Like many young Canadians, Connor Merzetti and Ikue Mori are conscious about climate change and the carbon footprint of suburbs associated with a higher dependence on vehicles.

But raising a family in a big city like Toronto is becoming unattainable for the young family. High real-estate prices and the lack of accessible green spaces are driving them to suburbia.

“I’ve always said that Toronto is a wonderful place to live if you’re rich,” says Merzetti referring to neighbourhoods that have houses with big yards.

Affordable apartments or condos do not often offer the green space Merzetti and Mori want for their children.

“There’s no green space at all. When parents take their kids outside to play, they’re playing in an alleyway by the dumpster, literally. Or there’s a tiny patch of grass that’s basically a dog toilet, which is where the kids play,” says Merzetti, who works as a concierge at a downtown condo.

Such conditions in Canada’s big cities are pushing many people towards suburbs.

According to a report from Statistics Canada, urban areas like Montreal and Toronto saw a record number of people from July 2019 to July 2020 leave for suburbs, small towns or rural areas.

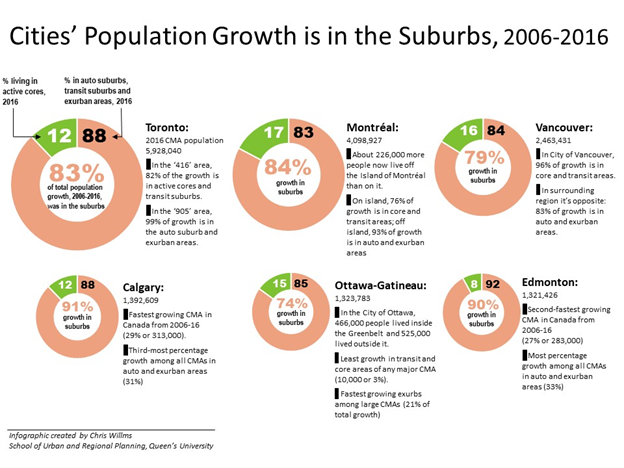

A study by the Council for Canadian Urbanism, based on data from 2006-2016, shows that 80 per cent of residents in large metropolitan regions such as Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa-Gatineau live in the suburbs. There is five times as much population growth in suburban areas compared to the downtown cores.

Responding to the demand, cities are expanding, often at the cost of higher carbon emissions and lost biodiversity.

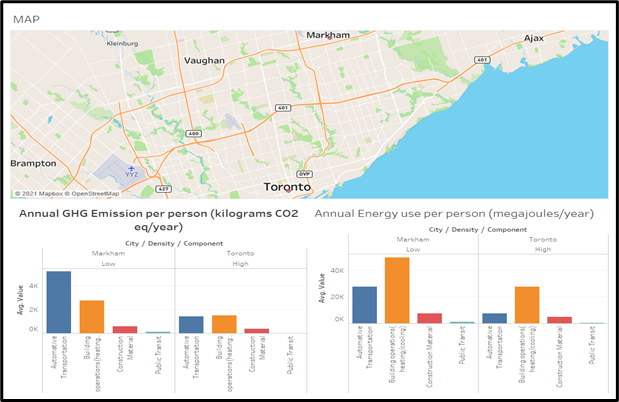

A 2006 American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) study comparing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in downtown Toronto with a suburb in Markham shows that low-density suburban development is more GHG intensive than high-density urban core development by a factor of 2-2.5 per person.

Transportation GHG emissions and energy use is found to be 3.7 times higher in the suburbs because of higher car dependency, according to the ASCE study.

Some researchers and experts argue that greener solutions for mature cities and new suburbs are possible. Sustainable choices can be made to reduce carbon emissions, protect biodiversity and make cities greener and more livable.

But there are many challenges to overcome.

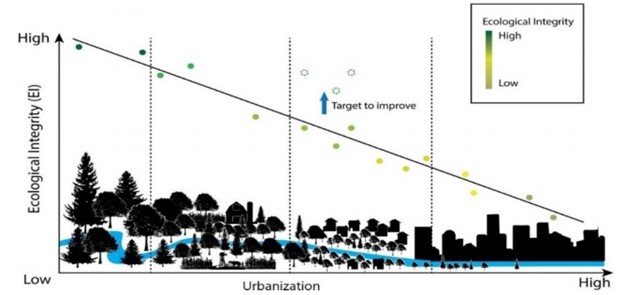

“Urbanization, undoubtedly, has negative consequences for biodiversity,” says Marc Cadotte, a professor of biological sciences at University of Toronto.

As cities grow, there is a loss of habitat, he says. The number of animal and plant species decrease which can increase the risk of extinction.

“As animals and plants are faced with increasing environmental stressors like noise pollution, light pollution, air pollution, water pollution, and interactions with vehicles … we see a decline in species that can’t deal with the stressors,” he says.

The 2019 Toronto Biodiversity Strategy report showed that ecosystems have the highest ecological integrity when they are not disturbed by these human activities.

“‘Ecological integrity’ is a framework used to describe an ecosystem that is ‘whole, intact or unimpaired,’” the strategy writers state.

In addition to the loss of diverse ecosystems, one of the biggest environmental impacts of urban expansion is the release of carbon from transportation.

“More sprawl means people must travel further – often by car – to get to jobs and basic amenities,” writes Cheryl Randall, Ecology Ottawa’s campaign organizer, in an email.

Transportation is the largest source of GHG emissions, accounting for 37 per cent of Ontario’s GHG emissions, according to the 2016 Ontario Climate Action Plan.

“Instead, walkable communities see the lowest levels of emissions,” writes Randall.

Urban planners often refer to walkable communities as ‘15-minute cities’, developments that have a mix of residential and commercial areas so that residents can access basic necessities within their own neighbourhoods on foot.

“The 15-minute city is more relevant than ever as an organizing principle for urban development. … It will help to reduce unnecessary travel across cities, provide more public space, inject life into local high streets, strengthen a sense of community, promote health and wellbeing, boost resilience to health and climate shocks, and improve cities’ sustainability and liveability,” Randall states.

Yuill Herbert, the director and founder of Sustainability Solutions Group, a worker’s co-operative in Canada that supports municipalities in identifying strategies to decarbonize communities, agrees that to minimize the environmental impacts of sprawl, communities need to ensure, “whatever new construction happens enables people to walk or cycle or take transit to a wide basket of destinations including schools, stores, healthcare, workplaces and so forth, so that they’re not reliant on vehicles for travel.”

Herbert says, “the preferred approach is to intensify development within downtown cores in a way that’s livable. That means not necessarily skyscrapers or tall buildings, but low-rise buildings that have a high density and allow people access to the streetscape easily.”

Benjamin Gianni, a professor of urbanism at Carleton University, says a higher population density, meaning more people living per square kilometre, is better for the environment.

Traditionally, he says, suburbs are designed so there is a lot of private space and no public space. Every house sits in the middle of a big yard.

“In a greener suburb, you would attempt to build houses on smaller lots or build attached housing and aggregate that green space into a common green space, like a park or a green corridor that can run through the suburb and connect it to other green corridors as well,” he says.

Retaining parks, greenspace, and habitat corridors are vital to reducing the environmental impact of urbanization.

“For areas that are heavily urbanized, there are a number of creative ways to introduce green and to make them a little bit more sustainable. For example, ensuring there are a lot of street trees that can help reduce temperatures and provide habitat and food for birds and insects.”

Marc Cadotte, ecologist

Ecologist Marc Cadotte says growing cities need to “ensure they’re setting aside relatively large and interconnected green areas, which have a multitude of benefits. People enjoy them for recreation, people enjoy looking at them, but they’re really valuable for biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.”

“For areas that are heavily urbanized,” he says, “there are a number of creative ways to introduce green and to make them a little bit more sustainable. For example, ensuring there are a lot of street trees that can help reduce temperatures and provide habitat and food for birds and insects.”

Cities can also offer opportunities for some species. For example, Cadotte says we often see higher bee diversity in cities.

The main issue with planning a sustainable, green city, is that developments often have already been approved, without considering future environmental factors.

Herbert says it’s difficult to access sustainable solutions right now, “because so much development is already locked in.”

“People have bought land with the intention of developing it into subdivisions or neighbourhoods 10 years ago. It’s very hard for a city to just pivot quickly and change the nature of the type of built environment that it’s supporting.,” he says.

Cadotte agrees that as cities grow, “they often have a mindset from a couple decades ago about what a city should look like instead of really thinking ahead and being innovative and thinking about, ‘what do we want that city to look like in 30 to 50 years?’”

“What we’re stuck doing is having to go back on previously urbanized areas and figure out ways to regreen them and make them more environmentally friendly and sustainable, when today we should be doing that in a more concerted way,” he says.

Gianni says, “I think the city has to grow in both directions, it has to grow up, and it has to grow out.” But he says cities have to establish growth boundaries.

“Walkable communities see the lowest levels of emissions.”

Cheryl Randall, Ecology Ottawa

Last summer, the city of Ottawa expanded its urban boundary. Many municipalities are following suit, as the provincial government has minimum requirements for residential development.

“When the vote to expand the urban boundary passed last summer, many of us were deeply disappointed, but we started to shift the focus to positivity – what we want to see the city to become, rather than what we were angry about and unhappy about, and show how it can be done, how our dream city is actually achievable,” writes Cheryl Randall.

A green, sustainable community in a high-density city could encourage couples such as Merzetti and Moori to stay within the urban core.

Merzetti says, “If there were some condos and some townhouses as part of one project, if they had a community center, a pool, a game room for kids to play, a park, amenities like that, it could work.”