The maple leaf is a scary sight for opposing hockey teams at the international level, often foreshadowing a loss at the hands of superstars such as Connor McDavid.

But despite professional success, youth participation in Canadian hockey has been steadily declining. For example, Hockey Canada saw a six per cent drop in the number of players in 2019-2020 from the previous year, as reported by The Athletic.

One reason for the falling numbers could be accessibility to the game for low-income communities.

“Many young people experience barriers to participation by virtue of the family situation,” said Sharon Jollimore, director of Programs and Innovation at the Ottawa Community Housing Foundation (OCHF).

“A lot of the families involved with OCHF are newcomers to Canada and participation in youth sports often gets pushed down the agenda,” she said.

Jollimore says there are more than 9,000 youths in low-income Ottawa communities. These young people could be the key to bolstering Canada’s waning participation in hockey if they can get a chance to play.

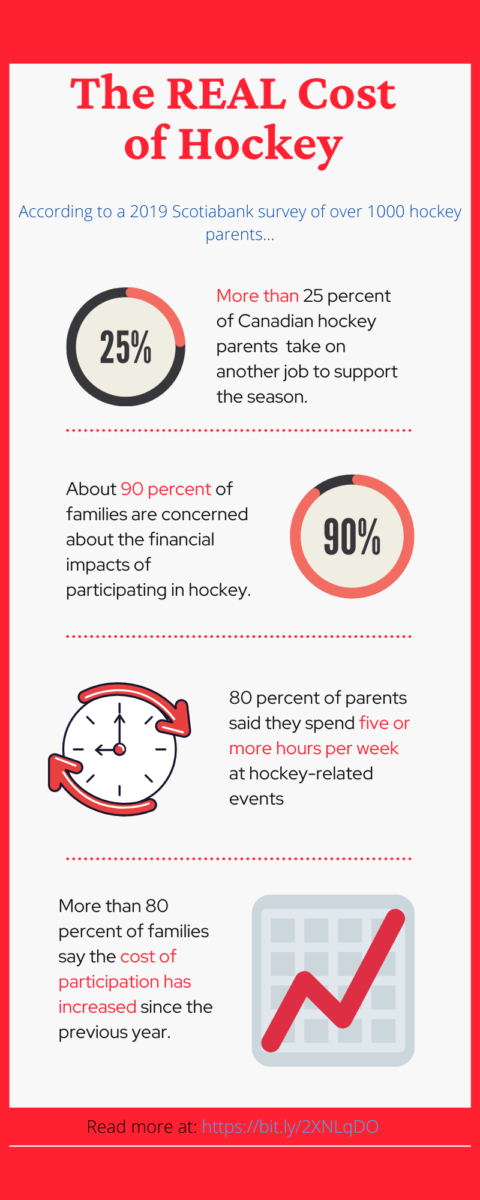

“I think the biggest constraint to participation is the cost. … It’s not just registration and equipment,” she said.

For instance, tournaments are a big part of hockey culture. Programs like Canadian Tire’s JumpStart might help outfit a child with equipment, but they don’t cover gas, flights, or a weekend at the local Inn. In the Greater Toronto Hockey League (GTHL), the largest minor hockey league in the world, the cost of an away tournament in 2014 was $1,000.

“All of these things add up when you’re a family in a low-income situation. … There’s a lot of things that stack against [participation],” says Jollimore.

Alexandra Zannis, social policy and communications co-ordinator with the Canadian Association of Social Workers, said “often the onus ends up falling predominantly on youth who shouldn’t have to ask if they can afford to pay for equipment and fees … or food.”

Zannis said that there are government programs that can help families access youth sports, but you have to know where to look.

“Accessing government support can be tricky and filled with hoops individuals have to jump through to access them or qualify,” she said. Outreach programs and frontline services alleviate some of the problems, but Zannis noted that often it’s a “band-aid solution on societal or structural problems.”

Sean Tobin, Assistant Referee in-Chief of Hockey Eastern Ontario (HEO), says access and cost of play isn’t the only thing preventing some kids from lacing up a pair of skates.

According to Tobin, the HEO deals with complaints about discriminatory comments from players every year. These instances only serve to further isolate hockey from racialized and low-income communities.

“We have to send a message to communities, such as the BIPOC community, that we want them involved,” Tobin said. He hopes that referees can lead by example by cracking down on discriminatory comments.

“When the player hears that, that’s problematic enough. When the player sees that [referees] do nothing about it, as a leader, that’s a major problem. It’s an integrity issue,” says Tobin.

A 2016 census found that 20.8 per cent of people of colour in Canada are low-income, compared to 12.2 percent for non-racialized individuals. When discriminatory comments are made at the rink, yet another barrier presents itself to low-income communities.

Nonetheless, outreach programs do exist. The Ottawa East Minor Hockey Association (OEMHA), for instance, features a program that helps families attain financial assistance for children four and up.

However, the existence of a program doesn’t necessarily make it accessible. As Alexandra Zannis notes, bureaucratic processes and “hoops” can get in the way.

Going forward, generating youth participation in low-income communities may be critical in stopping the decline of hockey participation. Cracking down on discrimination and increasing accessibility for low-income communities could be the place to start.

So sad as I read this from South Texas. We have poor latino and black communities that will never have a chance to experience the game of hockey. I have asked community leaders for funding to introduce the game to underprivileged youth and unfortunately with only one sheet of ice in this large city (San Antonio), I don’t see it ever happening.