In February 2010, I was a high school student looking forward to the morning announcements. It was Black History Month, and stories of Black historical figures were regularly told over the intercom.

I was excited.

I always enjoyed learning about these figures, their sacrifices, their contributions to the lives of people like me and many others.

Unfortunately, we never heard more than two of these stories each week. By the end of the month, we had learned little about Black history — the number of figures mentioned never reached double digits.

By 2012 — my senior year — I realized that we learned about the same people and events every February without any additions.

It was like my high school was playing the “Greatest Hits” of Black history, and thought that was good enough.

I recently discussed this with some of my Twitter followers, all of whom went to school in Canada and had similar experiences.

It has gotten to the point where Daniel Afolabi, a student at the University of British Columbia originally from Alberta, started an online petition demanding more Black history be taught in all Alberta schools.

Afolabi’s petition has already received more than 26,000 signatures, including mine.

While I will never get tired of hearing about the contributions made by Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King Jr. in the struggle for equality, it’s frustrating to know that my school did the bare minimum to celebrate Black History Month, despite the number of Black students.

What’s more is that these stories are only taught once a year, and even then lessons are shallow, cursory. My history classes glossed over Black history in favour of Jacques Cartier’s voyages — again — or the study of how Parliament works.

I recently wrote an article about what it’s like being Black in Carleton University’s Master of Journalism program and one of the things I mentioned is that we should learn more about Black journalists and race-related issues.

A similar change is needed in all Canadian schools, where Black history continues to be swept under the rug. The idea that this is an “American thing” shouldn’t be an acceptable excuse.

Canada has hundreds of years of Black history, both good and bad.

Will adding more Black history to the curriculum solve racism and inequality in Canada? Not on its own. But it can help foster an understanding and appreciation in Canadian students while they are young enough to learn, steering them away from prejudice.

What many people don’t know — probably due to the shortcomings of the current curriculum — is that Canada does have an extensive Black history. Slavery was prominent in New France and British North America before it was abolished in 1834. Even then, some freed slaves were still forced to work for former masters as indentured servants.

Did you know that the 1910 Immigration Act prevented immigrants from entering the country if they were deemed “undesirable” or “unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada?” As a result of this discriminatory law, few Black people immigrated to Canada while it was in effect.

Just as Canada’s racist past should not be ignored by the education system, it is also important to learn about the contributions of Black Canadians to the history of our nation.

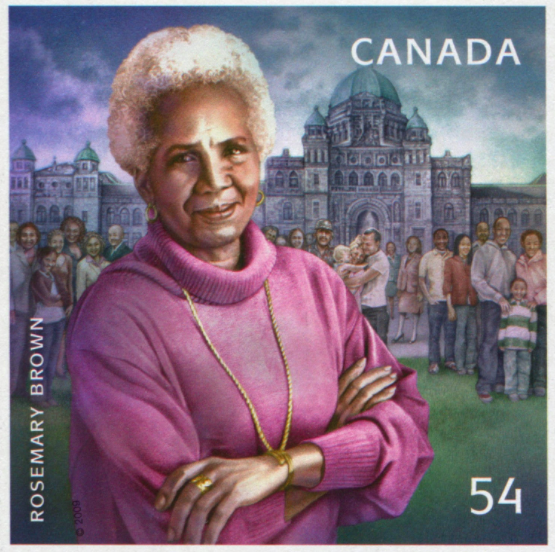

They should learn about Rosemary Brown, the first Black woman elected to a provincial legislature and to run for the leadership of a federal political party in Canada.

They should learn that Black Canadians continue to make history today, with TSN’s Kayla Grey becoming the first Black woman to “host a flagship sports-highlight show in Canada” in 2018.

The list of these stories goes on, a sign that they belong within the standard Canadian curriculum. If we want equality for all, we need to confront history as it happened, even if it might make us uncomfortable.

If you felt uncomfortable reading anything I wrote, I want you seek out similar pieces.

If this is your first peek at Canada’s Black history — the good and the bad — then I want you to continue learning about it, especially if it makes you uncomfortable.

Being uncomfortable isn’t a bad thing.

Discomfort leads to change and if that’s what it takes to get Canadian schools to teach Black history, then it’s worth it.