Cycling advocates say they are frustrated by the City of Ottawa’s Cycling Safety Review of High-Volume Intersections, a newly released report identifying dangerous intersections and recommending changes to prevent vehicle-cyclist collisions.

The review was undertaken in response to inquiries posed by Mayor Jim Watson and former Cumberland Ward councillor Stephen Blais in May 2019 after a 60 year old male cyclist was struck and killed in the bike lane on Laurier Avenue, in a hit-and-run in front of City Hall. The incident took place along a painted bike lane that ran alongside westbound vehicle lanes where cars are often shifting across the bike lane before turning on to Elgin Street.

The deadly collision led to calls for safety changes to that stretch of the roadway. Flexible posts now mark the cycling route more clearly and a stop sign at an on-ramp has been installed, CBC reports.

The Laurier bike lane, which is unprotected from vehicle traffic at intersections and other stretches of the avenue, has been the subject of considerable attention because it offers significant protection for cyclists where the lane is segregated but has also been the scene of serious collisions. In September 2016, a 23-year-old woman was killed while using the lane at the corner of Laurier and Lyon streets.

The report proposes safety improvements, short-term countermeasures, the estimated cost of long-term changes and more. Though the review initially identified 74 intersections based on a main criterion of three or more collisions over a five-year period, the recommendations ultimately focus on 34 of the most dangerous intersections.

The report is said to be pushing towards “an ultimate concept design that prioritizes cyclist safety, but also considers pedestrian, transit, and motor vehicle safety.”

However, the results are not being received with enthusiasm by all members of Ottawa’s cycling community. Advocates say the city needs to move urgently to fix safety problems that are already well known.

“It’s disappointing, but certainly not surprising,” said Trevor Haché, a member-at-large of the Healthy Transportation Coalition. “Despite the city’s claims that they’re showing commitment and progress towards safer transportation for all road users, we’re not seeing the investments that are needed to get us there in a timely manner.”

Jordan Moffatt, a board member of Bike Ottawa and author of the cycling blog Ottawa 3 Speed, said the report has “a lot of good things going for it,” but also emphasized that it is undermined by a lack of committed financial investment. “The city has to put their budget where their plans are if they do want to create a safe environment for active transportation,” he said.

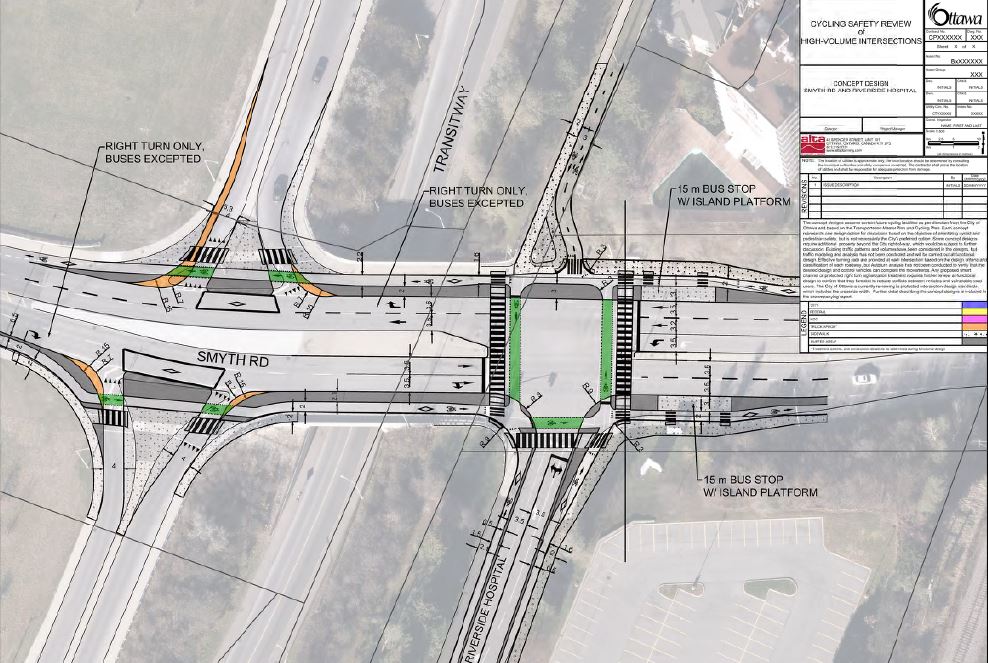

Although the report lays out the costs, there is no dedicated funding for the proposed improvements. According to the Ottawa Citizen, the changes would cost about $32 million. So far, $810,000 from the Road Safety Action Plan and Transportation Planning has been identified for one of the problem intersections — Smyth Road at the Riverside Hospital. But the proposed improvements to that site would cost $1.5 million.

Critics also note that intersections are not isolated — and to fully ensure that they’re safe, there needs to be a review of the surrounding cycling network.

Haché and Moffatt point out that although it has been almost 10 years since the city’s first segregated bike lane was constructed on Laurier Avenue, other cities — namely Montreal and Toronto — have far surpassed Ottawa in providing safe cycling infrastructure.

One example of a missed opportunity is the recent renewal of Elgin Street, which advocates say did not adequately priorize cycle-safe lanes and intersections.

Though Moffatt said the contents of the report signal a positive shift, he emphasized that what comes next will be more important.

“Just to make sure they actually follow through on that with all new projects — putting cycle tracks on both sides of the road, and safe intersections everywhere — would be the next step, and that of course means they’re going to have to spend some money on it,” he said. “Cycling infrastructure is not that expensive compared to other forms of infrastructure.”

Haché agreed, citing the cycling infrastructure in Paris as an example. “What cities around the world are showing us is that it actually doesn’t cost that much money. What is needed is the political will,” he said, referring to “massive improvements” cycling infrastructure in the French capital.

In his view, the lack of commitment in the report is emblematic of a “broken set of priorities” in Ottawa’s leadership and does not accurately reflect the danger posed by a lack of safe cycling infrastructure in the capital.

“We know, given the public health crisis and the climate change crisis, that we need to set a new direction, and that direction sees people driving cars a lot less frequently. It sees people walking and biking and riding public transit a lot more frequently, and unfortunately Ottawa is simply not making the investments that are needed to move us in that better direction,” he says.

“Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like the memory of the people whose lives have been lost is being well served by the inaction that continues at City Hall.”

The report was presented to the city’s transportation committee on Oct. 7 and will be considered as part of council’s budget talks this fall.