Research by scientists at McGill University and the University of British Columbia has found the Hudson Bay lowlands have the potential to be one of Canada’s most important landscapes in an era of climate change.

The study, led by UBC research associate Matthew Mitchell, sought to map Canada’s most significant “conservation hotspots,” or areas that offer the most environmental benefits to humans in one location.

“Before this study, there were no maps identifying the most crucial areas for conservation in Canada,” he said. “So we chose three of the most important services ecosystems can provide people that we also had data for — fresh water, carbon storage and recreation — and essentially marked down where these services overlapped the most.”

The study highlighted ecosystems in Canada as being particularly important in offering these environmental benefits. But the Hudson Bay lowlands were emphasized specifically for their massive carbon deposits.

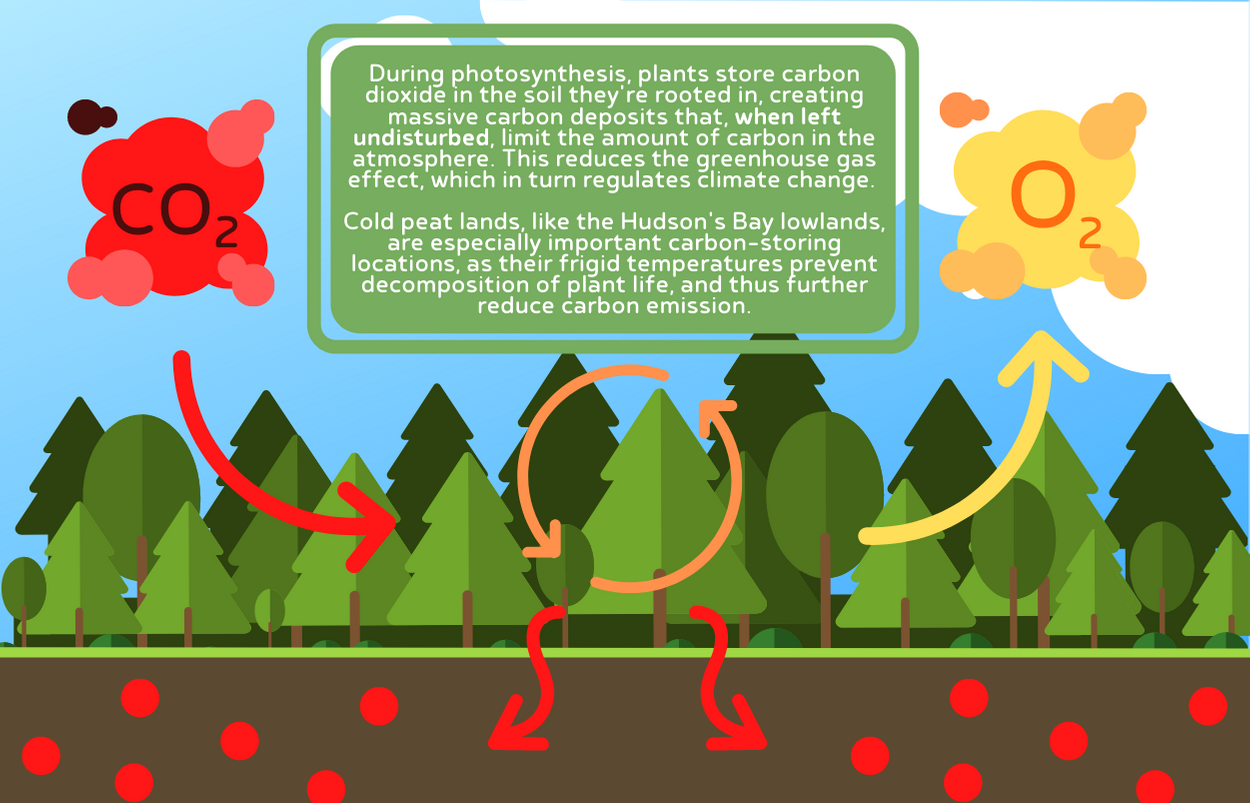

“Peat lands like the lowlands can store a huge amount of carbon,” he said, “which plays a huge role in regulating temperature and climate by controlling how much carbon dioxide is in the atmosphere.”

How carbon deposits help fight climate change

Information courtesy of Matthew Mitchell and the Government of Canada. (Graphic ©️ Pascale Malenfant]

Mitchell said that a large component of this study was ensuring the conservation hotspots were also determined based on how much they’re used by the human populations that live within them.

“Our work modelled and mapped human demand, too, and the Hudson Bay lowlands fell into that category of having a lot of resources, but also being useful to many people and communities — largely because of the climate change aspect of it, which affects everyone in Canada.”

Olaf Jensen, director of Environment Canada’s protected areas program, said the government has recently taken a particular interest in conservation hotspots in its commitment to protecting 30 per cent of Canada’s land by 2030.

“When you’re establishing a protected area, you’re inevitably making some tradeoff between conservation and development, which comes at a cost to Canadians,” he said.

“There’s a bunch of different frameworks out there for identifying different key biodiversity areas, but what’s essential is that we work to ensure that we’re conserving the places that give us the most bang for our buck. That way, we’re able to reduce the toll conservation takes on development.”

Mitchell’s study also found that only one per cent of Canada qualifies as conservation hotspots, many of which do not occur in areas already protected — an example of independently researched information that Jensen said helps reinforce the work Environment Canada is doing.

“We’ve been working to identify what we call ‘key biodiversity areas’ for a while now,” he said. “However, we still use studies like these to cross reference the work we’re already doing to make sure we’re not missing anything.”

Mitchell and Jensen emphasized that while large-scale research can lead to important developments in conservation — like national parks — the work of grassroots Indigenous communities to protect hotspots is equally important, especially in northern regions such as the Hudson Bay lowlands.

Ryan Barry is chair of the Hudson Bay Consortium secretariat, a coalition of research and conservation groups based in the Hudson Bay area that largely focuses on Indigenous self-determination.

He echoed Mitchell and Jensen’s sentiments, pointing out that larger studies may miss how these lands are conserved and how that affects Indigenous communities that live there. It’s important, he says, to consider reconciliation when defining what a hotspot is.

“These studies are obviously very important for determining how these lands benefit Canada, or even an entire province, but a lot of times, this research involves groups coming to these communities with their agenda, doing their research, and leaving without taking these communities’ needs into consideration.

Ryan Barry, chair of the Hudson Bay Consortium secretariat,

“These studies are obviously very important for determining how these lands benefit Canada, or even an entire province, as a whole,” he said. “But a lot of times, this research involves groups coming to these communities with their agenda, doing their research, and leaving without taking these communities’ needs into consideration.

“What we’ve been trying to do is enhance Indigenous self-determination by asking communities what their priorities are for environmental research and monitoring, because in terms of reconciliation, that’s just as important as how these lands benefit communities thousands of kilometres away.”

Mitchell said this is something he’s looking to incorporate into future studies, which he hopes will be able to address more environmental benefits that include the priorities of Indigenous communities.

“For this study, we chose three ecosystem services based on what would work best for a national park framework,” he said.

“But there’s so much more that can and needs to be accounted for,” he added. “Emphasizing the cultural importance of a specific place to its Indigenous populations is just one example, and involving these communities in conservation work is the only way we’re going to make significant progress.”