Mental health advocates in Ottawa are sounding an alarm about rising demand for treatment and counselling services and bottlenecked access to such help when local residents — like others across Canada and around the world — are experiencing a pandemic-driven spike in isolation, anxiety and substance use.

A recent study by the Mental Health Commission of Canada estimated that one in five people live with mental illness at any given time in Canada. But Susan Farrell, vice-president of patient care services and community mental health at The Royal Ottawa Health Care Group, said she believes that number is “much higher” now.

“The pandemic is really difficult for everyone,” she said. “It’s created a lot of social isolation, isolation from services and other challenges. With that, we see both the worsening of people’s mental health, as well as the development of new mental health problems, including substance use.”

Just as physical and mental health are inextricably linked, the pandemic has had an immense impact — not only in this country, but globally.

This year’s World Mental Health Day on Oct. 10 highlighted inequities that exist in the health-care system about the availability of services for mental health. This year’s theme – “Mental Health for All” – underlined accessing treatment as a significant issue that has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis.

A Statistics Canada survey from 2018 showed that, out of the 5.3 million people who said they needed help for mental health issues, almost half said their needs were not met.

Increased wait times

Waitlists for counselling and therapy in Ontario can range from six months to one year, according to another study conducted by the Toronto-based Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. And experts agree these estimates are conservative in light of the added strain people are facing because of the pandemic.

Dr. Andrea Ashbaugh — a registered clinical psychologist, a psychology professor at the University of Ottawa and the director of its Centre for Psychological Services and Research — listed social isolation, burnout from overwork and financial stress (including loss of employment) as key factors contributing to increased rates of depression and anxiety.

“Many people are in need of that extra support right now," said Asbaugh. "That’s really what we’re seeing as a big driving force for the fact that the wait lists are so long to get mental health services right now. It’s in a state that we’ve never seen before really.”

The time between seeking treatment and receiving that treatment is critical, say experts. At that point a few weeks is a long time, let alone a few months. Even a few days can be the difference between life or death, they warn.

On the edge

“I’m standing at the edge of a cliff… and I need your help. I need help. And what you’re telling me is that you’re going to wait for me to jump off that cliff – hope I survive – and only then pick up the broken pieces.”

This is the analogy 26-year-old Ottawa resident Zoe Domitrovic used to illustrate the challenges she encountered while seeking help with mental health struggles.

She was given a referral to a psychiatrist and put on a year-long waiting list but was not offered any immediate assistance. Without any support or treatment, her mental health quickly spiraled downwards until she found herself at the bottom of the cliff.

“Then I started getting access to help,” Domitrovic said. “But it shouldn’t take for people to go there to have to get that help.”

Accessibility barriers

The barriers to accessing mental health care are nationwide and not limited to Ontario, according to Dr. Karen Cohen, a registered psychologist and CEO of the Canadian Psychological Association.

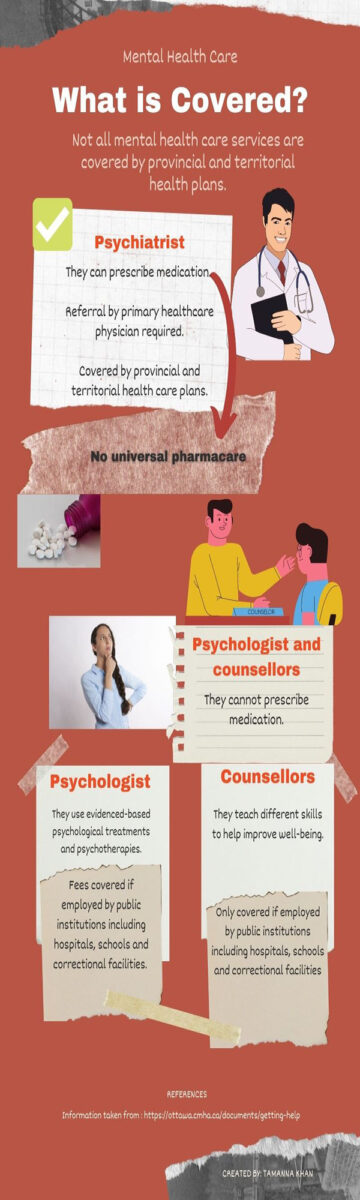

In Canada, the most common mental health problems are depression and anxiety, which can be effectively treated with evidence-based psychological treatments in the community by trained professionals.

The problem is that when these treatments are delivered by non-physicians, they are not covered by public medical insurance. This means that Canadians must rely on extended health-care insurance, which some people may have through employment or school. But otherwise, they have to pay out-of-pocket.

“I think there are huge inequities when it comes to health and health care. There’s no question about that,” said Cohen. “For example, if a community is disadvantaged in terms of stigma or discrimination or ... financially, it’s going to be much harder for them to access care.”

People who are uninsured or unable to afford these costs are not going to have the same treatment options available to them.

There are two main treatments for mental illness: medication and psychotherapy, or a combination of both. While medication might be sufficient in some cases, the psychological (or therapeutic) component is extremely effective in treating many mental health issues. Unfortunately, the problem with extended health-care insurance, according to Cohen, is that many have such low limits on coverage for psychological treatments and interventions.

“It’s like saying to someone, ‘Here’s 10 cents, go get a loaf of bread,’” she said. “If you put a cap of $300 or $500, but the average person needs 15 to 20 sessions, which costs more like $3,000 or $4,000, you create access gaps … When we talk about not wanting to have a two-tiered health-care system in Canada, we have one already.”

While treatments for many physical health conditions are covered, she and other advocates say, services for mental health remain an underserved area in Canada's health-care system. The MHCC estimates that 12 million Canadians do not have access to employment-based psychotherapy benefits.

“And that says something about not only how we value mental health, but how we value people working in that area, too," said Cohen.

Filling in the gaps

Now that we are aware of the access gaps that exist in services for mental health, we need to ask what it’s going to take to change, said Cohen. In her opinion, public policy needs to be reformed.

In a recent column for The Hill Times — published before to the Oct. 26 naming of veteran Liberal MP Dr. Carolyn Bennett as Canada's first Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health — Cohen listed eight recommendations to mend the access gaps in the public and private health.

She said it will take a lot of commitment from individuals, health providers and policymakers to address the issues. While people are being more vocal about mental health in Canada, Cohen concluded that not only do they have to agree on strategies, but also implement them.

“I think how it’s going to change is different people need to agree — not just to talk about doing something differently, but doing it …. Where we have work to do is once people are talking about it, to make sure the services are there when they need it.”

Expanding services

As a result of the pandemic, how services are being accessed has changed and continues to evolve. The ability to meet virtually is extending access to those who would otherwise be isolated.

Although this is one way that accessibility is being improved, there are still disparities in terms of technological advancements. Not everyone has high-speed Internet. Others may live in crowded households in which there is limited privacy.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, an MHCC pilot-project document, states that equitable access to psychotherapy is an important policy issue. It outlines how the gaps in services and supports for mental wellbeing across Canada have contributed to high rates of unmet need, greater financial barriers for Canadians without insurance benefits for psychotherapy and the underfunding of mental health services in Canada.

Ontario Health announced that in April 2021 the IAPT pilot project would be expanded into the Ontario Structured Psychotherapy Program, which offers free one-on-one counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, online courses and group sessions to participants. Clients can self-refer by completing on online form.

“I’m standing at the edge of a cliff … and I need your help. I need help. And what you’re telling me is that you’re going to wait for me to jump off that cliff – hope I survive – and only then pick up the broken pieces.”

Zoe domitrovic describes how her call for help was ignored

The U of O's Centre for Psychological Services and Research provides psychotherapy and assessment services to children, families, couples and adults. CPSR is not only a community mental health centre, but also a training facility for students. At any one time, there are 50-60 clinical psychology graduate students providing mental health services under the supervision of licensed clinical psychologists.

What makes CPSR more unique and accessible is that it provides reduced fees to clients, including a sliding-scale system based on financial need. The maximum cost for an individual therapy session is $50, but the fee can drop to $5.

Ashbaugh, director of the CPSR, emphasized that, although the services are far more accessible than most offered in private practices, the centre does not compromise the quality of care that clients get.

“The part that is challenging, and this is not unique to our services, is simply having the space and the resources to provide services,” she said. “So certainly making it more accessible within the public system would be helpful, but that also means making sure that the people providing services are paid appropriately by the public system.”

The inequities within the system need to be addressed, added Asbaugh. In addition to increasing the number of psychologists, they need to be paid more to work in public institutions, otherwise they will continue to go into the private sector.

Reaching out for help

Whether speaking from personal experience or professional opinion, when asked what advice they would give to someone struggling with mental health issues, advocates' answers were the same.

The first step is to reach out and talk to someone about what you are going through.

“And that's what I would say,” said Domitrovic. “Reach out to people that you can trust to have that conversation. I have my circle, people I can trust and people to help guide me. That made it a lot easier.”

Seeking mental heath help from someone who recognizes the difference between “there is” a stigma and “there are” people taught and teaching there is is no easy task.

Harold A Maio