When 35-year-old Simon Graff wakes up in the morning, he has two wardrobes to choose from: the one in his closet or the one on his phone.

From shoes on fire to a golden hoodie, Graff has been buying digital clothes since September 2020. But what does this actually mean?

Using websites such as DressX, he purchases a 3D file of whatever article is available — let’s say a T-shirt — and simultaneously uploads a pre-taken photo of himself posing in a way that would flatter the shirt. From that, the photo will be altered by a professional and sent his way a couple days later, featuring the top he purchased being worn on his body. If he’s unhappy with how it looks, he can tell the photo editor and further alterations can be made.

Then, on his social media channels, Graff starts sharing a picture of himself wearing the shirt he’s never actually worn.

Though it may seem like something straight out of the dystopian British TV show, Black Mirror, virtual fashion is real and existed before it started showing up on social media feeds. Matthew Drinkwater, head of the Fashion Innovation Agency at the London College of Fashion, pointed out how the video game industry has made millions from selling digital items with which players can dress up their avatars.

“The gaming industry represents the perfect example of how people are paying real money for digital clothes,” said Drinkwater. Fortnite fans in particular have been known to spend more than $50 million collectively on a set of character skins, so it’s not entirely outlandish to imagine this translating easily to one’s own digital persona. Drinkwater added that this is especially relevant with people spending more time online in the last year due to the pandemic.

“You’ve got all of these forces of the technology getting better, people spending more time in virtual spaces, becoming more comfortable conversing about digital experiences,” he said. Those things “got us to a point where people started to spend really significant amounts on digital products.”

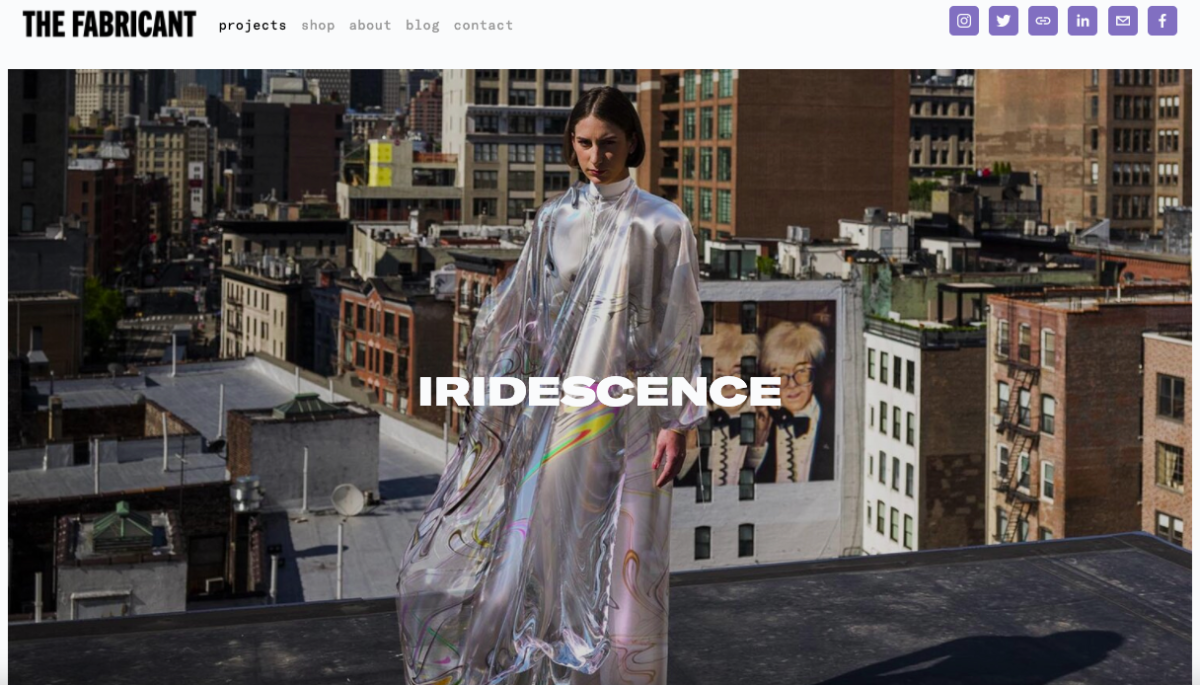

The first digital-only dress, “Iridescence,” designed by Amsterdam-based virtual fashion house The Fabricant, sold for $9,500 in May 2019 at a charity auction in New York. It’s now clear there’s potential for businesses and designers to make big bucks with the concept. It also allows smaller 3D graphic designers to have their work purchased on a much grander scale.

Pepe Castelo, The Fabricant’s digital trade co-ordinator, said one of the main goals of digitizing the fashion world is to make it as fair as possible.

“We don’t want one person to have the control over everything,” said Castelo. “We know that there’s going to be one, two or three big players building it … and we want to make sure that’s democratic.”

He added that The Fabricant has released “frops” — short for “free file drops” — on the company’s website to encourage newcomers to try their products at no cost.

“We engage a lot with the community. We want to work with them on how to use the files (and) different software,” he said. “We really believe in co-creation, and we are sure that this place needs to be built. We call it the wardrobe of the metaverse.”

Despite the price for Iridescence, some designs on DressX cost as little as $20 US each. However, purchasers can only have products edited onto one photo at a time. If they’d like to wear the piece in several different photos, they’ll have to pay for each one.

If purchasing directly from The Fabricant instead of through DressX, consumers will need to figure out how to edit the file onto their own photos. This is one of many “cons” people are discussing online, including the general distaste for becoming too fixated on one’s social media presence.

“All I have to say is that I don’t exist online, but in real life,” said one Reddit user on a forum discussing digital fashion. Others are questioning if the people behind digital fashion are trying to replace physical products.

While the concept won’t be for everyone, that’s “completely fine,” said Drinkwater. He added that the objective isn’t to replace “real” clothing, but to offer an alternative since the industry “already produces too (many) physical products to consume.”

Graff pointed out that not only can it be an alternative for people who wish to avoid filling their closets with clothes they’ll only wear for an Instagram photo anyway, but it’s an opportunity for “designers (to) unleash their creativity to create fashion that goes beyond any limitations.”

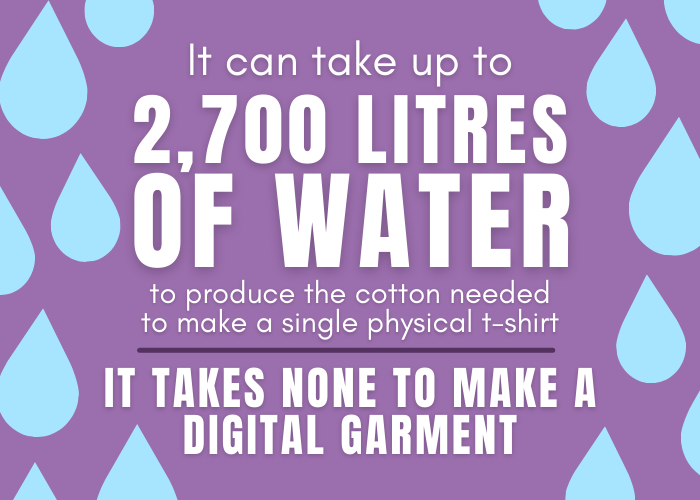

“Virtual fashion is an amazing option to express one’s individuality, without creating a negative impact on the environment,” said Graff. “(It’s) a relatively sustainable topic and hits the Zeitgeist quite well, I think.”

DressX claims the same, saying on its website that the company is “creating the garments of the future that eliminate waste and chemicals during production, and minimize carbon footprint.” According to DressX, the production of a digital garment emits 97 per cent less CO2 than the production of a physical one. While materials such as polyester can take up to 200 years to decompose, getting rid of a digital file is as easy as clicking “delete.”

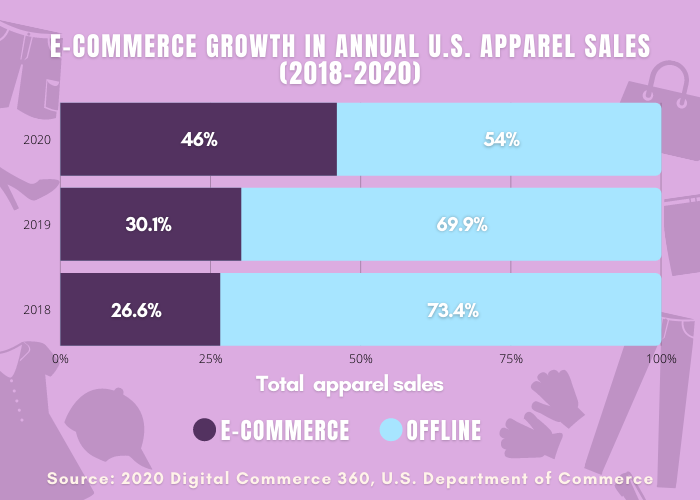

Graphic by Miranda Caley. (Sources: World Wildlife Foundation and DressX’s 2020 Digital Fashion Sustainability Report.)

With the world becoming more digital than ever, Graff, who has worked in immersive media and tech since 2014, said he’s expecting to see more virtual clothing appearing on social media feeds in the future.

“I honestly think that virtual fashion will be disruptive at first, becoming a new standard for the fashion industry shortly after, maybe even a strong industry (on) its own,” said Graff. “It’ll be crucial for fashion brands to take this development seriously to succeed in the future.”

And some companies already have. High-end brands such as Gucci and Moschino have collaborated with video games like Roblox and The Sims to give players access to designer clothing they otherwise may not be able to afford in “real life.” According to Castelo, the future of virtual fashion will hopefully involve the ability to wear digital purchases on multiple platforms.

“You would have the NFT of a T-shirt, be able to take it into DressX and wear it on a picture, but you will (also) be able to take it into Snapchat and wear it in AR (augmented reality). Then you will also be able to take it into any game and wear it (there),” said Castelo.

An NFT is a non-fungible token, a unique digital purchase typically collected by those familiar with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

Though it’s far into the future, Drinkwater said he expects that one day we will be able to see digital fashion right in front of us, in real time.

“I could hold up a device, whether it be a phone, whether it be a pair of glasses … I could look around and see people wearing digital elements,” said Drinkwater. “I think until about 18 months ago people still felt like that was a bit of a stretch, but the advent of NFTs underpinned by cryptocurrency has become a demonstrator for people paying really serious money for digital products.”

Graff agreed, saying that the emergence of new tech, like AR smart glasses, will make the “everyday digitally boosted expression of our looks and individuality a new norm.

“It will take some time,” said Graff, “but I think, looking deeper, many of these behaviours are already expressed on social media in the form of filters and retouched imagery.”