In the wake of a widely shared report on low levels of Holocaust awareness in the United States, there are growing calls across North America — including a parliamentary petition in Canada — for what many have been urgently seeking for years: comprehensive Holocaust education in schools.

Splashed across the home page of the Guardian news site on Sept. 16 was a startling headline that read: “Nearly two-thirds of U.S. young adults unaware 6M Jews killed in the Holocaust.”

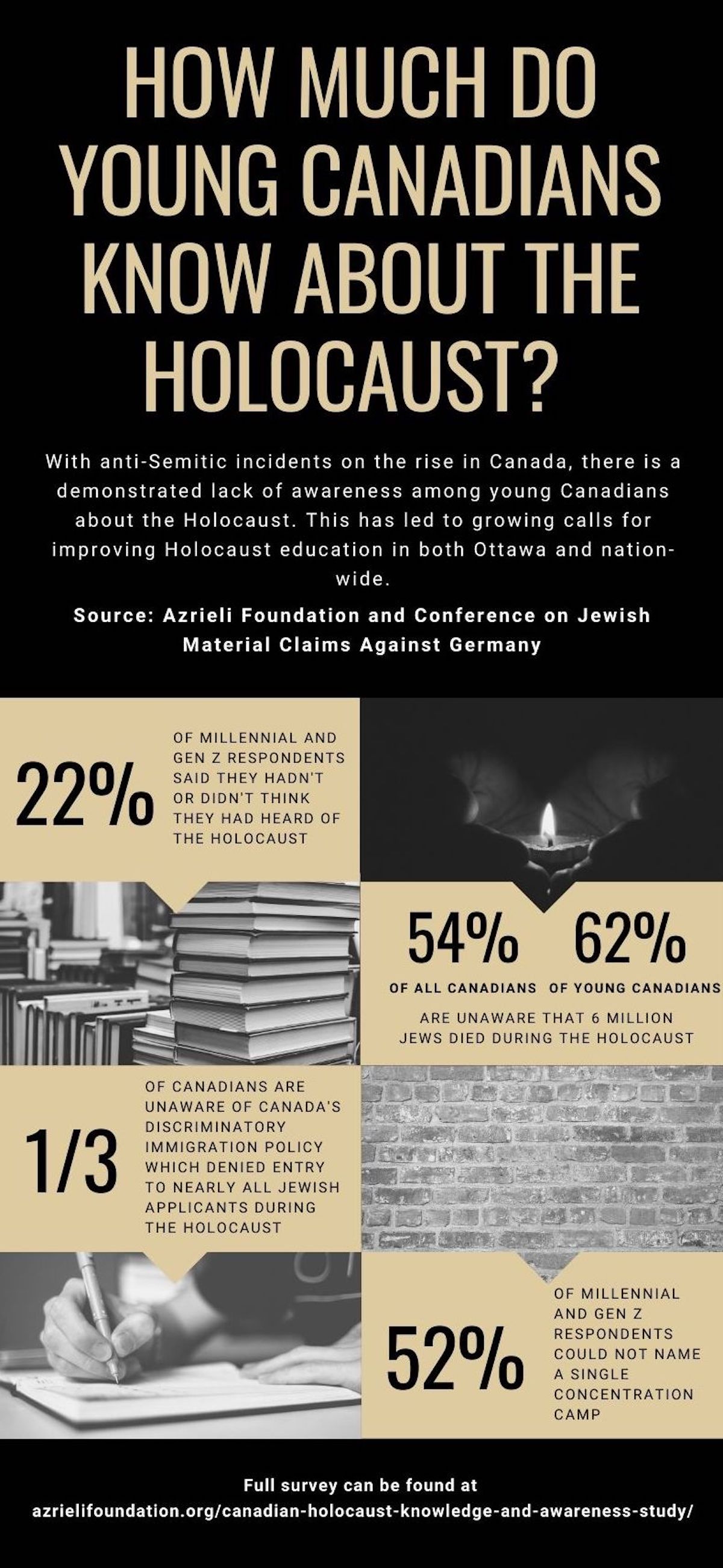

While the survey probed the Holocaust knowledge of American respondents, Canada is hardly immune to the phenomenon. A study commissioned by the Azrieli Foundation and the Claims Conference in 2018 found 22 per cent of Canadian Generation Z and Millennial respondents haven’t or don’t think they have heard of the Holocaust.

For those who work in Holocaust scholarship, that disturbing picture is one they’ve been trying to draw attention to for years.

While the curriculum for Ontario public secondary schools provides some mention of the Holocaust, it is often left to the discretion of schools and individual teachers to incorporate Holocaust education in the classroom, said Mina Cohn, the director of the Ottawa-based Centre for Holocaust Education and Scholarship (CHES).

“The Holocaust is taught in Grade 10 as part of World War II, with at best two classroom periods dedicated to the topic. However, the amount of time dedicated to the topic varies depending on the interest of the teacher,” said Cohn.

While the Holocaust may be touched on briefly in other courses, those brief lessons in Grade 10 history class is the extent of the mandatory Holocaust education high school students in Ontario will receive.

Those variables mean that for secondary students in Ontario, there is very little consistency in the programming they receive around Holocaust education, and it’s introduced quite late.

Encyclopedia Brittanica defines the Holocaust as “the systematic state-sponsored killing of six million Jewish men, women, and children and millions of others by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II.” However, Holocaust educators warn that even this bare bones summary is not as universally known as one would hope.

“A ‘typical’ high school student’s knowledge of the Holocaust varies tremendously, which points to the gaps in both teacher training and the age of instruction . . . We need to begin Holocaust education at a younger age and provide teachers with appropriate training,” said Melissa Mikel, the director of education at the Toronto-based Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Centre for Holocaust Studies.

Concerns about whether young Canadians are being adequately educated about the Holocaust have grown louder in recent years, particularly as anti-Semitic incidents continue on an upward trajectory.

As B’nai Brith, a Jewish advocacy organization, has reported, 2019 saw anti-Semitic incidents in Canada increase for the fourth consecutive year. Ontario had the greatest increase of any other province, with a 62.8-per-cent rise from 2018.

In fact, in July, CHES member Arthur Leader initiated a parliamentary petition calling on the federal government to improve and expand Holocaust education nation-wide. The online petition, which currently has 642 supporters, will continue to gather signatures until November.

The petition, sponsored by Anita Vandenbeld, the Liberal member of Parliament for Ottawa West—Nepean, makes specific mention of the need to better educate young Canadians.

Leader’s petition states that Holocaust education helps young Canadians “understand the dangers of indifference to the oppression of others,” while noting that as time passes, fewer Holocaust survivors are able to share with us their accounts, and fewer young people are aware of the atrocities committed.

Leader also makes note of the importance of Holocaust education in combating Holocaust deniers, who have found a platform and an audience in the digital age — an audience that could include impressionable young Canadians.

However, even when individual educators incorporate more Holocaust education into their classrooms, it can be challenging.

Mikel notes that because most teachers are not required to provide instruction about the Holocaust, it is not included in their training.

“Unless teachers seek out training from organizations like ours, there is no standardized training to prepare teachers for this topic,” said Mikel.

“The Holocaust is a very broad topic, and most teachers lack knowledge and do not know how to deal with the subject,” added Cohn. “A new revised core provincial curriculum that mandates teaching the Holocaust, which includes best practices by Holocaust educators across Ontario, is needed.”

Cohn and Mikel encourage teachers to make use of the resources available to them. The Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Centre has a best practices guide for Holocaust education available, and CHES hosts an annual teachers’ workshop to help train educators within Ottawa.

The Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, for its part, says it is “committed to ensuring students understand and appreciate the significance of the Holocaust.” OCDSB schools will host Holocaust survivors for students to hear from, and the board has also partnered with organizations such as the Simon Wiesenthal Centre.

However, with the Ontario curriculum as the guiding framework, Ontario school boards are left largely to devise their own plan about when and how Holocaust education is introduced.

The consequences of inadequate Holocaust education, Mikel warns, are serious.

“Many children are told that Hitler was crazy, or evil, and learn nothing about the widespread popularity of Nazism, or Europe’s long history of anti-Jewish violence . . . We need to equip young people with the tools to think critically about our past if we want them to be engaged citizens in the present.”

For Cohn, Holocaust education goes well beyond remembrance, presenting students with questions about morality and human behaviour that still echo today, as well as developing social awareness, empathy, critical thinking and moral reasoning.

“Many people don’t understand that conversations around human rights today were born out of the ashes of the Holocaust,” said Mikel, “acknowledging that the post-war reckoning with the genocidal policies of the Nazi regime has radically altered the way we think, discuss, and legislate human rights issues.”

Dear Readers,

Very good comprehensive article.

I think what our todays’ students need these days is a number of new methods to teach the Holocaust subject.

The student of today is no longer the one when Holocaust Education entered the History subject in early 1980,

The highly tech. has of course its advantages but also its disadvantages.

We must expand the subject as per the students interests and ability to understand, too many years have gone by and it has been proved that History is one of the hardest subjects for students to comprehend, they just can relate the most to the last 10 years, and we are asking for 80 + years ago.

I would like to recommend that we teach the Holocaust through and only through the Arts and Culture.

Our Foundation in Romania is teaching the subject which only has started since 2004 when Romania recognized having a Holocaust .

Not just Culture and Arts but with great emphasis on the “Life before the Holocaust”, which is so important in order to understand what has been lost.

It seems the issue of speaking and listening to survivors has been somehow worked out technologically by the Shoah Foundation.

Now it’s the curriculum.

Sincerely

Peninah Zilberman former Director of the Holocaust Educational Center in Toronto

Our children are not learning about the world wars and the holocaust. This lack of education can lead to racism and the repeat of history. I firmly believe that entire courses should be taught about the war, Nazism and the holocaust. I’m 65 years old and if I had not taken an interest in history I would not have known the atrocities that happened in WWII. My lack of knowledge was embarrassing. It needs to change. And I’d like to be part of that change.

Hi James – I appreciate your comment to this article and wanting to be part of the change. My mother survived the Holocaust concentration camps including Auschwitz and my father survived the Nagasaki atomic bomb as a POW in Japan. I wrote a book and give school presentations to tell their amazing story of survival, love and triumph over tragedy to young people. I tell the story not just to teach kids about the history and what this kind of hate, evil and discrimination my parents experienced can lead to if we don’t stop it, but also for them to learn about resiliency, empathy, compassion, tolerance, self-worth and the importance of purpose, and so much more that helped my parents to survive and persevere in the face of their hardships and suffering. I invite you to visit my website at http://www.RoslynFranken.com/youths.html and learn more. You can help by learning about the work I am doing and sharing with others about what I am doing so that I can reach more kids. If you know anyone in the school systems in your area, please spread the word. There are videos on that page so you can see and hear testimonials from students, teachers and school administrators as to the positive impact my story has on students’ attitudes and how it is teaching them and helping them change their perspectives. If you look me up on Google and Youtube you will see much more as well.

Canadian History curriculum needs to include this WW2 information.

When I taught history, Canadians were the best informed on our legacy in World history.

Canadians need to appreciate our own ancestors, Indigenous, Jewish, European,Black and any new Canadians. Bias can be blamed on education. It’s not up to journalists!

My mother survived the Holocaust concentration camps including Auschwitz and my father survived the Nagasaki atomic bomb as a POW in Japan. I wrote a book and give school presentations to tell their story of survival, love and triumph over tragedy to young people. I tell the story not just to teach kids about the history of the Holocaust and WWII and what this kind of hate, evil and discrimination my parents experienced can lead to if we don’t stop it, but also for them to learn about resiliency, empathy, compassion, tolerance, self-worth and the importance of purpose, and so much more that helped my parents to survive and persevere in the face of their hardships and suffering. In these times of growing division and adversity, and increasing rates of teen depression and suicide, I truly believe that youths everywhere need to know my parents’ amazing survival over suffering, humanity over hate, and triumph over tragedy, NOW more than ever. The lessons from the Holocaust and WWII are powerful if only we choose to learn them and learn from them!!! For more information, http://www.RoslynFranken.com/youths.html