By Jackie Bastianon, Michael Charlebois and Caroline Mercer

“Your life can change in an instant. Don’t drive high,” a banner on the Government of Canada’s website reads. With legalization fast approaching, the federal government is delivering a clear message about cannabis-impaired driving.

In a 30-second advertisement, shot to look like a social media livestream, a group of young people smoke cannabis before getting into a car to drive to a party. Moments later, the car’s window smashes as an accident occurs.

The federal campaign was launched in association with Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and bears a similarly grim message to other MADD commercials discouraging drunk driving.

But the risks associated with driving high — and the best way to police it — remain contested.

Local police have opted out of using federally approved saliva samples, and will rely on blood testing to determine impairment. But it’s still unclear how much THC in a driver’s blood makes a person legally impaired and there are discrepancies in data available on cannabis and driving.

“The government has said they’ll crack down on drug-impaired driving, and the public health messaging is quite clear: people should not be driving after they’ve consumed cannabis,” University of British Columbia research scientist M.J. Milloy said.

The current method used to determine impairment by Ottawa Police is as follows: An officer suspects that a driver is impaired and performs a standard field sobriety test (equivalent to that of alcohol), an arrest is made if the test is failed, and the driver is evaluated by a drug recognition expert in custody to determine whether charges will be laid pending a blood sample.

It’s a strenuous process. MADD victim services worker Grant Thomson described it as a “resource eater,” and many police forces have already spoken out about the logistics of testing for drug-impaired driving.

The complex process may have led to the low number of local collisions linked to drug-impairment in the years leading up to legalization.

According to an analysis of City of Ottawa collision data by Capital Current, drug-impaired driving contributed to just 72 of 107,558 crashes in Ottawa between 2014-2017, a small fraction — 0.07 per cent — of all collisions over that time. Alcohol-impaired collisions make up roughly one per cent of crashes.

Drug-impaired driving accounted for only 0.07 per cent of all 107,558 collisions in Ottawa between 2014-2017. Fatigue and alcohol were responsible for 0.4 per cent and nearly one per cent of collisions, respectively. Inattentive driving was the greatest threat, accounting for nearly one-quarter of all collisions.

Collisions data low, but many drivers still high, according to StatsCan

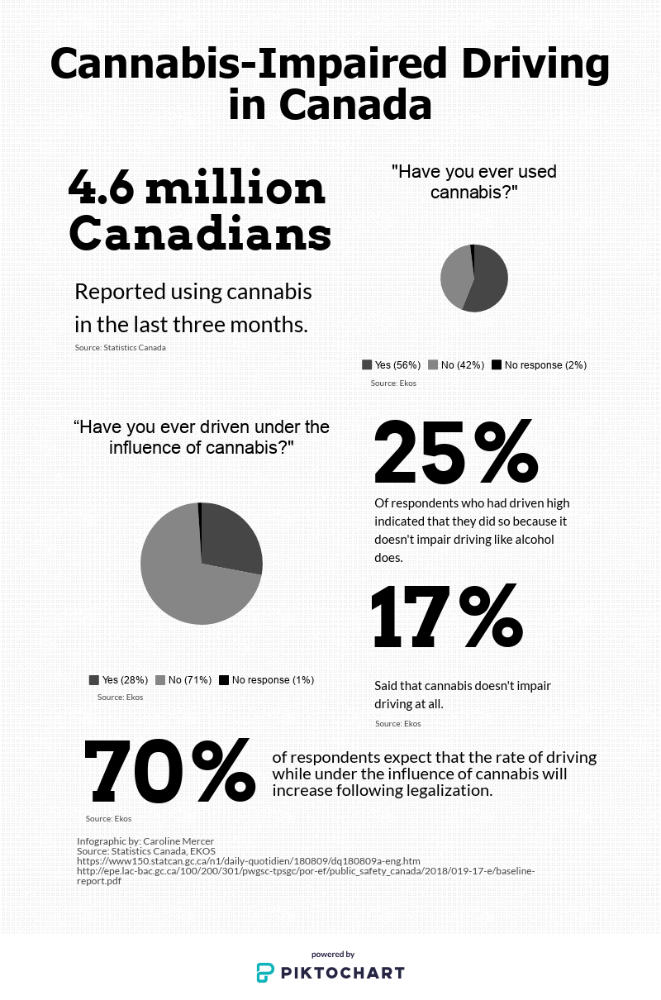

According to a 2018 Statistics Canada survey, one in seven cannabis users with a valid driver’s licence said they had driven a vehicle within two hours of consuming cannabis.

Seventeen per cent of Canadians who had driven while under the influence of cannabis said they did so because they believe cannabis doesn’t impair their driving, according to a separate study by Ekos Research.

In 2015, a Statistics Canada study revealed that the number of alcohol-impaired driving incidents resulting in bodily harm was 30 times higher than drug-impaired cases.

Alcohol-impaired driving is consistently responsible for a higher number of incidents causing death and injury than drug-impaired driving is. However, as alcohol-impaired driving incidents decrease, drug-impaired incidents are slowly climbing, perhaps due to increased detection or a growing rate of drug-impaired driving.

Senate research looking at U.S. states

Research being done for Canadian parliamentarians is focusing on information from American states where cannabis has already been legalized.

M.J. Milloy co-authored a 2018 study about the public health effects of cannabis legalization. The study was done for the Canadian Senate and analyzed data from Colorado and Washington state.

“When we did our study on road safety, we didn’t find significant differences [in fatal accidents] between states that legalized, and states that didn’t,” Milloy said.

Although the data found an increase in THC-positive blood samples in fatal collisions, the study could not determine what role THC played in these collisions.

“A significant limitation of these studies is the inability to assess the level of driver impairment,” the report reads.

In fact, Milloy’s report suggests cannabis may have had a substitution effect in which young people are limiting alcohol use and opting for what they believe is a “safer” impairment with cannabis.

But such research is contested by safety advocacy groups.

“It certainly doesn’t reflect the research that has come through MADD,” Thomson said.

Thomson refers to two MADD studies which looked at crash data from 2014.

In that year, cannabis was reportedly involved in 19 per cent of fatal collisions, although the data do not show if the driver was the impaired person. Another study shows cannabis was the most common substance found in fatally injured, drug-positive drivers, making up 45 per cent of the total.

Issues with classifying impairment

Whether cannabis-use is a factor in collisions or not, measuring impairment levels is a grey area in cannabis research.

“Nobody can dispute alcohol numbers,” Thomson said. “Here are the effects, here are the people that were killed, here’s how much alcohol was in their system. They’re very explicit.”

Thomson said that the duration of impairment, tolerance levels, THC levels, and mode of consumption are all factors which can affect cannabis users.

Then, there’s the legal limit of THC. Under the federal government’s Cannabis Act — which will come into effect on the day of legalization — any driver with five nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood could receive a criminal conviction punishable with a fine up to $1,000. Subsequent offenders can face up to 120 days in jail.

Denver-based defence lawyer Jay Tiftickjian says the five nanogram measure, which is also used in jury trials in Colorado, presents a “real danger” in the courts due to a lack of scientific validity.

“Frequent users have a baseline of THC that could exceed this amount,” he said. “There’s the distinct possibility that people who aren’t impaired could be charged and convicted.”

With legalization around the corner, Milloy pointed out that there is still “no good test of cannabis impairment yet — certainly not on the level of blood-alcohol content.”

Plans for policing

Thomson fears governments and police aren’t ready.

“In the coming months, there’s absolutely nothing that can be done,” Thomson said.

“Our thought process right now is that we’re definitely we’re going to see a distinct increase in [drug-impaired collisions].”

Local law enforcement feels the same way.

“As seen in other jurisdictions that have legalized cannabis, they have seen an increase in impaired driving by drugs, as well as an increase in accidents due to drug impairment,” Ottawa Police Const. Amy Gagnon said in an e-mail.

As it stands, Ottawa police will continue to rely on existing methods. “Our approach will not change,” said Gagnon. “It has been proven to be reliable.”

Cannabis will be available for legal purchase online in Ontario on Oct. 17, with pot shops set to open in April, 2019.