Western University’s O-Week orientation celebration closed on a disturbing note.

Tweets, messages, TikToks and Instagram stories flooded in on Sept. 13, recounting what students described as horrific sexual assaults and violence committed on campus during what was supposed to be a celebratory weekend.

More than 30 women were said to have been drugged and an unknown number raped in the Medway-Sydenham Hall co-ed residence on campus, which houses more than 600 students. The news came alongside reports of the death of a first-year student, Gabriel Neil, who was assaulted at 2 a.m. on Sept. 11 next to the school’s TD Stadium. Neil later died in hospital.

London Police are investigating his death, and, following a public outcry, have announced an investigation into the reports of sexual assault. The force has encouraged victimized students to come forward.

“The London Police Service is aware of information circulating on social media pertaining to a number of sexual assaults alleged to have occurred at Medway-Sydenham Hall over this past weekend. As of this time, we have not received any reports from this weekend involving incidents at Medway-Sydenham Hall,” the police statement said.

“Two reports were received in the week prior pertaining to allegations of sexual assault occurring at other locations on campus,” the statement added. “These incidents remain under investigation, and part of that investigation will include examining possible linkages to any unreported incidents.”

Those reports of sexual assault at other campus locations involved four female students.

Concern about campus safety has soared at universities and colleges across Ontario and beyond. In addition to the distress over young women’s safety in particular, some students are pointing to the larger issue of female victimization and “bro culture” that plague campuses across Canada.

Reports of sexual violence are not isolated incidents

What happened at Western is not an isolated incident, said Joshua Bell, a McMaster University student who organized a Change.org petition urging the Ontario government to investigate Western University. As of Sept. 28, it had garnered more than 22,000 signatures.

“There’s an overwhelming amount of support for the petition and for its goals, but also an overwhelming amount of support to get the (Ontario Ministry of Colleges and Universities) to step in to look into why these policies failed, and why the universities were unable to secure their part in protecting their students,” said Bell.

“I’m hoping that it kind of starts a domino effect with all the other universities and colleges in Ontario… to ensure that something like that doesn’t happen (again). It could have just as easily been my campus or another friend’s campus.”

Western acknowledges “culture problem”

In response, on Sept. 16, Western announced a new student safety action plan to introduce new security measures, enhance security patrols, hire new special constables and implement mandatory in-person sexual violence awareness and prevention training for all students in residence.

Western has also committed to implementing a new task force on sexual violence and student safety to “better understand and eradicate sexual violence”.

“This has been a tremendously difficult time for our students and the entire Western community. We clearly have a culture problem that we need to address. We let our students and their families down,” said university president Alan Shepard in a media release on Sept. 16 . “The measures announced today are the first step in a journey to deeply examine the prevailing culture on our campus.”

The mere acknowledgement of the “culture problem” is a step in the right direction, noted Michael Kehler, research professor in masculinities’ studies at the University of Calgary.

However, he noted the university administration initially responded by offering up statements that sought to “confirm” and “clarify” the situation, days after the initial reports of sexual violence.

“That was a really troubling part of this narrative that I would suggest the university failed miserably on, in terms of referring to ‘rumors’ and ‘allegations’,” said Kehler. “The university initially was trying to manage (this) internally… that was really damaging to the relationship that the administration established.”

Lack of trust

The fact that students and young women felt as though they could only share their stories on social media is a case-in-point of how institutions continually fail to build a relationship of trust with students, particularly young women, noted Kehler. He said there need to be more conversations as to why the relationship has failed, and how to rebuild.

It boils down to the fact that institutions, particularly universities, historically, have not taken reports seriously, said Kehler, pointing to the need for a better and safer way for women to be able to talk and “not fear repercussions, not fear not being believed.”

It’s a gap Carleton University’s Sexual Assault Support Centre is trying to fill. Kristina Epifano, the co-ordinator of the centre, acknowledged the “taboo” associated with sexual violence.

“A lot of people don’t talk about it,” says Epifano. “They don’t talk about safe sex and they don’t talk about what consent looks like in practice. … In practice it looks so different.”

According to a 2019 sexual violence survey published by the Student Voices, 89 per cent of Carleton students who participated in the survey said they had a good understanding of consent and what it looks like. However, 67 per cent of students said they experienced unwanted sexual harassment and 26 per cent said they had been sexually assaulted.

“Clearly there’s a disconnect. If people are saying, ‘Yeah, I understand consent,’ then how come our numbers of sexual violence are still so high?” said Epifano.

Education needed

“The only way that we can have a shift in the culture is if it is an institution-wide priority,” said Epifano.“We really need to have that conversation, the fact that ‘no means no’."

Carleton University’s Womxn’s Centre has also identified the immediate need for better training and sexual assault support programming in universities.

“When such a public event like that happens, it probably brought up those feelings of fear and some people may have felt re-victimized, like they were living through what happened to them (again),” said Khan. “So we want to have these resources out there and available as soon as possible.”

“It's not that they're happening just in London or in Guelph,” added Derman. “You should be able to be on residence and feel safe.”

Despite comprehensive prevention services, Charlene Senn — Canada Research Chair in Sexual Violence and professor of psychology and women’s studies at the University of Windsor — noted that sexual violence against adults has not decreased.

Rather, she said, after decades of national and international work on the matter, the rates of violence and attitudes which have become normalized remain pervasive. This, she said, has an impact on how, and to whom, victims disclose their experiences.

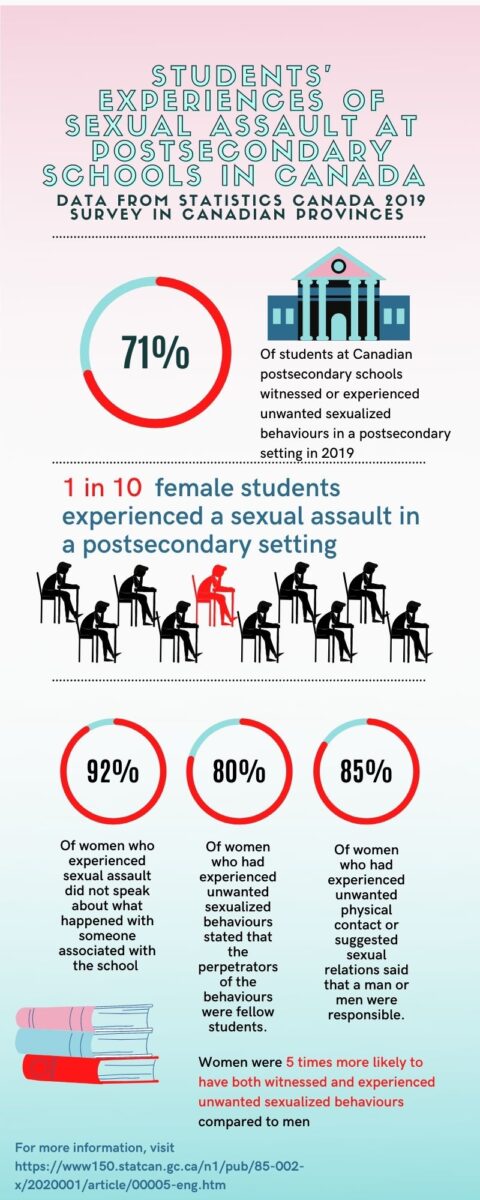

Only eight per cent of women who experienced sexual assault spoke about what happened with someone associated with the school, a Statistics Canada survey on students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in Canada found.

The data also showed only 54 per cent of female students agree their school would handle a sexual violence complaint fairly.

“We want to increase trust so that they can disclose to friends, family and trusted people on campus, so that they can get the maximum amount of support and actual things like accommodations on assignments, and making sure that they're safe,” said Senn.

She noted that increasing trust among victims also starts by effectively formulating sensitive public statements following news of violence — statements that call upon sexual violence support experts and data.

“That is one of those strange things where universities are still very concerned about their public image, and that inadvertently then makes them take PR approaches, rather than deep intellectual (approaches), looking at the expertise that exists around sexual violence on campus,” said Senn.

Rethinking campus culture

That is why universities should be taking notes, added Bell, something he notes was lacking in response to the incidents at Western.

“It's only really been Western that we've been hearing from; all the other universities and colleges have kind of remained silent on this issue,” said Bell. “I think that sends a large message to members of the public and to survivors, as well, that it’s not high on their agenda to deal with things like this.”

If other universities are not taking close notes, it is at their peril, said Kehler.

“This is not just a problem at Western," he stated. "Western suggested that they've got policies in place that connect to what the Ontario government said needs to be done, (but) that's not enough. Policies are one thing, practices are quite another.”

He noted that rather than policing, or imposing surveillance tactics on campus, there is a need to change the “cultural understandings,” to shift what is acceptable, and move away from the high levels of “bro culture", “machismo” and “heterosexism” that is quite common across universities.

“This is about being courageous enough to rethink what those power relationships with other people can mean. And I think that's a very difficult part for some men,” said Kehler. “But you know . . . I felt heartened by the fact that there was such a mobilization of voices.”

I attended UWO in 1989-1990 and there was already a heightened level of awareness surrounding the risks female students faced when sinply walking alone around campus so please forgive me if I’m skeptical that merely acknowledging the “culture problem” is a step in the right direction. They did exactly that 30 years ago and yet here we are all over again.