As the City of Ottawa embarks on a new official plan – the blueprint to guide future development in the nation’s capital – local groups are resisting a possible push to expand the urban boundary.

Urban boundaries safeguard green spaces and dictate where and how intensively developers can build. While Ottawa’s projected growth suggests expansion of developable areas might be necessary, opposition groups say the opposite is true.

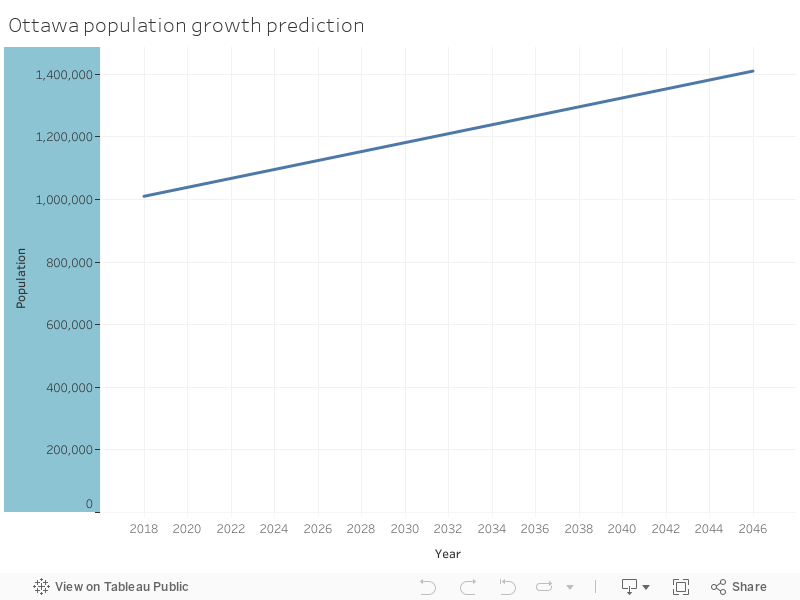

The new official plan is expected to be presented to council by 2021 and will play a huge role in determining how Ottawa will evolve by 2046. By then, it is projected that Ottawa’s population will increase 40 per cent from 2018 to 1.4 million. As a result, the city predicts that the number of private households is expected to jump by almost 195,000 in that time.

Members of city council have not decided to include urban expansion within the new plan. The vote was originally to be held March 30, but will now take place this May.

The City of Ottawa’s existing official plan proposes a vision for the city’s growth and includes a policy framework to guide the city’s physical development by 2031. This extensive document includes guidance on items such as development of land, infrastructure changes (roads and parks), zoning, preservation of natural systems and expansion of the “urban boundary.”

This multi-year process determines the likelihood of additional urban development “sprawl” — adding new land to the urban boundary in a number of locations, excluding agriculture spaces to be preserved as farmland.

The new plan could propose changes, including expanding Ottawa’s boundaries past the current urban limits to allow for cheaper home construction — a move activists say would increase car dependency and social isolation. Already-established urban boundaries, such as those around Kanata, could be expanded to allow more single-dwelling units to be built. This would allow relatively fewer people per property compared with high-density developments in the central part of the city.

However, no changes are certain until the councillors meet and decide in May.

The main debate is centred on whether the city should allow urban expansion rather than focus on increasing density through “residential intensification” — the construction of multi-storey buildings such as apartments and condos, which can pack more people into relatively small parcels of land. This is seen as a more feasible, environmentally friendly approach that has been endorsed by organizations such as Ecology Ottawa.

Ottawa’s current plan

The current official plan was adopted in 2003, although amendments have been made since.

In 2001, the former cities of Ottawa, Nepean, Gloucester, Kanata and seven other urban and rural municipalities such as Vanier and West Carleton were amalgamated into a single, new City of Ottawa.

Council last debated expansion of the boundary in 2009. It was ultimately expanded by 1,104 hectares in 2012 following a controversial decision by the Ontario Municipal Board, a provincial arbitration body that settles land-use disputes.

In a survey conducted by Greenspace Alliance of Canada’s Capital, an umbrella organization of citizen groups working to protect Ottawa’s green spaces, 10 out of 11 city councillors who responded to questions indicated they’re against urban expansion. Another 12 councillors did not respond to the survey.

Intensification as an alternative solution

“Intensification is the very first step we need to take to ensure Ottawa develops in a green way,” said Liza Odokiienko, who is spearheading Ecology Ottawa’s Hold the Line campaign. The campaign aims to increase intensification, which includes reducing the supply of single-family homes with higher-density dwellings and increasing infrastructure in already developed areas.

Odokiienko explained that intensification has been adopted by many cities as the best approach to accommodate a population boom while addressing affordable housing needs. Increasing density in existing residential areas – essentially replacing many single-family homes with multi-unit dwellings — reduces the need to develop new land for housing and increases the person-to-building ratio of current communities.

“If the boundary expands, it’s not necessarily going to (include) complete communities … this can cause social isolation and a dependency on cars,” said Odokiienko.

Ecology Ottawa wants to increase intensification to 70 per cent, a 16-percentage-point increase from the previous target, and create “15-minute communities.”

“If all our communities are built within walking distance or a 15-minute commute time, that means people don’t have to buy cars — you can just walk or rely on public transportation which in turn reduces emissions, and even traffic,” said Odokiienko.

Although the 70-per-cent target is much higher, it is not unrealistic, she insists.

“(Ottawa) exceeded our expectations for intensification, and they weren’t very high. But because they did exceed them, it makes me think that we can do it, we can make this city liveable and walkable, and people will not have to rely on cars,” said Odokiienko.

Trevor Haché, co-founder of the Healthy Transportation Coalition, said expanding the urban boundary would add more strain on Ottawa’s public transit system.

“I think for Ottawa to function well, we need to have an excellent, reliable, frequent public transit system,” said Haché. “Providing that … is very difficult in a sprawling city, because it costs a lot of money to provide services to low density areas of Ottawa.”

Paul Johanis, chair of the Greenspace Alliance, said his group — along with about 20 other organizations and individuals across Ottawa — has held its own consultations about the direction of the city’s new plan.

“We are collectively against any expansion. We’re thinking in the climate emergency, that’s like a no-brainer that you shouldn’t be expanding, you should be building in, you should be building up,” said Johanis. He emphasized that the recently announced housing emergency by city council should play a role in the decision-making process.

“You don’t solve that (emergency) by building suburbs 30 kilometres away from the city centre,” he said.

Johanis said the alliance’s calculations show that if the city’s target of creating 54 per cent of housing through intensification was increased to 68 per cent, the urban boundary expansion would not be necessary.

Potential expansion

The Greater Ottawa Homebuilders’ Association, however, believes urban expansion and intensification can go hand-in-hand.

“Realistically, we will need some houses built further out because we simply can’t build units fast and cheap enough for everyone to live downtown,” said Jason Burggraaf, executive director of the GOHBA.

“By building further out we can give people the diversity of housing and price range that they need while promoting intensification to reduce the environmental effects.”

“Without urban expansion, people will end up building outside the boundaries (of the City of Ottawa) to suit their housing needs and commuting to Ottawa, so they are using our infrastructure without paying our taxes,” said Burggraaf.

New urban centres, like the one proposed in Barrhaven, might help reduce the environmental effects of urban expansion by increasing the density of development in existing suburban areas. Similarly, the LRT system – in its fully realized state – will help eliminate the need for at least some car commuting from outlying areas.

“If you look at the numbers, some of the fastest-growing areas are not in the downtown core, and focusing intensification in these areas — while allowing some degree of urban expansion — can reduce the need for people to commute all the way downtown and back,” said Burggraaf.

By doing so, he said, commutes will be shorter and residents will not have to rely on cars.

An executive with Richcraft Homes, a prominent Ottawa developer, fully supports urban boundary expansion.

“Richcraft believes that City staff will recommend expanding the boundary to conform with provincial policy,” said Kevin Yemm, Richcraft’s vice-president of land development, in an email. Yemm refused to comment further, and did not explain how this would conform to provincial policy.

However, the review of the official plan is being undertaken by the city under the provisions of provincial policies.

For Tyler Boswell, a Carleton University student, a potential urban expansion means a loss in greenery that people in the city may need.

“It takes longer to get to those outdoor spaces,” said Boswell. “I’ve always found destressing in the environment super relaxing and, you know, that does the trick for me. If you keep getting further and further away, it just gets harder to get to (rural areas).”

So in 2046, there will be 195,000 private households in Ottawa?

Thanks should have read by 195,000 not to 195,000

Hope far more so costs will go down as well as Ottawa needs new houses and not just condos or apartments.