Cassandra Trimnell is no stranger to blood transfusions — the needles, the nurses and the beeps of medical machinery are nothing new to her. In fact, a blood transfusion is a regular part of the 35-year-old’s life.

“On multiple occasions, not just one, I have been saved by a blood donation,” Trimnell said. “(When) I was planning my 30th birthday or I wanted to travel somewhere out of the country, I got a donation so I could be able to do that.”

Trimnell has sickle cell anemia, a blood disorder that inhibits red blood cells from carrying oxygen and travelling through blood vessels. To increase public understanding of the condition, she founded Sickle Cell 101 in 2013.

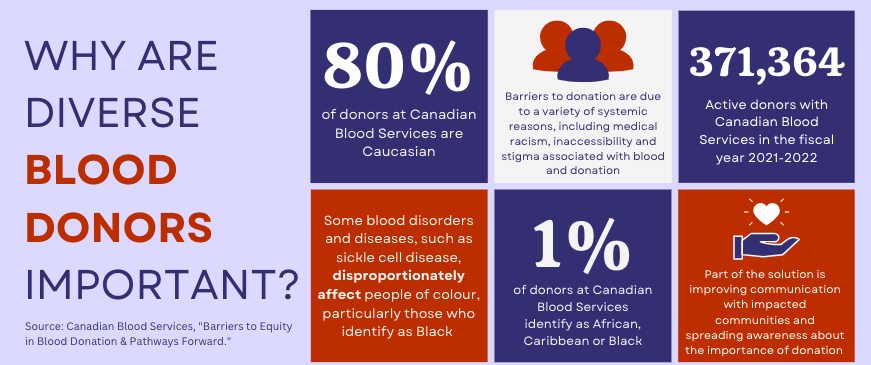

Trimnell said one of the most important areas of education is sickle cell anemia’s disproportionate impact on people of colour, particularly those from Black communities. The disparity has prompted many blood disease experts and patients to bring awareness to the need for an ethnically diverse blood supply and for stem cell donors in Canada.

“Blood donations are important because of the state of our blood. We don’t have ‘healthy blood,’ or our bodies don’t produce that,” said Trimnell, who also works as a patient advocate. “So many of us rely on donor blood that would be considered ‘healthy’ blood to carry out the function of blood for us.”

In the U.S., sickle cell disease occurs in about one of every 365 Black or African American births compared to one out of every 100,000 Caucasian births, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In Canada, sickle cell disease affects at least 5,000 individuals, according to the Canadian Paediatric Society. While the racial profile of Canadians affected by the disease is unknown, the Sickle Cell Awareness Group of Ontario says a “significant percentage” of Ontarians of African descent may carry the sickle cell gene, and in some cases the carrying rate may be as high as 25 per cent.

According to Canadian Blood Services, sickle cell disease patients are often treated using blood transfusions that need to be a closer match beyond the general type A, B and O blood groups. Red blood cells have proteins on their surface called antigens, and the non-profit said there are hundreds of unique combinations of antigens — phenotypes — that could be matched between donors and patients of the same race or ethnicity.

The need for phenotype matches in donation was a major theme of this year’s Ontario Sickle Cell Summit. Dr. Tanya Petraszko, a senior medical director for Canadian Blood Services, said during the online summit that because red blood cell antigens differ between racial groups, it’s important to have representation from diverse communities in the blood donation system.

“To meet the needs of patients with sickle cell disease, we need more donors with the same blood types,” Petraszko told participants in the summit session titled Barriers to Equity in Blood Donation & Pathways. “Red cell antigens are inherited — that’s why we look to the communities where our patients come from.”

Petraszko said 80 per cent of CBS donors identify as Caucasian so it can be difficult to find blood donation matches with a high chance of success for some sickle cell patients. She added that there are several challenges that contribute to the imbalance of blood donors.

“(There are) a lot of barriers — personal, socio-cultural, systemic, organizational,” Petraszko said, referencing a study presented at the Canadian Society for Transfusion Medicine in 2021. She said some examples of barriers to blood donation can include racism and mistrust of the health system, cultural ideas of blood and donation, as well as eligible screening criteria that could deter potential donors.

Diversification and equity are also crucial for stem cell transplantation, the only known cure for sickle cell disease. Stem cells come from bone marrow or umbilical cords and can develop into red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets. Similar to blood donation, finding a stem cell match is key.

“Diversity in our stem cell donors is a huge priority for Canadian Blood Services,” said Petraszko. “We’ve identified five racialized groups that we really need to increase the representation of in our cord blood bank and stem cell registries, and a Black, African and Caribbean groups are one of them.”

Stem cells are matched using the human leukocyte antigen system, which is a protein signature in human blood, said Dr. Matthew Seftel, a medical officer for Canadian Blood Services. He says there is only about a one in four chance that a patient with a blood disease can find a stem cell match within their family, meaning that “diversity is incredibly important” in stem cell registries, especially for those in ethnic communities disproportionately impacted by certain blood diseases.

“Just by virtue of variation in population genetics … in the same way that there are infinite numbers of hand signatures of humans in the world, small variations in HLA signatures become quite important for a recipient patient in need,” explained Seftel. “Beyond numbers, what’s also important is ethnicity.”

“If we were to have a registry that is predominantly or solely consisting of those of Caucasian heritage, we would therefore have a more restricted set of HLA signatures,” Seftel said. “We would not be able to address the needs of those with different HLA types, including and especially those of non-Caucasian ancestry or those of mixed ancestry.”

Seftel said that, while everyone is encouraged to register for blood and stem cell donation, those from non-Caucasian groups are “very, very welcomed” to register to help patients from non-Caucasian groups get transfusions and transplants for diseases like sickle cell. He added that registering to become a blood and stem cell donor is “easy and safe” and can be done on the Canadian Blood Services website.

For someone like Cassandra Trimnell, who now uses her lived experience as a sickle cell patient to spread awareness, registering to donate is not only simple, but potentially life changing.

“You’re improving the quality of life of somebody. … So many people are very, very reliant on blood,” said Trimnell. “Not only is (donation) saving people’s lives, but it’s enhancing people’s lives so that they can live a fuller life, or for people living with chronic illnesses or blood disorders like sickle cell.”