Indigenous, Black and People Of Colour (IBPOC) music workers say more representation and inclusivity in the live music industry can help professionals progress and make them feel like they belong.

A panel at the National Gallery of Canada on Thursday discussed recommendations to the Canadian live music industry, governments, funding bodies and workers for ways to support more IBPOC professionals within the industry.

The event began with key findings from a national report on employment gaps in representation and equity in Canada’s live music industry. Nicole Auger, manager of programming and community engagement at the International Indigenous Music Summit said, the study sought a framework for action.

“While the study provides a more accurate picture of the barriers, as well as the opportunities to addressing inequities in the industry, this is a starting point in the work that needs to be done,” Auger said.

The study and conversation come as Canada’s music industry struggles with a labour shortage, Auger said. More than 60 per cent of the live music industry is at risk of shutting down, the Canadian Live Music Association says.

“Three months into the pandemic, venues were closing permanently, skilled workers were leaving the industry for more stable work in other sectors and, as we know, many of them have not returned, so this conversation couldn’t be more important,” Auger said.

“Work cultures are signaling to them that their presence is of lesser importance.”

Nicole Auger, manager of programming and community engagement with the International Indigenous Music Summit and project manager of the Closing the Gap study.

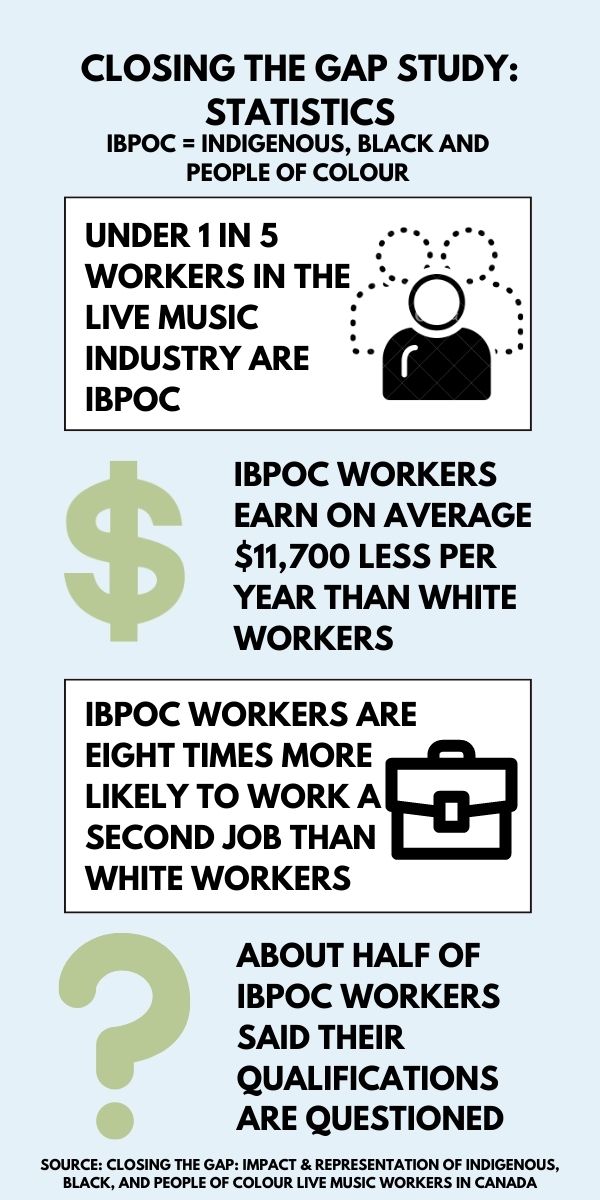

IBPOC workers make up 16 per cent of the live music industry despite representing 27 per cent of Canada’s population, according to the study, Closing The Gap: Impact & Representation of Indigenous, Black, and People of Colour Live Music Workers in Canada. The study referred to this aggregate of diverse, non-white people as IBPOC.

They were also less likely to work in gatekeeper positions, such as music venue owners, promoters, live event producers and festival programmers, according to the study that had 681 respondents from the Canadian industry.

Almost half of IBPOC workers said they felt they had their authority or qualifications questioned. None of the white respondents reported the same.

“It seems that IBPOC workers are not only working in spaces where they’re a demographic minority, but their work cultures are signaling to them that their presence is of lesser importance,” Auger said.

Even IBPOC workers with more authority face that adversity, said panelist Kwende Kefentse, the executive director of CKCU, a community-based radio station at Carleton University.

“Even when you get to the top of whatever organization you’re in, there’s still this other level where you often find there isn’t as much representation,” Kefentse said. “I think the sense is, ‘Oh yeah, I should be able to make a decision here,’ but then often, there’s the sense of mistrust.”

IBPOC musicians also have less slack from gatekeepers, said Naledi Sunstrum, creator of the Afro House music project, OK Naledi.

“If you are a person of colour and you’re standing on a stage, you cannot mess up – you have to do it perfect and when you get off stage, you have to be perfect,” Sunstrum said. “I work with other musicians who go to these bar scenes, get obliteratedly drunk… and continue to get hired. If I make that mistake, I am gone.”

The study partially recommends addressing concerns of IBPOC live music professionals who feel like they don’t belong, struggle to advance in the industry and lack mentorship.

This includes encouraging those in power to share their knowledge with more professional development opportunities, offering job shadowing, hiring more than one IBPOC person and ensuring entry-level IBPOC workers are supported at every stage of their development, Auger said.

The pandemic has also forced people to reflect and adjust as the industry moves ahead, said Yasmina Proveyer, a cultural funding officer at the City of Ottawa and co-founder of Axé Worldfest in Ottawa.

“Be ready to change your way you do things all the time,” Proveyer said. “Connect with someone who thinks totally different from you, but embrace that difference with grace.”

Click here to read all the recommendations and find more information about the Closing the Gap report.