Housing and homelessness has become a key concern for Canadians in all regions and that means the political parties are trumpeting their pitches heading into the Sept. 20 federal election.

Each party addresses the issues in different ways, from taxes, to “fast-start funds”, to residential ownership registries, to new formulas for “affordable” housing.

Regardless of which party wins, however, housing and homelessness must be a priority for the next federal government, advocates say.

“I think that the feds have a responsibility to get back in the housing game in a serious way,” said Kaite Burkholder Harris, executive director of Alliance to End Homelessness Ottawa.

“Housing is not featured or thought of as a human right,” said Burkholder Harris – instead, it’s often viewed in policy as an investment opportunity.

However, when people are safely housed, they require fewer emergency resources like health care and policing, she said.

“I think you’re hard-pressed to find an issue that has more of an economic impact in getting people stabilized and reducing the cost of other significant services in our communities than housing,” said Burkholder Harris.

A top consideration for Ottawa voters

Carolyn Whitzman agrees that housing is a top priority.

“At the most extreme level, COVID has really shown that housing is a matter of life and death,” said Whitzman, a professor of urban planning and housing researcher at uOttawa.

The pandemic has exposed housing disparities and highlighted the importance of housing, said Whitzman. Neighbourhoods where people are overcrowded often saw disproportionately more cases of COVID-19. And homeless people were concerned about staying in packed shelters, leading many to prefer living in outdoor encampments or informal settlements in parks.

While action is needed by all three levels of government, said Whitzman, “the federal government has a big role to play.

“In cities like Ottawa, there’s a lot of federal land around Tunney’s Pasture, around LeBreton Flats, that can and should be released for affordable housing.”

According to Ottawa ACORN, for every affordable housing unit that’s built, the city loses seven units to reno-victions and demo-victions, when property managers require tenants to leave their homes for renovations or demolitions. A number of communities in Ottawa have faced eviction from once affordable housing, including Heron Gate, Sandy Hill and Manor Village.

More than 12,000 households in Ottawa are on the waitlist for subsidized housing units, Ottawa ACORN says, with many waiting for years.

Whitzman, who calls herself a swing voter, lives in Ottawa Centre – a potential battleground riding after Liberal incumbent Catherine McKenna announced she won’t be running again this year.

“I suspect that in Ottawa Centre, the candidates are going to get a lot of questions about housing,” said Whitzman. “I certainly know that when the candidates come by my door, I’ll be asking them about housing.”

Vote Housing campaign

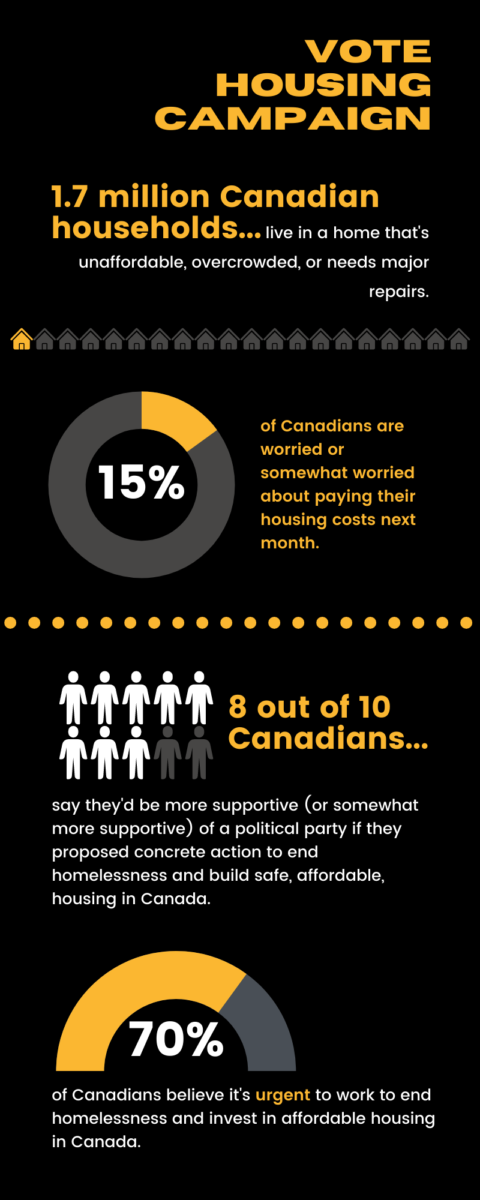

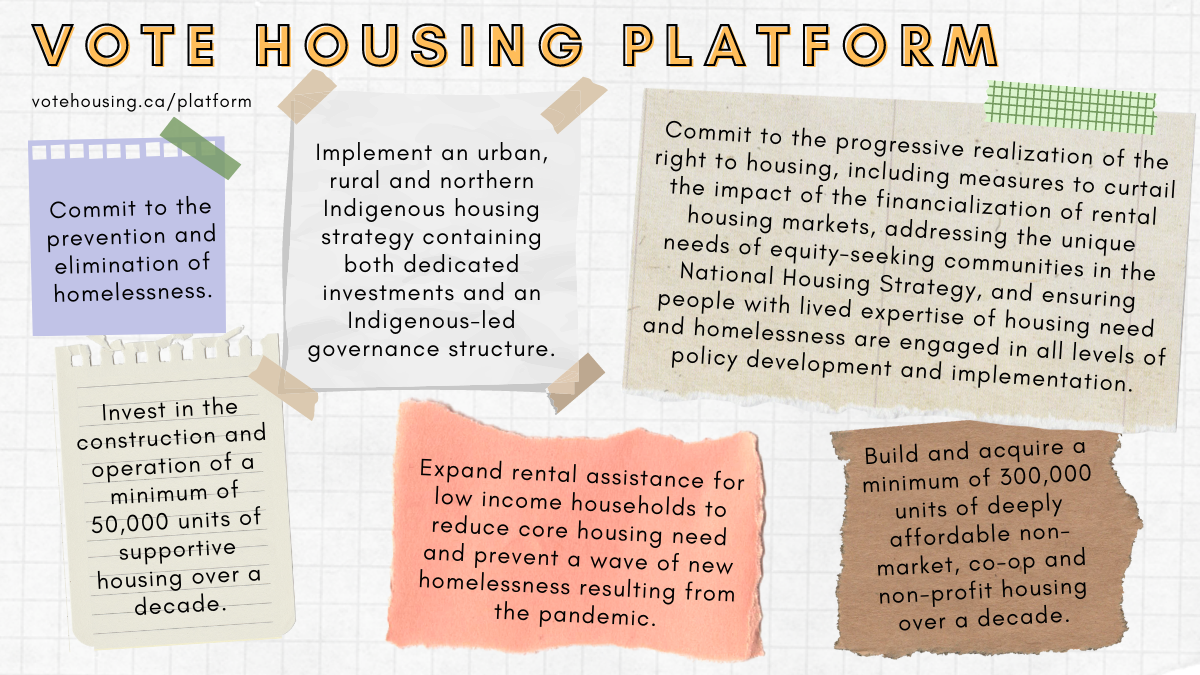

Whitzman is supporting Vote Housing, a national, non-partisan advocacy campaign that encourages voters to ensure parties recognize housing and homelessness as a key election issue. The campaign is led by a coalition of four organizations: Canadian Lived Experience Leadership Network (CLELN), the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, the Canadian Housing & Renewal Association, and the Co-operative Housing Federation of Canada (CHF Canada).

“Oftentimes politicians like to grab on to different wedge issues to divide Canadians,” said Tim Ross, executive director of CHF Canada. “Housing is clearly an issue that brings everybody together and all political parties need to support solutions to end homelessness and housing need in Canada.”

During the pandemic, rent continued to climb and vacancies went down, said Ross. Adding to the stress, most forms of rental regulation and legislation don’t guarantee the security of tenure.

“Even though we were in the middle of a pandemic, and millions of Canadians had lost their jobs, a real squeeze was put on the rental market,” he said.

Recent polling by Nanos Research for Vote Housing suggests one in three renters are worried about paying rent next month, compared to one in four this time last year. CMHC reported the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Ottawa rose 5.2 per cent in 2020.

Ottawa’s housing market was red-hot during the pandemic. In June, the Ottawa Real Estate Board reported the average price for a residential home in Ottawa had spiked to $736,241, a 35 per cent increase since 2020.

Federal policy needed

While most people understand problems in the housing market at the individual level, Ross said there are knowledge gaps about the housing system as a whole and about potential solutions. For example, not many people know about options other than renting or buying, like not-for-profit co-operatives and community housing, he said.

“We need to recognize that politicians, they don’t always lead, they follow. And they follow the numbers,” said Ross.

That’s why showing support for housing and homelessness issues is important, said Ross. The Nanos Research poll suggested 78 per cent of Canadians say they’d be more supportive or somewhat more supportive of a political party if it proposed concrete action to end homelessness and build safe, affordable housing.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the federal government made significant cuts to community and social housing, Ross said, which correlates to the number of individuals who’ve since experienced homelessness and housing need because of those cuts.

“Federal policy is really at the root of the mass homelessness and housing need experience that we have in this country today,” said Ross. “It’s going to take federal policy and concentrated investments to reverse the disastrous consequences of those policies.”

The federal government also directly influences action taken at the municipal government level, said Mathieu Samson-Savage, a Horizon Ottawa volunteer and PhD candidate in sociology at uOttawa.

“The federal election is a great time to talk about how the country can help cities address the issues,” he said – primarily through funding and regulation.

The City of Ottawa declared a state of emergency for housing and homelessness last year. Samson-Savage said he prefers the term “emergency” over words such as “crisis,” because it implies the need for immediate action, same as other emergencies like forest fires or floods.

“It is an emergency,” he said. “There’s thousands of people that are suffering. There’s thousands of people that are in unsafe conditions.”

The City of Ottawa defines affordable housing as housing for which low- or moderate-income households pay no more than 30 per cent of their annual income. According to the Rental Housing Index, 42 per cent of Ottawans pay 30 per cent or more of their income on housing. Additionally, nine per cent of renter households in Ottawa are living in overcrowded conditions.

The supply side

“The feds have always been the level of government that has the money to fund the building of housing,” said Burkholder Harris. “It’s really critical that they do that.”

While the supply of homes is important, it’s crucial to examine what kind of supply is being promised, Burkholder Harris said, as well as how affordability is defined. It’s also important to build environmentally friendly buildings, and ensure money is going to non-profits rather than private, luxury developers.

Voters should also consider how party platforms bring Indigenous communities into the housing conversation and position them as leaders, said Burkholder Harris. Nationally, 30 per cent of people experiencing homelessness identify as Indigenous, she said, noting money needs to be allocated for urban and rural Indigenous housing.

It is possible to end homelessness, said Burkholder Harris, and the solutions are tied to federal government leadership and investment in affordable housing.

“We really need to just put this as a priority for our country’s future. Because if we don’t, I think it contributes to significant amounts of inequity,” said Burkholder Harris. “We can do better than that. And it’s been done before.”