A Canadian coalition of women’s health advocacy groups has struck a partnership with TD Bank Group to improve maternal health, fetal monitoring and cervical cancer screening among “underserved” patient populations in B.C. and Alberta.

The two-year collaboration — announced in October by the Women’s Health Collective Canada, Alberta Women’s Health Foundation and B.C. Women’s Health Foundation — “will impact the lives of thousands of women and children,” the organizations say.

The new program is part of the growing push to overcome systemic bias in Canadian health care that has often left women marginalized in medical research and treatment, and poorly served by health professionals.

And it’s not just a Canadian phenomenon. Medical professionals in the U.S. are more likely to dismiss women as too sensitive, hysterical or as time-wasters, according to a 2018 study published by the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Robin Mason, a scientist at the Research Institute at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto — which has a long history of addressing women’s health using a holistic and patient-centred approach — said the disconnect between women’s needs and traditional medical services can be traced to fundamental inequities in the system.

“I think that there’s just been a lack of understanding of women and their bodies and their needs because so much of the work has been developed around the male model,” said Mason.

“The American federal drug agency, when it did a study (in 2001), found that eight out of 10 drugs that had to be withdrawn from the market were withdrawn because of negative impacts or effects on women. It cost billions of dollars to develop a drug and bring it to market and then to have it withdrawn because they didn’t test it on women.”

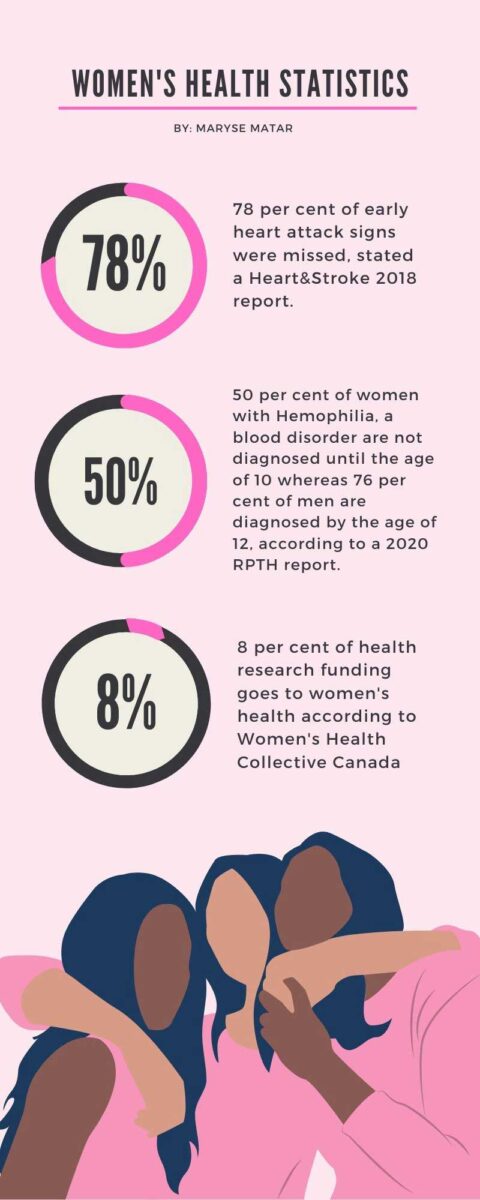

In health research, only eight per cent of funding is dedicated to women’s health, according to the Women’s Health Collective Canada.

“Women make up more than half the population of Canada, and yet the picture of our health remains incomplete,” the WHCC says on its website. “Due to a legacy of inequity in the healthcare process, women’s unique health needs continue to be misdiagnosed, misrepresented and misunderstood.”

According to Mason, the WHCC has been doing studies involving women with diabetes that illuminate the gender bias in the system.

“The younger women, as well as the older women, actually felt like their health-care providers didn’t take them seriously, didn’t answer … the questions that they wanted answered, were a bit patronizing about their experiences or just discrediting their experience,” she said.

Mason said part of the problem is the range of social myths about women being too emotional or irrational, or that they don’t handle pain well.

“I think that there’s a whole series of beliefs that have been socially created and socially endorsed that contributes to some of that gender bias,” she said. “Without a doubt, we know that there’s racism. And we know that there is bias — body weight and body type biases — and that these are socially constructed, which means that they don’t exist everywhere in the same way. So in our context, there are for sure these types of stereotypes and biases that are harmful and hurtful.”

When women are told to ‘just lose weight‘

Eesha Affan, a fourth-year Carleton University student, was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2019.

Affan faced a few complications during her diagnosis and says she was often dismissed by her health-care providers.

“I went to my family doctor in like 2018-2019 because my neck kept swelling up,” she said. “We had no idea why it was happening.”

Affan explained that, she says her doctor was “just super dismissive. She (said) you have a history of thyroid issues in your family and that’s just something South Asian women go through,” explained Affan.

On an occasion when her doctor wasn’t available, Affan went to a different doctor.

“I saw somebody else, and they referred me to a specialist who then diagnosed my cancer. So my family doctor is kind of useless. I don’t know if that was a race thing or if that was a female thing. She did not take that very seriously at all,” said Affan.

“The cancer had progressed outside of my thyroid by the time they actually found it,” said Affan.

“Women make up more than half the population of Canada, and yet the picture of our health remains incomplete. Due to a legacy of inequity in the healthcare process, women’s unique health needs continue to be misdiagnosed, misrepresented and misunderstood.”

— Women’s Health Collective Canada

The problems with providers persisted, she says. In one instance after her diagnosis, Affan said she was told to try to lose weight.

“Well, no,” she recalls saying. “I’m not getting swelling in my neck because of weight issues. So there was a lot of that also, because thyroid issues can cause excessive weight gain and excessive weight loss.

She says she was often advised to eat healthier and exercise more.

However, before her thyroidectomy, the surgeon informed Affan that her hormones had been out of balance for at least five years.

After surgery, Affan was given a low dose of pain medication.

“I was in constant pain for a month after surgery, especially in the week right after when I was in the hospital,” she said.

She was told by medical professionals that she could not receive a higher dose of pain medication.

“When I came home from the hospital, they literally gave me six tablets of pain medication,” said Affan. “My dad had dental surgery two weeks after that and got prescribed the same pain meds and got more than I got after having my neck sliced open.”

Because of these negative experiences, Affan said she has become skeptical of the health-care system.

“Back in 2019, I went in being like, ‘Trust the doctors — they know more.’ But coming out of it, I’m definitely more skeptical of doctors and how they treat you,” she said. “I advocate and speak up for myself a little bit more now in terms of health care. It’s really disappointing to not just be able to trust my healthcare providers. I really have to be on top of it myself.”

Affan advised other women to speak up for themselves, too.

“You definitely know your own body best,” she said. “You know what’s going on with yourself better than anyone, including any doctor. So if you think something is wrong, push to get help with it.”

She added: “It can be hard, obviously, when people are ignoring you or telling you that it’s not an issue. See multiple doctors, you can get second opinions. If you feel like something’s wrong with your body, keep pushing until you find out what it is.”

Feeling neglected because of race and gender

Hannah is a 22-year-old student. She shared her experience receiving healthcare services as a Black woman with Capital Current. Her last name has been withheld to protect her privacy.

She described feeling neglected at times because of her gender and race.

When Hannah was 18, she was experiencing pregnancy symptoms and needed to get a test. However, she did not trust her family doctor as he was rarely available.

“At least five of 10 times — like 50 per cent of the times that we (tried) to book appointments — he’s on vacation,” she said.

After providing a urine sample to a medical lab, Hannah received complicated medical forms meant to clarify whether she was pregnant or not. Looking for guidance and understanding, she went to her family doctor’s clinic.

“I asked to speak with my family doctor … and the family doctor was on vacation,” she recalled.

Instead, Hannah looked for help at a walk-in clinic.

“I had the forms with me. I just said I need someone to tell me what exactly is happening. And then that’s when I got my answer,” she said. She was pregnant.

“I had such a bad experience on that day,” she said. “That was traumatic for me. I wasn’t even fond of going for checkups or anything like that with my family doctor.”

Hannah had an abortion. Not long after the procedure, she decided to get an intrauterine device — an IUD.

Within a year, Hannah was back at her family doctor’s office for a checkup.

“I went in and the receptionist had never filed my file. When I went there to ask for all the information, I gave her the (forms), I gave her a copy,” she said. “(The doctor) didn’t know about any of that. He mistook my file for my sister’s file. I told him that I was not my sister, but then he was still reading through (her) file and he didn’t have my file with him.”

In July 2021, Hannah had an emergency at work and required a doctor’s note stating why her performance was being affected and if she could start working from home. She had prepared a list of all her symptoms such as disruptions in her menstrual cycle and how her health was being physically affected, suspecting she was having IUD complications.

“I gave him all the dates that affected me most and his answer was, ‘I never see you. I don’t have data to explain any of these symptoms.’ My reply was that you’re most of the time on vacation, so I can’t actually book an appointment with you,” she said. “I even told them if you can’t do anything about this, can you refer me to a gynecologist — and he had no referral.”

Hannah explained to her doctor that she got the contraceptive inserted after she had had an abortion in November 2018.

“After I said that, he looked at me and he stopped talking,” said Hannah. “He said you should have been going to work . . . (He said) your best bet is going back to the place that inserted your IUD to remove it. And he wrote a letter, just so that they could remove my IUD … That’s not what I actually wanted.”

At that moment, Hannah felt like gender and race played a factor in the services she had received.

“In African culture as well as Black-Caribbean cultures, abortions are taboo. … When I mentioned the fact that I had an abortion … there was no solution from there. I left the clinic having to explain to my boss with my own words (why) my doctor can’t really provide me a note. I’m at the risk of losing my job,” she said. “I was judged for the actions that I took. In terms of my race, and culturally as well. It was also very cultural for him to not say anything after I explained the abortion because as soon as I mentioned it the service went from horrible to none … I felt helpless because if I was male, if I was maybe with my partner, would he have given me different service? If I was maybe with my dad, would he have given me different service?”

Hannah advised women seeking medical advice or treatment to do their research.

“Even though finding a family doctor in Ottawa may be a difficult process, don’t worry, but make sure your family doctor is equipped for your family long term, for however long it is. Do your research on how they operate their clinic,” she said.

Doubted by your doctor

Twenty-three-year-old Sarah, whose last name was withheld for privacy reasons, shared several experiences where she felt neglected by health care professionals.

A few years ago, Sarah had what she described as a horrible experience with her family health-care provider.

“I was having post-concussion symptoms. I was asking her if there’s any medication I can take or is there a specialist who can be seen because, at this point, I can’t be going to school. My life (was) literally falling apart,” said Sarah. “She (asked), ‘Are you sure you’re not pregnant?’ I was, like: That has nothing to do with me getting headaches.”

Sarah left the doctor’s office with her problems unresolved. She had to do her own research to try to find a specialist.

She recalled another incident in which she injured her knee.

“I did something to my knee and I go in because, at this point, I can’t really walk. It’s been four or five days and I’m still in pain,” said Sarah.

When she went in to get the knee checked she says she felt dismissed by her doctor.

“She didn’t even look at the knee. She (said), ‘Just take some Advil and you should be fine.’ At that point, I was, like: ‘I waited three hours to see you. You didn’t even touch the knee, see if I could walk or bend it.’ I ended up going into a walk-in clinic that night because I couldn’t walk,” said Sarah.

At the clinic, another doctor examined Sarah’s knee.

“He touched my knee, (and said), ‘It was really hot. It’s very inflamed. You need to be icing it, you need to be taking medication.’ He sent me for an X-ray and I found out that I tore my meniscus,” she said.

“So it was actually serious. If I just followed her (family doctor’s) advice, it could have gotten worse.”

At a separate appointment, Sarah went to see her family doctor and was asked once again if she was pregnant.

“I was just really sick. I guess it was because of stress,” she recalled. “I was feeling very nauseous and (the doctor said) should we just do a pregnancy test? Maybe it’s just morning sickness. (I said) no, I’m a virgin.”

Despite Sarah clarifying that she could not have possibly been pregnant, the provider continued to question her about a pregnancy, Sarah says.

“She didn’t even check my heart rate or anything. I (had) to go to the hospital and a week later, it turned out that I had a cyst on my ovaries,” said Sarah.

Like Hannah, Sarah encouraged women to persist in finding a doctor they’re comfortable with.

“Find someone that maybe you identify with. Maybe finding a doctor that is the same gender — same race might help, as well,” she said.

In the future, Sarah said, she hopes that the health-care system becomes more accommodating and easily accessible.

“I would hope the health-care system, especially in Canada, becomes more diverse and allows doctors from other countries to come practice here and just have more availability and better service,” she said.

Dismissive doctors are

Lilo Noort, a fourth-year Carleton University student also recalls being dismissed by her health-care providers.

“I honestly have never really felt like I was acknowledged by any doctor I’ve ever had. Whenever I was sick, they’d be like, ‘Oh, it’s probably just anxiety, it’s probably just nothing,” she said.

Noort explained her negative experiences at one clinic.

“I had a really bad fever, sore throat, I could barely swallow, I couldn’t stand up for longer than 10 minutes,” she recalled. “Something was really, really wrong… They did a bunch of different tests and then everything came back negative,” she said.

When she spoke to the doctor, Noort was questioned about her social life and sexual activity. She explained that she had not been partying or having sexual relations.

According to Noort, the doctors disregarded her answer.

“(The doctor) said, ‘Well, I think you are so you should probably just stop that,’ ” said Noort. “I was just completely blown away that a medical professional would say something like that to me and completely disregard my symptoms. She refused to do any other testing because — I don’t know —preconceived notions about me because of my age, because of my gender, because of the way I looked.”

Noort stated this wasn’t the only time she’d had a negative experience that clinic.

“I found it was just straight up rude and kind of dismissive and shaming me for being sick or for what led up to me being sick, which was really unfortunate,” she said. “Ever since then, I haven’t really ever gone back … I have either contacted Telehealth, or I started seeing a naturopathic doctor.”

Noort described another experience where she had to go to an emergency room after experiencing a small seizure last year.

“The doctor that saw me (said), ‘You just need to stop stressing out so much . . . You’re clearly stretched too thin.’ But, at the time … I was not stressed out by any means,” she said.

“The whole thing could have been avoided if they had acknowledged me. I’m not a scientist, I’m not a doctor. But I think that you know when something is wrong with your body.”

— Lilo Noort, student

Noort went home to Toronto and saw her primary care doctor for a second opinion.

“More tests were done. It eventually got solved, but the whole thing could have been avoided if they had acknowledged me,” she said. “I’m not a scientist, I’m not a doctor. But I think that you know when something is wrong with your body.”

Noort advised other women to push back when not receiving adequate care.

“It’s OK to not feel 100 per cent, and that if you’re not getting the adequate help that you need, going down multiple different avenues is OK. Your problems matter, and what you’re going through is important even if you seem crazy,” she said.

When women are neglected due to their gender, race or body type, Noort says, it’s a systemic problem in the health-care system.

“It doesn’t fall on the individual, it falls on the health care system. Dismissive language is not OK. I think that the Canadian health-care system definitely is biased,” said Noort. “I know that there is a lack of healthcare professionals, and that might even tie into the fact that in Canada, we don’t recognize a lot of different countries’ (medical) degrees. But if you think about it, it’s a policy rooted in racism.”

Being told ‘it’s just period cramps’

Emily, 19, shared a particularly troubling incident.

“I was put on birth control by my request. One day, I got very, very sick. I started passing out from the pain,” she explained. “I was bleeding from my vagina, but I wasn’t on my period. I never felt cramping that bad. After calling Telehealth, they told me that I should go to the ER immediately.”

At midnight, Emily arrived at the emergency room.

“They were looking to see if maybe I was pregnant and had a miscarriage. They’re looking to see for stab wounds because they were really concerned by the amount of blood that was coming up. But they found no answers,” she said.

Emily sat in a private room for hours with no answers.

“I went up to the front desk, and I (said) it is like three in the morning. What’s going on? They kind of just yelled at me,” she said. “Keep in mind, I was in a lot of pain, very dazed. When you lose that much blood, you’re going to be out of it. I just remember them snapping and yelling at me.”

After waiting for many more hours, Emily was sent home and advised to take Tylenol.

“The morning after I got home from the ER, I did pass out in the shower and hit my head, which could have caused, in theory, a fatal injury — especially since I was completely home alone,” Emily explained.

After receiving no helpful advice from doctors, Emily decided to stop taking her birth control medication to see if it would make a difference.

“Turns out … it was my birth control that was trying to kill me. The doctor’s recommendation after I told them that was just: ‘You can stay on that same birth control, though, you’ll probably be fine.’ I obviously did not take the doctor’s advice,” she said.

According to Emily, she had to argue with her doctors for them to let her switch birth control prescription.

“It was not only emergency care, but also my general practitioner that was telling me, ‘You’re fine. You’re over-reacting. Are you sure it’s not just period cramps?’ ” said Emily.

“I definitely do feel like I was discriminated against because of my gender. They didn’t take my pain seriously,” she said. “I felt very dismissed, very ignored, especially because the hospital was empty. There was no reason for them to be so dismissive.”

Emily also received a negative reaction when she asked for a female nurse.

“I was seen as dramatic because male nurses repeatedly just kept asking me if I was certain it wasn’t a period,” she said. “I wish I could have stood up for myself a little more because I didn’t push. But I was so tired and so drained at the end.”

Advocating for yourself

Although the importance and value of healthcare professionals are widely recognized and appreciated — especially during the pandemic — the existence and effects of gender bias in the healthcare system must also be addressed, say advocates for women’s health.

Mason advised women to find physicians who are going to respect their opinions and take them seriously.

“Whether that’s a female or male physician, I think you’re going to want that same kind of respect and consideration,” she said. “When you have a feeling that something is wrong, you need to be persistent and you need to be an advocate for yourself.”