In the wake of high-profile reports of sexual assaults at Western University in September, which drew nationwide headlines and prompted calls for action on campuses across Canada, survivors and activists at Carleton University decided changes were needed on the Ottawa campus, too.

While London, Ontario police have not been able to substantiate reports of 30 drug-related sexual assaults at a Western University residence, they acknowledged in October that victims don’t always come forward immediately, that sexual assaults are frequently left unreported and that they intend to keep the investigation open.

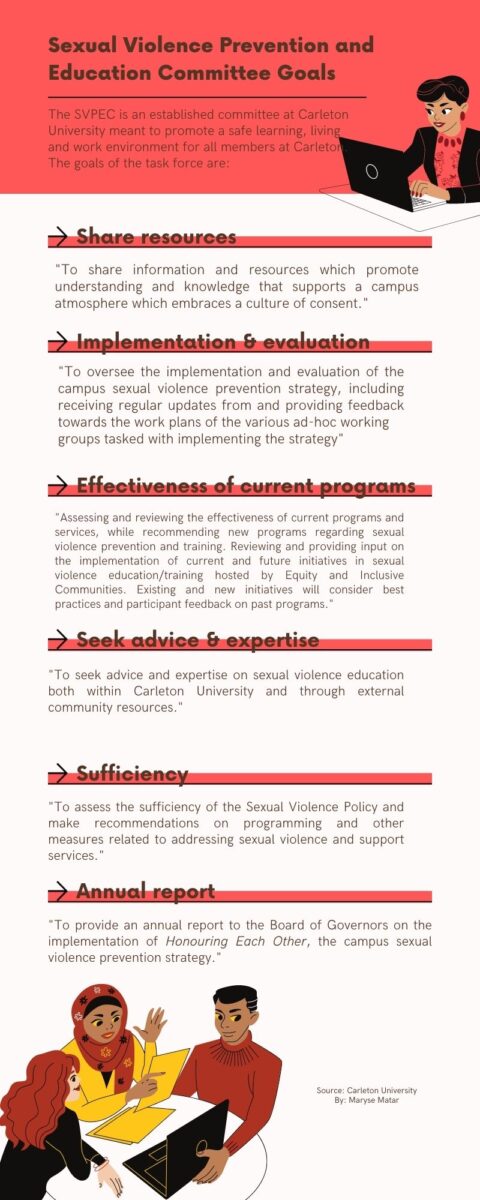

Carleton, like other post-secondary institutions in Ontario, is undertaking a mandatory review of its policies around sexual violence on campus. The review is to be completed by April 25.

“It is always important for the universities to have their policies updated,” said Valentina Vera Gonzalez, vice-president of student issues with the Carleton University Students’ Association.

Carleton’s current sexual violence policy states that the university is committed to maintaining a positive learning, working, and living environment in which sexual violence will not be tolerated and where reported assaults will be treated with seriousness.

The policy outlines the university’s commitment to addressing sexual violence, to providing support and services, to ensure follow-up once a report is made and to provide information about the process of responding to incidents of sexual violence.

The impact of sexual violence is evident in the stories of survivors.

A Carleton University student identified only as Minah is a survivor of sexual assault. In 2018, Minah reported the assault to the university’s equity services office but says the investigation didn’t begin until a month later.

Minah says she was not kept informed of the steps the university and her lawyer — appointed by Carleton — were taking.

“It felt like it was taking away my power. I had this fear. I thought the investigation was supposed to be helping me and I felt like it just made me feel less powerful,” she said.

Minah said accommodations were made to ensure her continued success academically. The university provided her with extensions and created schedules for her and the perpetrator of the assault so they would not cross paths in the university cafeteria.

Despite these steps, Minah said the procedures were not properly upheld as she continued to see the perpetrator around campus. By the time security arrived, she was already stressed and worried.

She said she believes security did not act quickly or thoroughly enough.

“I was scared to see them in the tunnels or see them outside, or even in the same building,” she said.

After the investigation concluded in the spring of 2019, Minah took a course on sexual assault resistance and awareness. She says the people that should be learning about the subject were not the ones taking the course.

“Why am I sitting here learning about sexual assault? I’ve been through it and I know what it is like. The people who should be learning about it aren’t here,” she said. “The people who would voluntarily go there aren’t the type of guys who would do this.”

Campuses are places where students are engaged with academic and social activities, but they are also places where women face sexual assault and harassment from the first day they step on campus.

Many on-campus sexual assaults happen in the first eight weeks of classes, according to a factsheet created by the Ontario branch of the Canadian Federation of Students.

One survey cited by the CFS-Ontario factsheet stated that “60 per cent of Canadian college-aged males indicated that they would commit sexual assault if they were certain that they wouldn’t get caught.”

Tiana Thomas, a fourth-year student at Carleton and an activist on campus, said that “a new policy should not only include better support for … survivors of sexual violence, but actually use methods such as education and awareness to actually prevent sexual violence from ever occurring.”

Thomas’ fight began during the fall semester where she learned of the reports of 30 women being sexually assaulted during the first week of fall orientation at Western University. She says what really drove her was the lack of public reaction.

“It has become so normalized that people are like, ‘Oh this is just the way that life is’,” she said.

According to a 2018 survey commissioned by the Ontario government, 59 per cent of Carleton University students reported they did not know where or how to access resources regarding sexual harassment and violence.

Thomas’ main concern is that universities no longer properly address the issue. She says she believes there is an urgent need to focus on prevention, education, resource accessibility and awareness.

“We have a Sexual Assault Support Centre and we have Health and Counselling Services, but those are for cases of sexual violence that have already taken place,” she said.

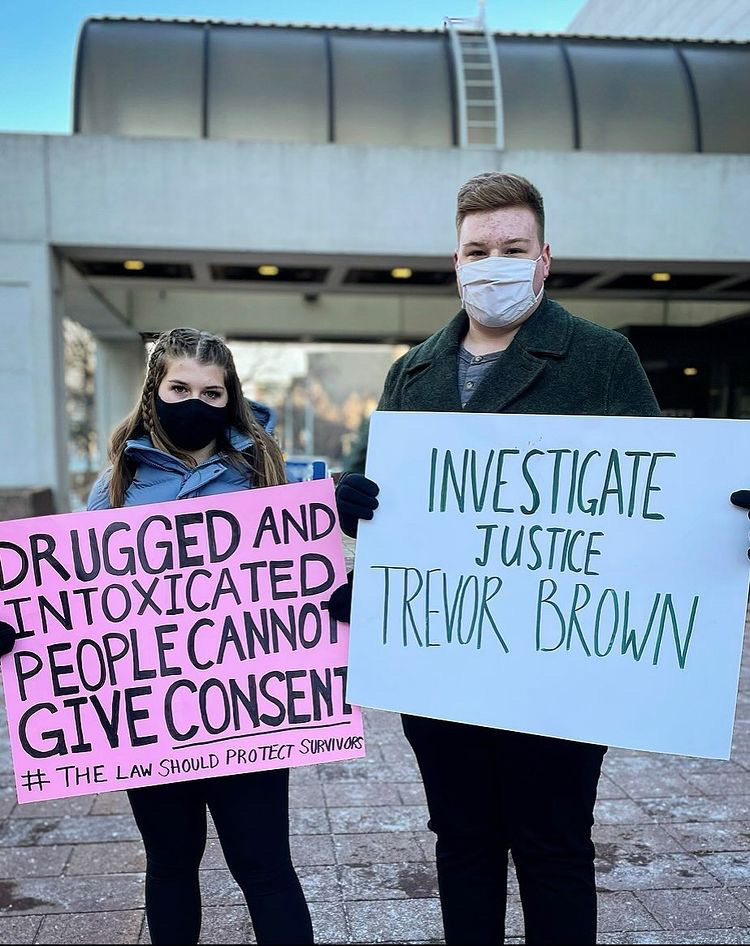

In response to this growing need for preventative measures, Thomas, alongside fellow student Anthony Valenti, published a call-to-action, addressing CUSA, the RRRA residence association, Carleton’s president and director of health and counselling services.

They proposed conducting an environmental scan, improving education and awareness, increasing training, new and improved resources, setting new standards of safety and instituting a zero-tolerance policy.

In 2018, the annual Sexual Violence Policy reports released by the Office of the Vice President showed that no consent education took place in that year, said Thomas.

“We need to not just make education available and voluntary, but mandatory,” said Thomas.

Gonzalez says education is key, adding there is a lack of training in place to prevent incidents from happening. Collaboration and consultations with students on the redrafting of the university’s sexual violence policies are to begin this month, she said.

Consultations will allow students to represent themselves and ensure that they are involved in the conversation about what the university is going to strengthen policies, said Gonzalez.

“Our role is really to represent all students so we want to … make sure that we’re able to get the word out and bring [as] many students as possible to these consultations to give them the platform to talk about what they care about and more with such an important topic like his sexual violence,” she says.

These consultations are closed sessions, confidential, and include a variety of consultation spaces — the Women’s Centre, Residence Service Centre, and the Indigenous Service Centre.

Gonzalez said it’s important that the university take an intersectional and multilayered approach to the review.

Consent, toxic masculinity, and rape culture are all concepts used to describe instances of sexual violence, yet the current policy’s vague language addresses the mere surface of these issues, Thomas says.

“I am not afraid to say that toxic masculinity and rape culture are very prominent at Carleton,” said Thomas.

She said that during her first year on campus, there were instances where she would hear men compete for women, and make bets on who could sleep with the most girls on campus.

“How could we possibly let this happen?” she said.

Gonzalez said these issues are extremely important and have a great impact on policies.

But, she added, to deal with these concerns there needs to be an effective policy to confront these concerns.

“The thing about sexual violence policy is that it sounds fantastic, but we need to ask ourselves, does it really work? Is it really effective?” said Thomas.

Under the university’s last sexual violence policy, many fell between the cracks, said Thomas.

Although student organizations, activists, and government bodies have forced Carleton into action, Thomas said Carleton is still failing to address the issue head-on.

“It means taking responsibility … that there was an issue going on at the university,” she said.

Thomas is working and collaborating with CUSA ahead of Sexual Violence Awareness Week Jan. 24-28. Thomas said she is preparing a safety tip sheet to use cellphones to protect people in emergency situations involving sexual violence or a potential assault.

She said she is also hosting an art exhibition during that week as a way to connect with survivors and their experiences.

Thomas said whether students think they’re going to be listened to or not, it’s important to play an active role, to send emails and to voice their opinions.

“It will go a long way,” she said. “I really want to encourage (students) to do that.”

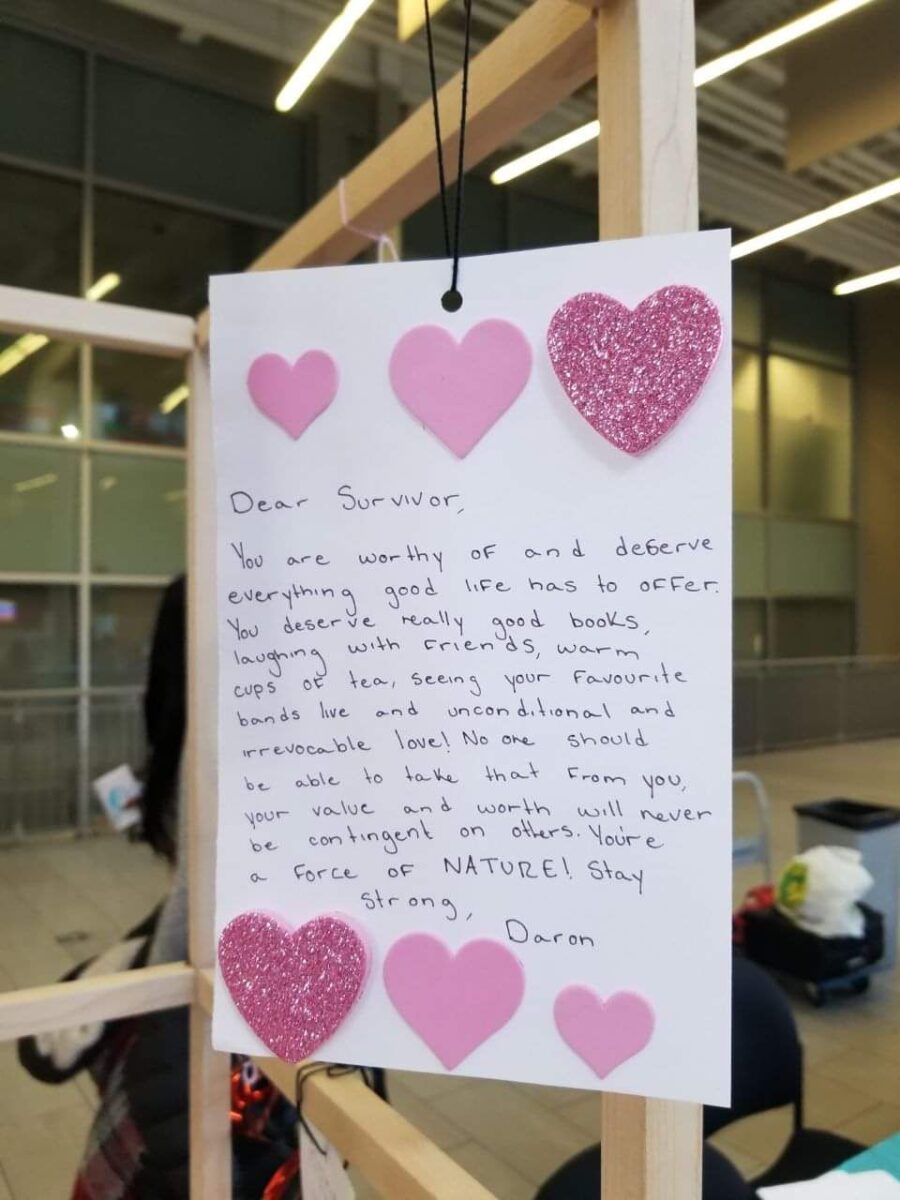

Even through small acts of kindness and gestures, students can play a critical role when it comes to helping survivors, she noted.

The proof of that statement can be found in Minah’s story.

Walking around campus, Minah stumbled on a table for survivors of sexual violence. The table had tools and string to create caring letters and notes. These public displays helped her cope, she says.

“I remember reading one of them. It made me cry, and it really helped me,” said Minah.

Resources:

- If you or anyone you know have experience sexual assault and are in immediate danger call 911.

- Campus Safety emergency number:

- (613) 520-4444

- Sexual Assault Support Centre:

- (613) 520-5622

- CUSA’s Wellness Centre:

- https://www.cusaonline.ca/who-we-are/service-centres/wellness/

- wellness@cusaonline.ca

- (613) 520-2600 x 8238

- Ottawa Rape Crisis Centre

- 24/7 crisis line: 613-562-2333

- Office line: 613-562-2334

- http://www.orcc.net/

- Sexual Assault Support Centre of Ottawa

- 24/7 crisis line: 613-234-2266

- http://www.sascottawa.com/

- Minwaashin Lodge for Aboriginal Women

- Crisis line: 613-789-1141

- http://www.minlodge.com/

- Men & Healing

- 613-482-9363

- http://www.menandhealing.ca/

- Ottawa Victim Services

- 613-238-2762

- http://www.ovs-svo.com/