Mobile testing centres might not be part of Ottawa Public Health’s response to COVID-19 as a pilot program with satellite sites around the city comes to an end.

Nearly 1,000 people were tested in July at five locations across Ottawa identified as hotspots with clusters of cases. But the mobile tests conducted in those locations did not detect elevated rates of infection.

“Mobile/targeted testing remains an option that Ottawa Public Health may recommend as part of a health promotion approach in communities affected by COVID-19 in the future, but on its own it will not be a priority for rapid response to increased community transmission of COVID-19 in disproportionately affected neighbourhoods,” an OPH spokesperson said in an email.

This doesn’t mean testing isn’t a concern for OPH.

Dr. Vera Etches said Friday morning that more COVID-19 testing sites are coming to Ottawa. As well, the city’s chief medical officer of health, said people will soon be able to book appointments for a test.

There are three regular locations where residents can get tested: the assessment centre at Brewer Park Arena and two clinics on Moodie Drive and Heron Road, which provide testing as well as medical services, For Inuit in Ottawa, the Akausivik Inuit Family Health Team can also provide COVID-19 assessment and testing.

These locations can’t keep up with demand, Dr. Vera Etches, Ottawa’s medical officer of health, told the media Thursday. On three days this week, the testing centres swabbed more than 1,000 people — including one day when 1,278 tests were conducted, according to Ottawa Public Health data. Some people have waited as long as four hours for tests, according to The Ottawa Hospital. Demand for testing is expected to grow in the fall.

Also Friday, the prime minister announced the release of a new contact tracing app, called COVID Alert in Ontario. The app, which is used anonymously, can be downloaded to iPhones and Android devices. It will let the user know if they have been near someone with COVID-19.

Mobile clinic

The first mobile clinic at Ogilvie North Park in the former city of Gloucester was started after concerns had been raised about community members’ ability to access the city’s main testing facility at Brewer Park near Carleton University.

The Ogilvie clinic — a partnership between Ottawa ACORN, the Ottawa Hospital, the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre, the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa Inner City Health and the Ottawa Paramedic Service — tested 120 people on July 11.

Four more “pop up” centres were set up in residential communities across the city between July 16 and 19. The sites were chosen based on where data collected by OPH and the Champlain Health Region Incident Command suggested there was a higher-than-average number of cases.

“The rate of confirmed cases, sources of infection and socio-demographic characteristics of these clusters are considered when determining recommended sites for mobile testing,” OPH told CTV News Ottawa at the time.

“It is through this surveillance data that OPH and CHIRC identify the need for mobile testing service based on which communities would benefit most from testing in their community.”

Some 287 people were tested in the Craig Henry community in west-end Ottawa and 128 people were tested at a Heatherington location off Walkley Road in the southeast part of the city. Another 268 people were tested in south-end Heron Gate and 188 people were tested at a Prince of Wales Drive location southwest of Carleton.

Leigh Sleeth went to be tested at the Prince of Wales site.

Sleeth had spent the beginning of the pandemic in hospital recovering from an infected hip that had left her hospitalized for three months. During that time, she was tested for COVID-19 every three of four days.

Now back home, she uses a temporary wheelchair to move around, and mostly lives out of her bedroom.

She wasn’t sure, at first, whether she should get tested for the coronavirus at the city’s Brewer Park facility.

“Initially, I didn’t think I would because I thought I would be more exposed to people that might have it,” said Sleeth.

But when a mobile COVID-19 testing centre popped outside her apartment building on Prince of Wales Drive, she decided to take the test.

“Everyone was wearing masks and it was easy,” she said. “The people I talked to at the booth were so helpful.”

“Mobile/targeted testing remains an option … but on its own it will not be a priority for rapid response to increased community transmission of COVID-19 in disproportionately affected neighbourhoods.”

— Ottawa Public Health

Jean-Marc Ladouceur, a member of the community advocacy and anti-poverty organization ACORN, said the program had made a big difference to him and his neighbours.

“For people in my building, we have a lot of seniors, people with disabilities — for us to travel across the city is hard, it’s also financially draining,” he stated in an ACORN press release about the mobile clinics.

“I had a stroke three years ago so I can’t stand for too long, making standing in a line to get tested or standing on public transit to get there impossible,” he added. “It makes a big difference to have it right outside the building.”

Resurgent cases

In recent days, Ottawa has seen an uptick in cases, but Dr. Brent Moloughney, OPH’s associate medical officer of health, said results from the mobile testing facilities are not behind the resurgent number of positive cases.

“I know that some people have speculated that, ‘Oh, the jump in cases is due to this testing we did,’” Moloughney said in a recent media conference held over Zoom. “And the answer to that is no.”

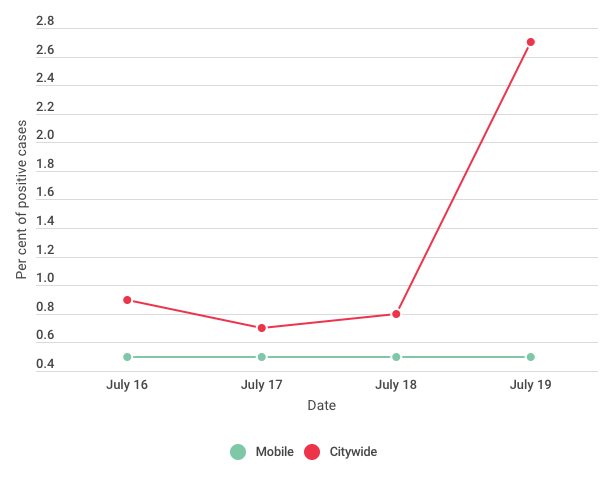

The mobile testing at the five locations resulted in very few positive tests — fewer than 0.5 per cent of all tests across the mobile sites – and no individual site had a significant number of positive tests, according to OPH.

In comparison, citywide testing returned positive results for COVID-19 at a higher rate than at the mobile testing centres,

The number of positive tests was lower than expected and was probably caused by some people not turning up for testing, according to the OPH statement.

“Deploying rapid mobile testing in disproportionately affected communities is not resulting in the detection of a large volume of new cases at the time of testing,” the statement said.

“This is likely due to barriers other than direct access to testing, such as COVID-19 not being perceived as a threat to health, individual recognition of the reasons/indications for testing, and concerns about how one will be viewed in their community if they present for testing at a mobile clinic.”

In the future, OPH said it would work more closely with communities to ensure people are aware of testing, “recognizing that mobile testing/targeted testing requires preparatory time and fulsome engagement of the community to be successful.”

[…] 7 hours ago 6 min read […]