At the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories in Chalk River, Ont., about 150 kilometres northwest of Ottawa on the banks of the Ottawa River, a new facility to dispose of nuclear waste is facing another round of scrutiny from concerned environmental groups including the Ottawa Riverkeeper.

Currently in the middle of its Environmental Assessment licensing proposal hearings, the near surface disposal facility (NSDF) will be an above-ground dump for low-level radioactive waste.

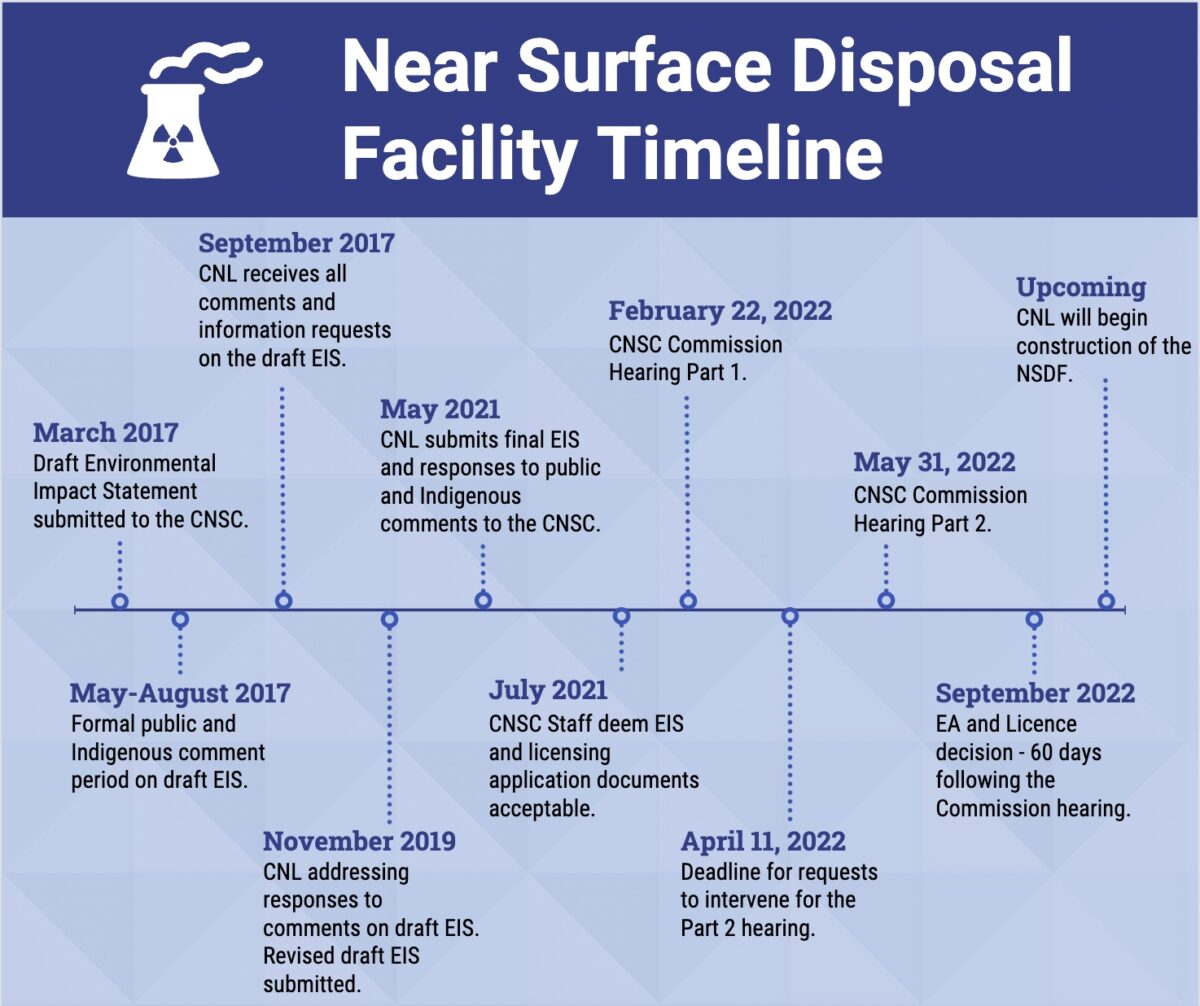

Initially proposed by CNL in March 2017, the licensing proposal for the NSDF was released in January. This follows a review of CNL’s environmental impact statement by staff with the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission in July. The CNSC staff review, according to a commission spokesperson, determined that CNL’s submission was complete and deemed acceptable for the preparation of a further environmental assessment report for the CNSC to consider in its decision-making process.

The first hearing took place Feb. 22 with submissions from CNSC and CNL staff. The second hearing is to take place on May 31 with comments from Indigenous communities and members of the public, including environmental protection advocates.

Dr. Ole Hendrickson is a long-time critic of CNL. In advance of the May hearing, the researcher with the Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County is preparing a document titled “Flaws, Errors and Omissions in the Case to Approve the Chalk River Mound” to detail his organization’s concerns.

“It’s got about 25 points in it now. We’re trying to keep it as succinct as possible … because you only get 10 minutes,” Hendrickson said.

Location, location, location

Among the key points, Hendrickson will raise is the siting of the facility on land near the Ottawa River.

“The facility is way too close to the river. The mound would deteriorate,” Hendrickson said. “It’s just crazy. It’s on a sloping hillside. It’s too small a site for the waste that’s been accumulated over the past 75 years.”

According to Sandra Faught, manager of environmental remediation management licensing support at CNL, the NSDF will be about 10 soccer fields in size. Describing it as a grassy mound, Faught said the facility is meant to be an important step in reducing risks to human and environmental health.

“The reason that we need the near surface disposal facility is that Chalk River labs have been operating since the 1940s,” Faught said. “Through our operations, scientific breakthroughs, production of medical isotopes and technologies to support our CANDU reactors, we have created waste.”

Endangered drinking water?

The Ottawa Riverkeeper shares many of Hendrickson’s concerns about the proximity of the NSDF to the Ottawa River. The local environmental advocacy group is compiling its concerns to bring to the upcoming public hearing, communications manager Matthew Brocklehurst said.

A blog post in February indicates one of the Riverkeeper’s major concerns pertains to the effluent from a wastewater treatment plant CNL is planning to build alongside the NSDF.

“The effluent from the plant will be discharged into Perch Lake at the Chalk River site, which eventually drains into the Ottawa River,” states the blog post. The Ottawa River is the main drinking water supply for Canada’s capital.

“Ottawa Riverkeeper has long had multiple concerns with the plans for the NSDF. As members of the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories’ Environmental Stewardship Council, we have learned a great deal about the Chalk River site, its operation, and the waste that has accumulated there,” the Riverkeeper blog post states. “We have also participated in multiple consultations about the project over the years. Some of our initial concerns have been taken into consideration in this most recent proposal, yet a number of questions remain.”

Faught said direct discharge into Perch Lake is a “secondary back-up” method that would only be used during high seasonal groundwater conditions. The primary discharge pathway will be through an exfiltration gallery, which Faught compared to a septic system, that would also eventually drain into the Ottawa River.

“We will store all the effluent that has been treated and test that effluent prior to any discharge to the environment,” Faught said. “We have established effluent discharge targets, so before any discharge to the environment, we will test it to make sure we meet those targets.”

Concerns at a federal level

In March, Natural Resources Canada released a new draft of its radioactive waste policy, which was open for public comment until April 2.

Ottawa Riverkeeper is concerned that this federal policy review is happening at the same time as the NSDF hearings.

“Projects like (the NSDF) are controversial in part because they are relying on old policy frameworks that Canadians clearly want updated,” the Riverkeeper noted in a March 17 blog post.

As Ottawa Riverkeeper and the Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County worked to prepare their comments for submission ahead of the May 31 round of hearings, Faught said she was feeling a little overwhelmed with preparations for the consultations.

“We almost feel like we’re training for sitting in a courtroom for two to three weeks,” Faught said. “It’s not just the science and technical stuff that you have to know, there will be emotions from our intervenors, both positive and negative.”

If all goes well, Faught said construction of the NSDF could begin in the fall. Even though the initial timeline of the project was extended by a few years due to high levels of public feedback, Faught said she’s happy to have had the input because it’s allowed the project to grow.

“We keep saying that this is a marathon,” said Faught. “It’s not a sprint.”