Scientists from around the world are on the cusp of choosing a natural landmark to represent the point in Earth’s history when human activity began to significantly impact the planet.

A small lake in Milton, Ont., is one of 12 locations from around the world nominated to symbolize the start of the Anthropocene Epoch, a proposed new time period in the planet’s geological history typified by humanity’s unmistakable impact on the land, water and air.

Traces of pollution beginning with the Industrial Revolution, for example, as well as the enduring signature of 20th century nuclear bomb tests, are among the markers scientists can detect in the lake-bottom sediments at Crawford Lake and at other sites vying to become the so-called “Golden Spike” representing the onset of the Anthropocene.

Crawford Lake’s competitors range from Flinders Reef in Australia to the Antarctic Peninsula. The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), made up of members of the International Union of Geological Sciences, announced the candidates at a conference in Berlin earlier this year.

The site chosen by the AWG will be recognized as the newest Golden Spike, a geological reference point used to identify a significant change to the Earth and offering a window into the past.

Paul Hamilton, a scientist at the Canadian Museum of Nature and a researcher working on Crawford Lake’s pitch, stresses the global importance of determining the Golden Spike.

“It will be giving the starting point — a date, a time and a place — where we as the human species began to see our contribution to the disturbance of the Earth,” said Hamilton.

Francine McCarthy, a professor of earth sciences at Brock University – the main institution spearheading the case for Crawford Lake – is a voting member of the Anthropocene Working Group. She says the lake shows records of both global and local magnitude — proof of nearby Indigenous settlements that lived on the shores of the lake thousands of years ago, alongside evidence of wide-scale modern events such as the Industrial Revolution.

“The global impact was felt in this little rural, isolated lake,” she said.

Once a site is determined to be the “poster child” for the epoch, McCarthy says, the Anthropocene will be on track to becoming a part of the official geological time scale.

Tim Patterson, a researcher and scientist at Carleton University — another one of the main institutions contributing to the research on Crawford Lake — calls the geological significance of the lake “mind-boggling.”

“There’s nothing like it in Canada and perhaps not the world,” said Patterson. “It’s a one-in-a-million lake.”

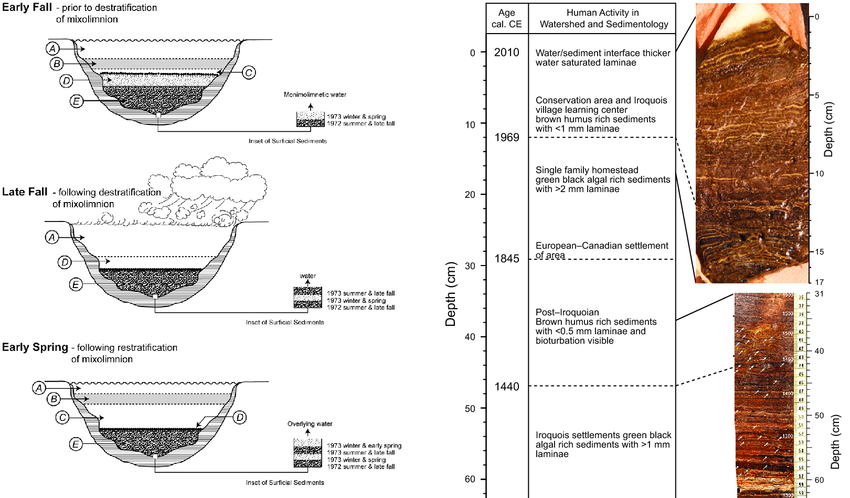

What makes Crawford Lake so significant, Patterson says, is the way its layers interact with one another. It’s a deep, meromictic lake, meaning the layers of water don’t intermix: the top layer mixes with help from the environment – such as animal contact, rain or wind – while the bottom layer is more dense and does not combine with the top. The separation allows sediments to sink to the lake’s bottom, where they gather in distinct layers and become preserved, forming a geological snapshot of history.

McCarthy describes the sediments as being “seasonally laminated,” comparing the occurrence to the “rings inside a tree.” She and her team have spent the past four years understanding why this happens.

At Patterson’s lab, he and his research team collect evidence of the layered sediments at the bottom of Crawford Lake using a freeze core, a method commonly used to investigate lake bed sediments.

“The freeze cores are basically long chambers. You fill them up with dry ice, alcohol and slurry. Then you pound it all together, you seal it up, and you lower it to the bottom of the lake,” Patterson said.

“Because dry ice is very cold, the lake sediment freezes to the surface of it. You pull it out after about half an hour or so and then you have a beautifully preserved, perfect record of the lake bottom sediment.”

‘Since the 1950s, the planet has been different than it had been for probably millions of years before then. So the changes since the mid-20th century are of a greater magnitude than the end of the ice age, or any big things that happened in the last few million years.’

— Francine McCarthy, earth sciences professor at Brock University and Anthropocene Working Group voting member

“We are companions in that way, scientists and Indigenous people,” said Catherine Támmaro, an artist, Indigenous Elder and seated Faith Keeper of the Wyandot of Anderdon Nation. Támmaro’s ancestors are believed to have lived on Crawford Lake many hundreds of years ago.

Crawford Lake’s research team has also been working alongside local Indigenous people to preserve the land’s rich history in their science.

Támmaro says one of the appeals of working with the research team was their “scientific language and worldview,” adding that “how it sits next to Indigenous understandings is a beautiful thing.”

“What prompted me to start making art was an absolutely unquenchable urge to connect with questions that I had about my own existence,” said Támmaro. “Crawford Lake is a huge connecting point to my people’s past, to my history and to cultivating an awareness of who I am through the land, through the water in that space.”

Támmaro’s art piece was inspired by Crawford Lake and the oral legend the BeadSpitter. She says the piece is symbolic of the wampum belt, a belt created to mark agreements, record treaties and disputes between Indigenous communities. Támmaro says this art piece records a conversation between her and the lake.

The piece, she says, is not a wampum belt, which is an “important distinction.” Rather, the lake is representative of a wampum belt, “(a) representation of the striations that were caused as the BeadSpitters want them … layer upon layer, upon layer, upon layer.”

While the sediments – shown in her art using beads – represent time, they are also a recording of the “spiritual presence of the lake.”

On top of that, the lake’s record shows evidence of Indigenous peoples’ presence through agriculture.

“There’s corn pollen in the sediments that reflect our presence there,” Támmaro said. “It anchors us in that spot in a way that perhaps nothing else could, other than memory or other people’s records.”

Crawford Lake’s ability to preserve sediments makes it an excellent way to recognize human activity over time, Hamilton explains, stating that “there’s a very good record” of especially the past 600 to 700 years.

During these years, the record shows three distinct periods of human impact: the Wyandot of Anderdon Nation settlement in the 1400s, shown through agricultural remnants; the colonization of North America in the 1800s, which saw deforestation and land alterations and the industrialization of the modern world, beginning in the 1950s and continuing today.

“Since the 1950s, the planet has been different than it had been for probably millions of years before then. So the changes since the mid-20th century are of a greater magnitude than the end of the Ice Age, or any big things that happened in the last few million years,” said McCarthy.

In comparison to other sites, Hamilton continues, Crawford Lake is the only one that is close enough to where these major changes were happening. Contrastingly, scientists at other locations, such as the ones in China and Antarctica, argue their sites’ importance by noting their distance from the changes. “(They) would be saying, you know, we’re far away from the industrialization and we could still see (its impacts),” said Hamilton.

The search for the Golden Spike is a hard one, though it is not the end of the AWG’s journey.

Hamilton explains that the first step as a scientist is getting your site chosen as the representative site for new human-shaped geological epoch.

Traditionally, locations chosen as a Golden Spike will have a physical metal spike placed in them to formally recognize the start of an era in geological history. For example, the marker for the Ediacaran Period in Earth history — which began about 635 million years ago and lasted nearly 100 million years — can be found on a cliff of exposed rock in South Australia. The unique features of the site, including certain rock formations and embedded fossils, are representative of the geological processes and long-extinct animals of that time in the planet’s history.

If Crawford Lake is selected as the Golden Spike for the Anthropocene era, a spike would be placed on a publicly displayed core that has been removed from the lake bottom.

The second step, Hamilton says, is to present as much information as possible to ensure that everybody, including scientists working on different sites, are on board to designate a new epoch called the Anthropocene.

If Crawford Lake is not chosen, its team will continue to collaborate with other scientists involved in trying to define the epoch using the winning site.

Hamilton says even if the team working on Crawford Lake’s proposal loses, “they will still try to help and research and fight to establish the start of the Anthropocene,” he said. “This is just the start.”

“I expect all of the other sites will be doing the same thing,” Hamilton said, noting that this is the ultimate goal. Scientists are rooting for a site to be chosen, he says, whether it’s theirs or not, “because the human disturbance now is so great that we just can’t avoid talking about it anymore.”

Voting will begin Sunday, Dec. 18, but it is a long process and deciding the winner could last until next year.

Impressive article. As a former geology teacher long ago, I am thrilled to read about an Anthropocene Epoch in our geologic history. Good luck to Crawford Lake…