The executive boardroom at Ottawa Police Service’s Elgin Street headquarters has been renamed in honour of late Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook, who has also become the namesake of a city park in Ottawa’s Sandy Hill neighbourhood.

The renaming of the “Tunnganarniq boardroom in honour of Annie Pootoogook” was made official in late September by Ottawa police’s community equity council, just ahead of the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in Canada.

Heidi Langille, co-chair of the council’s Indigenous relations committee, explained in a statement that the boardroom’s new name reflects Inuit traditions.

“Inuit do not normally name inanimate objects after people; personal names are reserved for children in order to allow the name and spirit to live on,” Langille stated.

Tunnganarniq is an Inuit societal value “fostering good spirits by being open, welcoming and inclusive,” according to the Nunavut government’s website.

Ottawa police created the community equity council in 2018. The group includes community members, Indigenous elders and senior police members. According to its webpage, the group will “collaborate with the Ottawa Police Service to work more effectively with Indigenous, racialized and faith-based communities in Ottawa.”

For Pootoogook and her remarkable legacy in Indigenous art, the renaming joins a long list of groundbreaking accomplishments and honours. In February, Ottawa’s community and protective services committee approved naming the park next to the Sandy Hill Community Centre after the Nunavut-born artist, who was living in Ottawa when she died in 2016.

Although Annie died tragically in 2016, she left behind a legacy of Inuit art, of promoting her Inuit heritage, of showing our people who they are — the good and the bad.”

Gov.-Gen. Mary May Simon

The park renaming was officially celebrated on Nov. 7 at an event featuring Canada’s first Indigenous governor general, Mary May Simon, an Inuk from northern Quebec.

“Although Annie died tragically in 2016, she left behind a legacy of Inuit art, of promoting her Inuit heritage, of showing our people who they are — the good and the bad,” Simon said at the park ceremony.

She said Pootoogook’s art has enhanced the depiction of Inuit culture by “showing Canadians how we express our joy and our pain, our struggles and resilience, and how Inuit — like all Canadians — desire and deserve the same basic standards in life: respect, understanding, friendship, love and the opportunity to grow and thrive in a healthy, safe environment.”

Ottawa Art Gallery director Alexandra Badzak spoke at the police equity council committee meeting in September, offering her perspective on the artist’s impact.

“Those of us in the arts, in Ottawa, across Canada and internationally know of the importance of Annie Pootoogook’s work,” Badzak said. “(Pootoogook’s) pen and pencil crayon drawings drew upon the legacy of her famous artistic family, including her grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona, while making a pivotal shift in subject matter and aesthetics; with depictions of contemporary Inuit life, from a deeply personal perspective as a woman.”

Her representations of everyday Inuit life in the 21st century reconfigured conceptions of northern Indigenous art and earned the artist acclaim at galleries across the country.

Site Media Inc. co-founder Katherine Knight launched her film company in 2006 with a documentary about Pootoogook’s life. Initially, Knight said, she found Pootoogook’s work adventurous in its honesty. “We didn’t know her style when we started; it was an adventure discovering the work of an artist who was from Kinngait (in the South Baffin region) and who had such a different reality than ours,” Knight said over the phone. “So it was really just curiosity about a world that I had no background or knowledge of.”

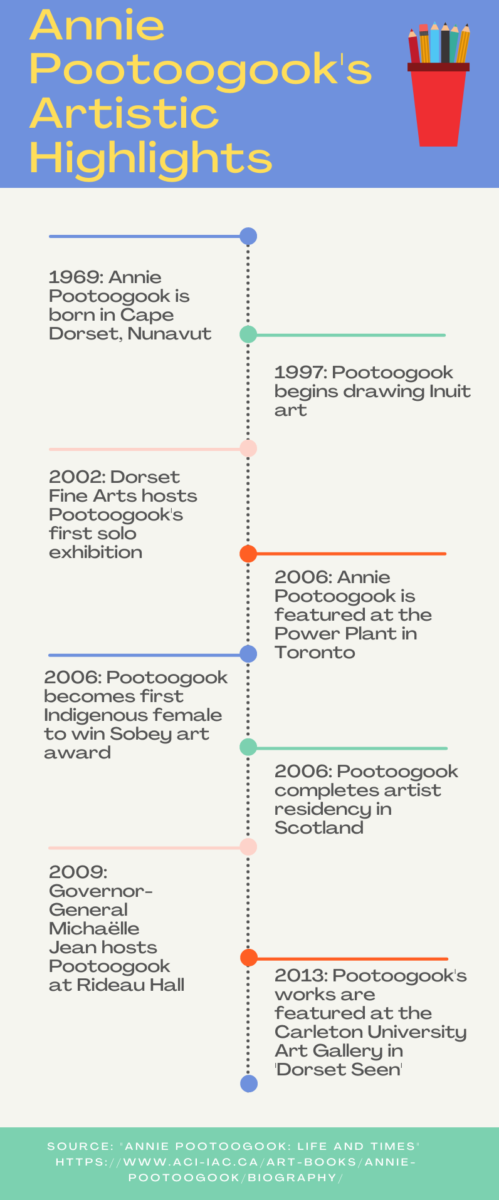

Recognition Pootoogook garnered for her visually captivating art ranged from an outstanding debut exhibition at Toronto gallery Dorset Fine Arts in 2002 to becoming the first female and first Indigenous artist to receive the coveted Sobey art award in 2006.

Pootoogook’s drawings focus on everyday aspects of life in Nunavut, from predominant symbols of Inuit culture like enjoying seal meat at home, to the more specific details of her experience growing up in Cape Dorset. Works such as “Coleman Stove with Robin Hood flour and tenderflake,” and “Cape Dorset Freezer” capture specific aspects of the local activities observed by Pootoogook, providing a modernized twist on traditional Inuit artistic depictions.

Pootoogook’s career took off in the mid-2000s, when the artist was also at her most prolific. A 2006 exhibition at The Power Plant gallery in Toronto and a residency spent drawing in Scotland the same year propelled Pootoogook to the forefront of art made in Canada.

Galleries and collectors appreciated her honest depictions of modern Inuit life. Ahead of their 2006 exhibition of Pootoogook’s work, The Power Plant wrote of Pootoogook, “Like her grandmother, Annie is a chronicler, and her drawings of domestic interiors and modern outpost camps reflect the disparate social, economic and physical realities of today’s Canadian North.”

Badzak added that Pootoogook “depicted what was valued and unique in her culture through the counterpoint of what was rapidly changing.”

Knight said naming parks and board rooms helps preserve Pootoogook’s name and legacy as an important Canadian artist.

“They ensure that she’s not forgotten and that a new generation of people come across her name and become curious about her and her legacy,” Knight said, adding: “Having things named in her honour puts her name front and centre and helps us remember her.”