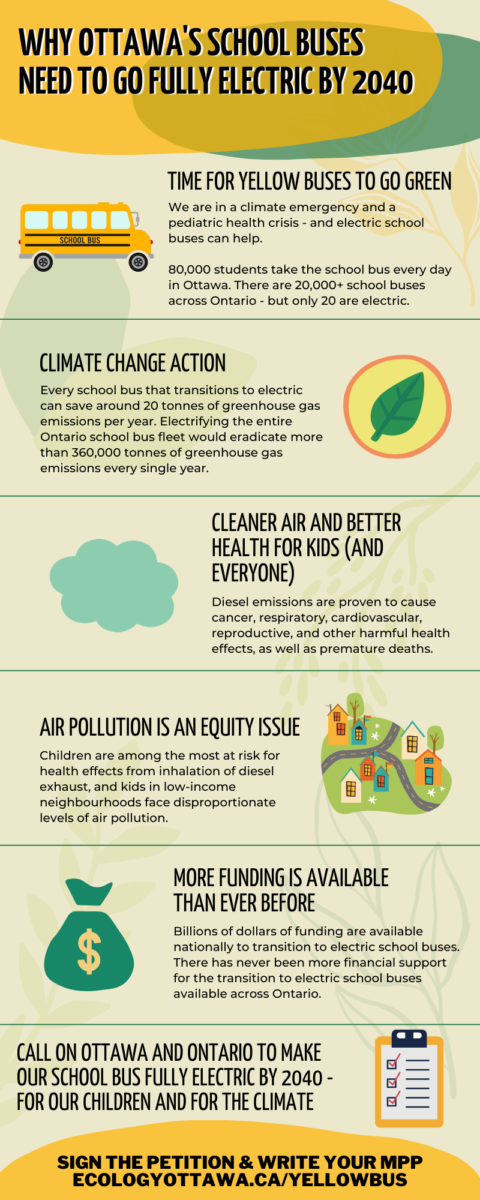

The group is one of many Canadian environmental organizations campaigning for an electric school bus fleet. The advocates argue that, not only are traditional diesel-powered buses harmful to the environment, they are also associated with significant health risks.

Ecology Ottawa is pushing for change through its Breathe Easy and Electric School Buses campaigns.

‘We have to introduce electric school buses so we’re not having kids breathe diesel in their schoolyards. It’s imperative that we start moving very rapidly.’

— Steve McCauley, senior director of transportation, Pollution Probe

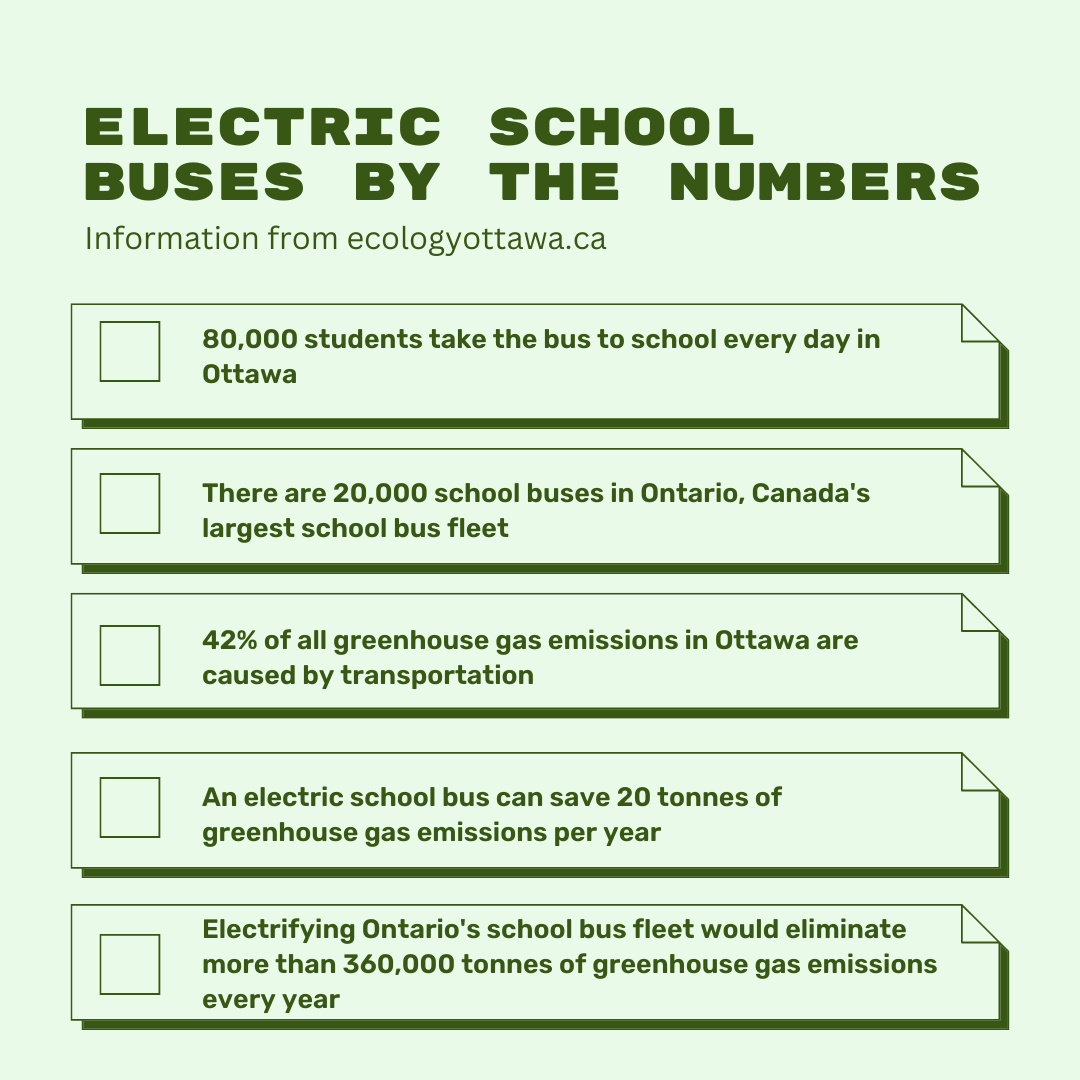

Breathe Easy monitored 46 locations across Ottawa in 2021 to examine air quality. The results found that lower-income neighbourhoods were subject to elevated levels of contaminants and environmental health risks.

Cheryl Randall, the climate change campaign organizer at Ecology Ottawa, said children are at high risk for respiratory infections because their immune systems are not fully developed. Children in low-income neighbourhoods are particularly vulnerable. Randall is heading up the electric bus campaign for Ecology Ottawa.

The campaign says “diesel emissions are proven to cause cancer, as well as respiratory, cardiovascular, reproductive and other harmful effects.”

There are 80,000 students in Ottawa who take the bus to and from school every day, including Sarah Charron’s two young children.

Charron is also a member of For Our Kids, a national network of parent-led, community-based grassroots groups involved in climate action.

She said she joined the group about a year ago because she wanted to do more about climate change.

“It’s important for me to feel like I’m taking part and fighting to make change,” said Charron, adding she wants to create change that will affect everyone’s lives, not just her children’s.

Charron has been a part of groups that have urged the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board and transit authorities to do more to green bus fleets. There is a general consensus on the need for electric buses, but a big obstacle is funding.

Randall acknowledges the issue, but said the federal Zero Emission Transit Fund (ZETF) will cover 50 per cent of all costs to electrify the school bus fleet. Through ZETF, the Government of Canada is investing $2.75 billion over five years, starting in 2021.

This funding will help support public transit and school bus operators’ plan for electrification, back the purchase of 5,000 zero-emissions buses and help build infrastructure such as charging stations.

However, the rest of the funding is still in question. Randall said the average cost of a diesel bus is $125,000, while an electric bus is about $345,000. While the up-front cost of an electric bus is significantly higher, over the lifetime of a bus — typically about 10-12 years — the energy and maintenance costs are lower, eventually resulting in an overall saving.

Still, the upfront cost of an electric bus is a big pill to swallow for a private operator, considering most bus operator contracts extend over five to seven years, said Randall. If, she added, contracts could 10 to 12 years, the opportunity to go electric and eventually save is far more appealing for a bus operator.

Prince Edward Island has already turned 25 per cent of its school buses electric. This is something Steve McCauley, senior director of transportation for Pollution Probe, sees as model to follow.

“We see opportunities for Ontario’s economy to increase the workforce and have more ‘green’ jobs,” said McCauley. “We’re seeing a lot of excitement around the opportunity.”

Pollution Probe was Canada’s first environmental group, starting in 1969 at the University of Toronto. The non-profit organization is focused on de-carbonizing transportation.

A Pollution Probe report in May outlined the opportunities available to accelerate school bus electrification in Ontario.

Most of Ontario’s 20,000 school buses will require replacement before 2030, making now the ideal time to start the transition. But if existing buses are replaced with another generation of diesel buses, this will “lock-in another 12 years of deleterious health impacts for our children, avoidable greenhouse gases for our climate, and missed opportunities for Ontario’s economy,” the report notes.

“We have to introduce electric school buses so we’re not having kids breathe diesel in their schoolyards,” said McCauley. “It’s imperative that we start moving very rapidly.”

Outside cost, the electrification of buses in Ontario seems to be heading in the right direction. Earlier this year, an agreement was reached to electrify the full OC Transpo fleet by 2036.

Technology is continuing to develop as more electric vehicles hit the streets. Companies such as Ford, GM, and Hyundai have entered the electric vehicle arena and are increasing production rapidly.

Although it’s difficult to put a timeline on the project while funding is still in question, Randall said she is hopeful local schools will have all electric buses across Ottawa by 2040. But the Ontario government will have to step up to move the campaign along, said Randall.

“It’s achievable if the right steps are put in place.”