COVID-19 information coming from social media, friends, family, co-workers and community leaders may be contributing to vaccine hesitancy among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, a survey presented last week at the Metropolis North America Migration Policy Forum indicates.

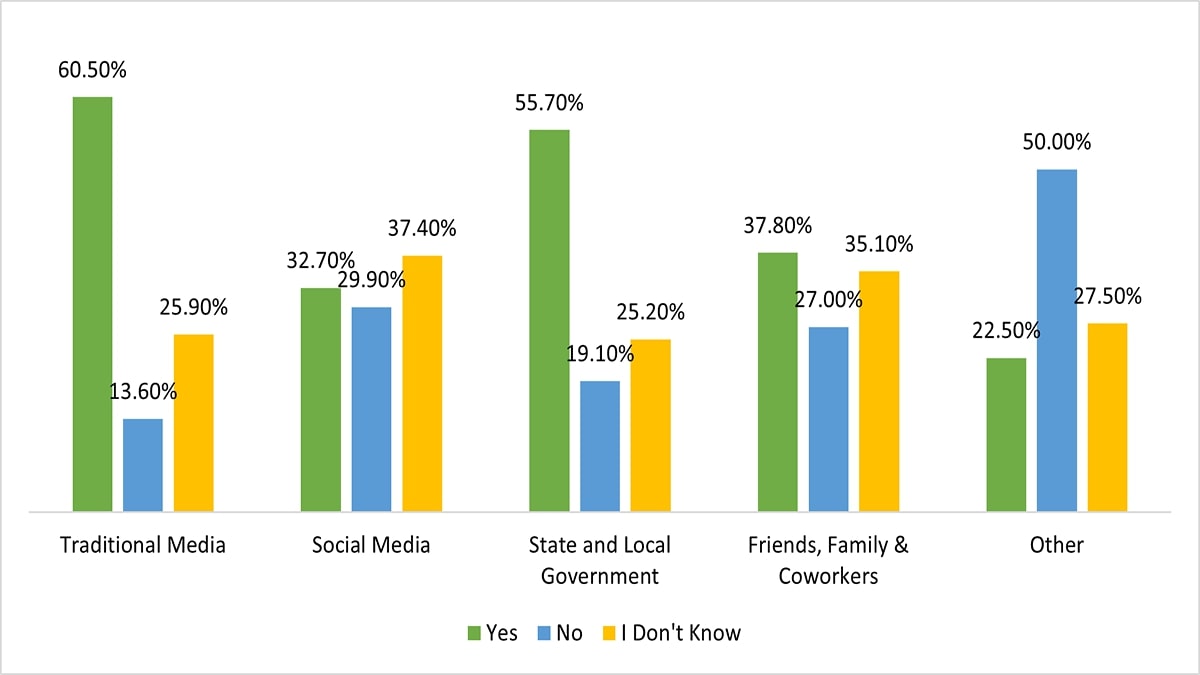

In contrast, Indigenous peoples who use traditional media, local and provincial governments for information on the virus expressed more willingness to get vaccinated, the survey presented by Avery Hallberg, a graduate student at the University of Manitoba, showed.

Hallberg, along with a team of researchers at the university, has been conducting rolling panel surveys on vaccine intentions since September 2020 in collaboration with Association for Canadian Studies and Leger Marketing.

Hallberg said family, friends and coworkers seem to have “a strong influence” on respondents as does social media, when it comes to accepting to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

According to data collected in December 2020, 13.6 per cent of traditional media users and 29.9 per cent of social media users among Indigenous respondents did not intend to get vaccinated.

In addition, 27 per cent of Indigenous individuals who relied on friends, family and co-workers for COVID-19 information and 50 per cent of those who gathered their information from other sources such as community elders and religious leaders did not want the jabs, Hallberg said.

One of the most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy is skepticism about the vaccine’s safety.

Lori Wilkinson, professor of sociology and criminology at the University of Manitoba, said 13 per cent of Indigenous Peoples and 12 per cent of non-indigenous say they do not know if vaccines are dangerous in general.

“That category of don’t knows, are the interesting group because we think that they could be informed to make a better decision for themselves,” said Wilkinson, one of the lead researchers of the ongoing study.

Wilkinson said she feels that some hesitancy happened because the federal, provincial and local government messages to encourage vaccination have not captured the group who were unsure about vaccines.

She referred to promotional messages, some of which asked people to get vaccinated “if they want to go to a hockey game” or “hug their grandma.”

She said these messages aren’t capturing the reasons why people are hesitant.

According to the survey some of the main reasons why Indigenous people did not want to get vaccinated were — the vaccines are too new or rushed, the fear of side effects and allergic reactions.

“What was a bit surprising about this is that even amongst Indigenous people, the trust in government didn’t come out as often as we thought,” Wilkinson said, referring to the reasons for hesitancy.

Biomedical experiments have been carried out on Indigenous communities and residential schools in Canada, often without individual consent.

Wilkinson said, however, most of the hesitancy was about the novelty of the vaccine, as opposed to “I don’t trust the government, because they’re making me take it.”

The survey on vaccine intentions and hesitancy is part of a bigger study on the social impacts of COVID-19, being conducted in Canada, the United States and Mexico with funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Each week, about 1,500 people from each of the three countries are polled on the internet. A qualitative survey is also completed every two months among a larger group in all three countries.