By Cindy Lam Hoang

After a long day of fun at the park, kids and adults may all have the same need: to go to the washroom.

However, this basic need may not even be accessible, as most parks and public spaces in Ottawa do not have public washrooms. This may be an inconvenience for some, but it is an immediate problem for those with visible or invisible disabilities.

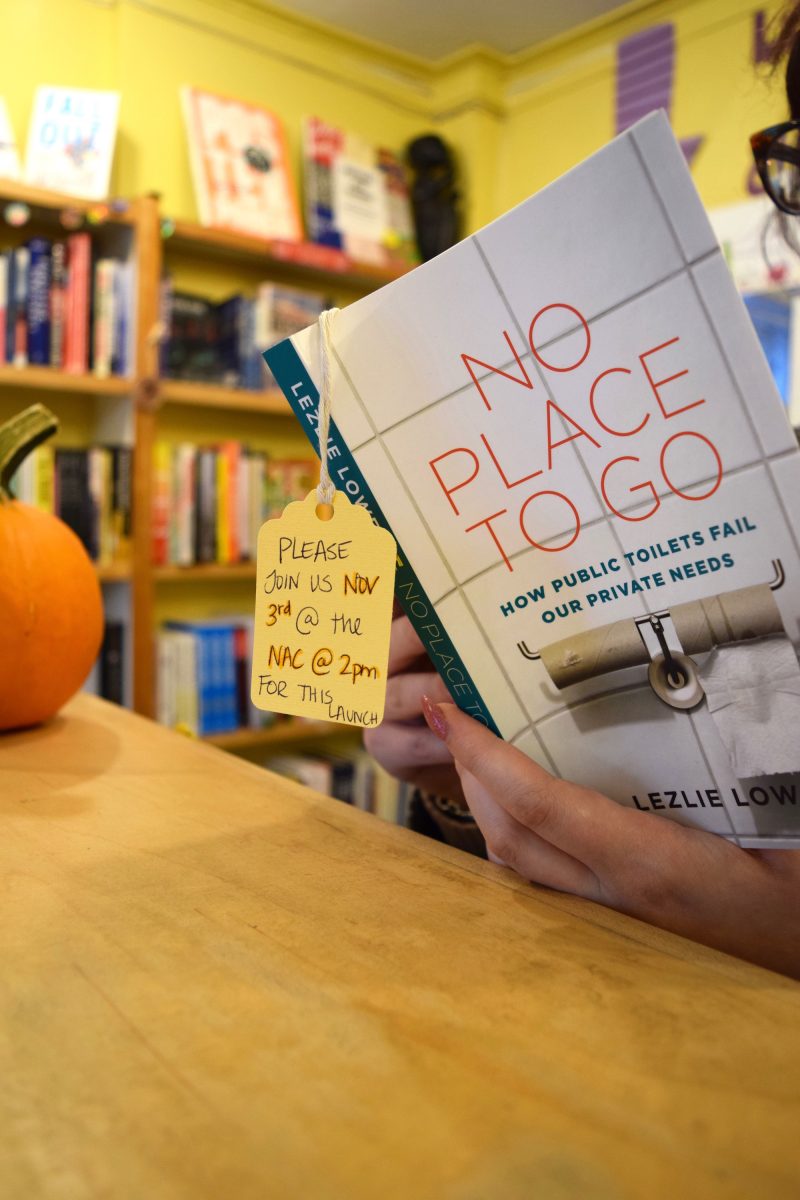

Journalist and author Lezlie Lowe addresses the topic of washroom accessibility and politics concerning public toilets in her first book, No Place to Go: How Public Toilets Fail Our Private Needs.

“The book is about access, and in that examination, it’s about use of the city,” said the Halifax, N.S. based author. “So, how much or little do different groups of people, based on their bathroom needs, have equal access.”

Lowe said that there are many factors that decide whether one has equal access to public bathrooms including gender, ethnicity, mobility, health, socio-economic status and appearance.

These factors can make one privileged in terms of being able to use public washrooms without facing the discrimination that confronts those with disabilities, who are transgender, or who are homeless.

“I’m a woman, which is the one point where I’m very unprivileged when it comes to the bathroom,” said Lowe.

Lowe said in her personal experience, in her research for the book, and in her interviews with people, the lineup for the women’s washroom is always longer than the men’s line.

Lowe said this is due to many factors such as having to use a stall, menstruation, care-taking needs. Women generally require more time in the washroom and public washrooms do not reflect that need.

Related story: Raising a stink about public washrooms in Ottawa: Why you should care about toilet privilege

“Where you can fit three stalls in the women’s [washroom], you can fit two stalls and six urinals in the men’s [washroom].”

Lowe explored more issues of accessibility at a recent appearance in Ottawa at the National Arts Centre, which she hosted with Joan Kuyek of the GottaGo! Campaign Ottawa.

The GottaGo! Campaign Ottawa seeks equal, accessible, and safe washrooms.

The five-year-old organization has been busy bringing the issue of accessible public washrooms to the fore by, for example, putting up signs around the city to point out public washrooms which can be difficult to find. They also funded an accessible portable toilet at the Harrold Place Park splash pad in Carlington two years ago until the city took responsibility for it.

One of their most recent successes was working with the city to have washrooms put in Light Rail Transit stations.

“[The city] was only going to put washrooms in the terminus stations because that’s required by Ontario law,” said Kuyek.

In collaboration with Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, GottaGo! started a petition, spoke to city councillors and lobbied until the city agreed to put washrooms in every station with a transfer.

“Although it’s so obvious, it’s hard to imagine [we] had to organize it to get [it] done.”

While having washrooms at the stations is convenient, it is a necessity for those with invisible disabilities, such as Crohn’s disease or Colitis.

“The way it impacts someone with the disease is that you have to go many times a day, and it really keeps people inside their homes because they want to avoid the situation,” said Sherry Pang of Crohn’s and Colitis Canada.

Although there have been successes in the city providing accessible public washrooms, there are still problems.

Karen Scott came face to face with an accessibility problem during a recent visit to a restaurant .

Scott, who is in a wheelchair, had called a restaurant to ask if their bathroom was wheelchair accessible. She was told yes. Scott dined at the restaurant with her family, only to discover that the bathroom stalls were two inches narrower than her chair.

“I think it would help if able-bodied people also complained, so it’s not just my voice saying there’s an issue,” said Scott. “[Because] it sends me the message, constantly, that ‘you don’t matter.’”

Lowe agrees. She says one of the first steps to creating accessible washrooms for all is to start having conversations to address the problem.

[…] Related Stories: You go, I go, we all go: toilet talk with Lezlie Lowe […]