As public hearings proceed on a Quebec bill designed to strengthen safeguards for the French language, First Nations leaders say the province is ignoring their demands for linguistic protection and proposing laws that would further threaten Indigenous cultures.

On Sept. 21, the first of nine special consultations and public hearings commenced in Quebec City on the controversial Bill 96, an act respecting French, the official and common language of Quebec.

The consultations on the bill have been marked by fiery testimony from those on all sides of the debate.

In addition to affirming French as the official language of Quebec, the bill makes several amendments to the provincial Charter of the French Language — notably, setting limits on the number of children receiving English-language education and imposing rules regarding appropriate knowledge of French in businesses and workplaces.

While some believe the overhaul of the charter promised by Premier François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec government doesn’t go far enough to “protect” French, others, including Anglophone Quebecers, Allophone Quebecers (those whose first language is neither French nor English), First Nations and Inuit, are pointing to the planned legislation’s discriminatory nature.

A ‘formal attack’ on First Nations’ language rights

The Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador, the regional organization grouping the 43 chiefs of the Quebec and Labrador region, says the bill would obstruct “the future and development of Indigenous communities”.

“Now they’re trying to say that their language is in jeopardy? I mean, welcome to my world… I hate to see anybody have any pain but you know, now (they’re) feeling what our communities and our First Nations have been going through for centuries.”

Grand Chief Victor Akwirente Bonspille of Kanesatake

On Sept. 28, the AFNQL released a 50-page document making nine recommendations and four proposed amendments to the bill. In addition to the group’s proposal for the government to acknowledge the right of First Nations and Inuit in Québec to teach and defend their language and culture of origin, the amendments would allow for Indigenous students to continue to study in their maternal and second language, and protect the language rights of any student living off-reserve.

“The Legault government’s Bill 96 is a formal attack on the constitutional language rights of First Nations,” said Ghislain Picard, Chief of the AFNQL, in a Sept. 2 press release.

The CAQ government leaders “get all worked up in the name of their so-called constitutional prerogatives and do not hesitate to use the Constitution Act of Canada for primarily electoral and partisan purposes. … However, when the time comes to respect the provisions of the same constitution that would allow justice to Indigenous Peoples, the rhetoric changes.”

Implications for Indigenous students

Chief John Martin of Gesgapegiag in Quebec’s Gaspé region, who heads the AFNQL’s education advocacy work, was alongside Picard on Sept. 28 at the committee meetings in the National Assembly. Delivering his speech in Miꞌkmaq, and connected to the meeting through video conference, Martin highlighted the implications of this bill for Indigenous youth.

“The message that we tried to put through was that the French language charter already caused problems for our communities for the past 40 years,” said Martin. “And, you know, (seeing the) ministers, and the premier saying that there’s not going to be any change (and that) it doesn’t affect us is rather concerning. … I don’t know how much of an impact we’re going to have on this government,” he said.

He said the major problem across the province over the past two decades is that Indigenous students are often pushed out of the public education system in Quebec.

After finishing school on-reserve, Martin says students often transfer to public high school systems, where they have to complete French courses to graduate.

“A very significant percentage of our students are not able to get their high school diploma because they can’t pass the French exam credits. So without their credits, they’re not able to get that diploma from the Minister of Education. … They’re not able to continue here in Quebec because the CEGEPS and the colleges require that you have your high school leaving from Quebec,” said Martin.

“(As a result) either they leave school permanently, they don’t go back to school, quit, drop out, whatever, (or), in other cases, they go elsewhere. They’ll go to New Brunswick. Sometimes it works out, sometimes it doesn’t.”

The proposed bill also affects language revitalization efforts for young people, said Martin — with kids having to put their own Indigenous language learning on the back burner to learn French and get through school.

“Priority becomes putting your efforts in a different language and not your own, and that's had quite an impact over the past 20-30 years,” said Martin. “This also has an impact on our students in terms of their perception of their language, themselves, and their community.”

It can even be described as a “language genocide” said Grand Chief Victor Akwirente Bonspille of Kanesatake. He noted that the proposed bill is hypocritical, especially considering the recent efforts across Canada towards reconciliation.

“It's being forced on us again — forced on everybody, not just First Nations but all Anglophones. ... This is going against everything that Canada and the province of Quebec has been pushing on us for reconciliation and understanding of our Indigenous rights,” said Bonspille.

“Now they're trying to say that their language is in jeopardy? I mean, welcome to my world. ... I hate to see anybody have any pain but you know, now (they’re) feeling what our communities and our First Nations have been going through for centuries. And we're still going through it and who's there to help us?

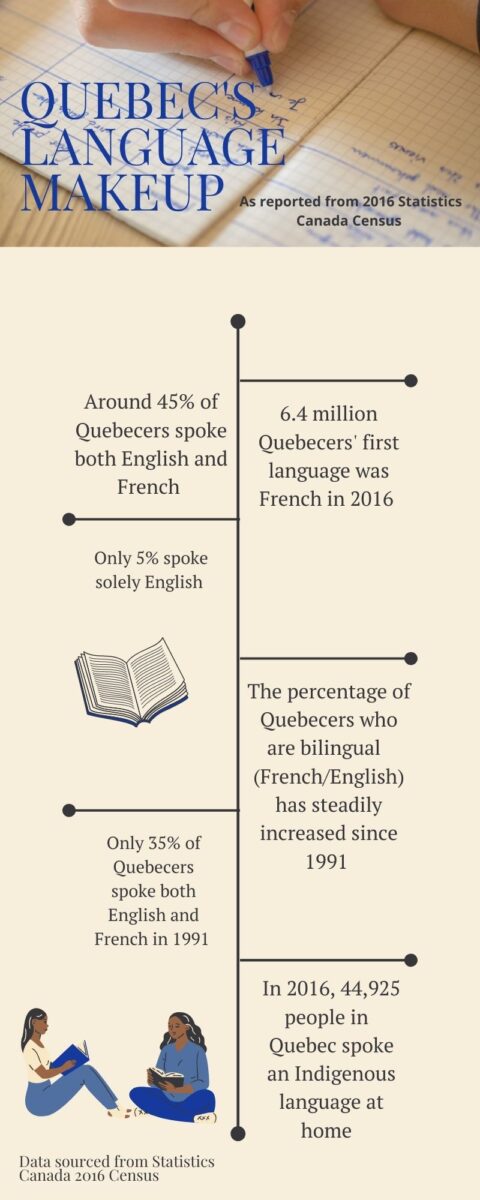

At the first committee sitting in Quebec City on Sept. 21, CAQ Justice Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette highlighted the “urgency” of this bill considering Quebec’s language makeup.

“The French language is losing ground in Quebec. It is a nation losing its strength,” said Jolin-Barrette. “The French language brings us together. It is the expression of our culture, our identity, our pride and above all, our nation.”

Seventy-three per cent of Quebecers agree that there is urgency to protect the French language in the province, according to the results of a survey on the language of the workplace and status of the French language recently conducted among 2,002 Quebecers who can speak French or English.

The survey, which was conducted by Léger for the labour organization La Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ), was released on Sept. 21. It found that only 29 per cent believe that favouring French as the language of work is discriminatory.

These results are not particularly surprising, said Matt Aronson, secretary of the Quebec Community Groups Network. He noted that the objective — protecting and promoting French — is not the problem. Rather, Aronson said the key issue for many Anglophones and Allophones is upholding this goal “at all costs."

“Somehow protecting the French language overrides our human rights, and makes it acceptable to do a wholesale suspension of the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. … That's the thing that we take objection to,” said Aronson. “People have been getting on just fine for 40 years. And it was a tough adjustment for many, many Anglophones and Allophones in Quebec, but we did what we needed to do. We've done the work, we came to the table, but to find out now that everything we've done is still not enough for the most extreme nationalists is disturbing.”

Linguistic minorities feel excluded

Aronson said the rhetoric that suggests Quebec identity is defined by the presence and acquisition of French is hurtful to anyone who identifies with the province but doesn't fit the “template of a Francophone Quebecer”.

“Be it that you’ve been here for five days or 500 years, we should be equal,” said Aronson, who is a fifth-generation Quebecer and a practicing lawyer in the province.

“We have the distinct impression we're not included in the CAQ’s definition of the nation of the Quebecois. But what more can we do? What more should we do to belong? The CAQ won't make the effort to ensure that everybody who chooses to make Quebec their home feels a belonging here. We feel that's not something that's being done accidentally.”

He said his hope for now is that “cooler heads prevail”, and the CAQ re-evaluates the way in which they promote the French language.

“We have the distinct impression we're not included in the CAQ’s definition of the "nation" of the Quebecois. But what more can we do? What more should we do to belong?"

Matt Aronson, secretary of the Quebec Community Groups Network

“The effort itself is probably going to do more damage to their cause, than it's going to assist them, said Aronson. "But you know, to be frank, I'm not entirely certain that they are actually doing anything other than a very cynical ploy towards re-election."

“They've read the tea leaves and said, ‘Well, our base wants more action on a bread and butter issue of identity’, and that's the French language . . . And what a shame, because there are so many more productive, interesting, progressive, useful things that the government could be doing with its time and energy.”

Rachel Watts, Thank you for this article, First Nations decry Impacts on their Languages, Quebec Bill 96. A month ago 23Sep’21 Our http://www.Indigene Community.info group (all humanity’s worldwide ‘indigenous’ (Latin ‘self-generating’ heritage) sent an email to the following Quebec Community Groups Network & government elected officials decrying Bill 96’s violation of 1st Nation sovereign & treaty language rights. Whether French, English or other immigrant languages, all our rights stem from our status as ‘guests’ of 1st Nations. As guests we could never violently usurp the sovereignty of our hosts, so in this sense having violated the 1st principle of immigration are still ‘on-parole’/’in-limbo’. Many 10s of millions of refugees fled from Europe’s failed economy & ecological destructive oligarch-run regimes. Endless war, economic-poverty & ecological devastation had implanted since the Assyrian, Greek & Roman ‘exogenous’ (L ‘other-generated’) invasions of once sovereign Celtic & Slavic ‘indigenous’ Europe. Yet in ongoing submission to Oligarchs who were exporting this failure worldwide, Europeans violently implanted the same failure in the Americas & worldwide. The vast majority of ‘settlers’ having forgotten or had our memories institutionally erased about our own indigenous laws & customs of peace & prosperity violently colluded in the imposition of this violent failure. The QCGN & all people of Quebec, should understand that its & our priority must be standing up for 1st Nation Restitution, Compensation & Reconciliation, because when indigenous laws & customs are reaffirmed, then we today & all future generations receive a sustainable peaceful future. 70% of Quebecers have 1st Nation blood. 85% of 1st Nations have blood from around the world. We are all one people in need of our kind & prosperous indigenous heritage. Email Sent 23Sep’21 STANDING IN PRIORITY LANGUAGE & CULTURAL SOLIDARITY WITH 1ST NATIONS. BILL 96 Open Letter to Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette from president Marlene Jennings + Matt Aronson’s excellent CBC Radio-Noon public discussion

To: “Rita.Legault@qcgn.ca” , “info@qcgn.ca” , “matt.aronson@qcgn.ca” , “Gregory.Kelley.JACA@assnat.qc.ca” , “Helene.David.MABO@assnat.qc.ca” , “francis.scarpaleggia@parl.gc.ca” , “Anju.Dhillon@parl.gc.ca”

In solidarity, we are one,

Douglas Jack, President of the Sustainable Development Association (Canadian non-profit since 1994) & its sub-chaptre Indigene Community (1983)