The National Capital Commission’s decision to create a national monument to commemorate decades of government-sponsored discrimination against LGBT people in Canada is receiving mixed reactions from the community.

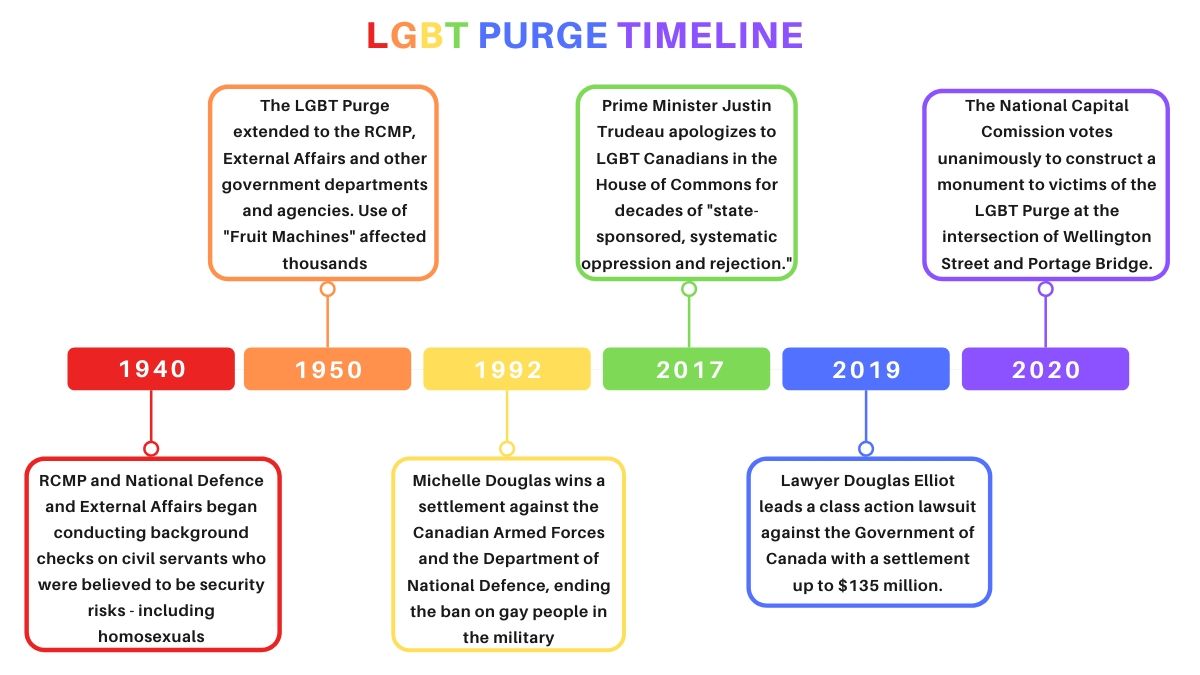

The $8-million monument will, in part, be a visible reminder of what is known as the LGBT Purge which began during the Cold War and continued until the mid-1990s.

Thousands of federal public servants, members of the RCMP and the Canadian military were forced to resign because of their sexuality.

The monument will be located at the intersection of the Portage Bridge and Wellington Street, just west of Library and Archives Canada.

“The site selected reflects the prominence of a national monument of this importance,” Tobi Nussbaum, the NCC’s chief executive officer, said in a press release regarding the new monument.

While many consider it important to draw attention to this dark time in Canadian history, some also see the monument as part of a “politics of apology.”

Patrizia Gentile, an associate professor at Carleton University whose research has focused on the purge and national security issues in the Cold War, is ambivalent.

“I’m not sure we’re actually contextualizing it in a larger history of trauma,” she says.

Gentile, who identifies as queer, says she feels conflicted about the government funding a monument to show it believes in the human rights of LGBT individuals when “there are other ways in which the state has also traumatized populations and marginalized voices in our country.”

Carling Miller, the executive director of Kind Space, an LGBT community hub and service centre in Centretown, agrees.

“I think monuments can give a false impression that things that happened are no longer happening,” she says.

Miller, who is Black and a lesbian, says queer and trans oppression continues today in less overt ways.

Surviving the Purge

For purge survivors like 56-year old Ottawa-born Michelle Douglas, however, the planned monument is a “means to memorialize the purge and those who experienced it.”

Douglas had only just begun a promising career with the RCMP in 1986 when she was lured to a Toronto hotel by a superior and interrogated for two days about her sexuality. It was later, when she was flown to Ottawa and strapped to a polygraph machine, that she admitted she is a lesbian.

In 1989, she was fired for being “not advantageously employable due to homosexuality.”

“I was traumatized, I was deeply alone,” she says.

She went on to sue the government for discrimination and, on Oct. 27, 1992, the Canadian military settled for $100,000 and the Federal Court of Canada ruled that LGBT men and women could not be banned from joining the military.

Douglas, who is now the executive director of the LGBT Purge Fund, says she wants Canadians to reflect on how for years, the federal government treated many of its employees “brutally, in a way that would shock most Canadians.”

The purge of LGBTQ individuals in the Cold War era

During the Cold War, LGBTQ individuals were seen as having a “character weakness,” and therefore susceptible to blackmail by the Soviet Union.

“The idea that homosexuals are not part of the reproductive process of creating the next set of citizenships to make a healthy, strong nation with a good economy made them enemies,” says Gentile.

She says the government, along with the RCMP, “orchestrated a systemic vetting and purging program” to ensure gay men and lesbians would be removed from the government or the military.

The RCMP bugged the phones of officers and broke into their homes. Staff were photographed and followed to catch homosexual activity.

Included in the national campaign was a special project known as the “fruit machine,” developed by Frank Robert Wake, a Carleton University psychology professor.

Gentile says the machine was, in fact, a series of psychological tests designed to measure peoples’ heart rates, pulses, sweat glands and pupil sizes “as a way to detect homosexuality.”

One of the many tests included having people sit in a dark room and flashing nude pictures of both sexes, where a pupil-dilated reaction to a same-sex photo would supposedly confirm homosexuality.

How times have changed

According to Cpl. Elenore Sturko, a media relations officer with the Surrey RCMP, things have since changed in Canadian society and within the organization.

Sturko, a lesbian, says she feels well-supported in the workplace. She adds she is the beneficiary of the work done by LGBT activists who pushed for cultural change in Canada.

“I’m not judged for who I am as a person in terms of my sexuality, but on the merits of my willingness to provide service and the service that I provide and being a member of the RCMP,” Sturko says.

Sturko is the great-niece of Dave Van Norman, an RCMP sergeant who was fired in the 1960s for being gay.

She says the planned monument is a way to memorialize people like her uncle who did not live to claim compensation from the government or hear the prime minister’s apology three years ago.

“It is our collective shame that you were so mistreated. And it is our collective shame that this apology took so long – many who suffered are no longer alive to hear these words,” Trudeau delivered a historic apology to the House of Commons in 2017, “And for that, we are truly sorry.”

Sturko, however, says though her uncle left his career “in scandal”, she wants him to be celebrated “because he was ahead of his time in terms of community policing and great service.”

The monument is being paid for as part of a class-action lawsuit that was settled in 2017 for more than $100 million. Up to $25 million of the settlement amount is earmarked for special projects led by the LGBT Purge Fund corporation.

Along with the settlement, 718 RCMP, Armed Forces and public servants filed for compensation of between $5,000 and $175,000. Payouts will be decided on a case-by-case basis.

“If we have these millions, right, I’d rather the state actually use it to help people in their everyday lives,” Gentile says.

She says she would like to see the government fund education programs to stop the suicide of trans and queer homeless youth, for example.

“I want to know what you’re going to do to help people in their everyday life, because I’m fine,” she continues, “but there are people that are not.”

“The monument is just one part of . . . sort of the tip of the iceberg,” Gentile says.

The design competition for the monument is set to begin in the spring.